The first time I had a pregnancy scare was shortly before 2020, when I was in my early 20s. I googled how to access plan B and was surprised and relieved at how easy the process was. I felt some resentment too: I shouldn’t have been surprised. That was what feminists and activists before me had fought for. Easy and affordable access to reproductive care.

I entered the details required to place the order, and within minutes I received a cancellation notification on my phone. Assuming an error, I tried again; the money was still pending on my card. It was canceled for a second time.

Related: The Supreme Court’s new attack on the right to privacy was planned for 50 years

I called my best friend, asking to borrow money to buy some medication. At that point, almost 24 hours had passed, and I knew I would have to wait the following day to head to the pharmacy. After the third order was canceled, I started panicking. I knew the chances of being pregnant were low, given my medical history, but the thought of needing an abortion was scary. I knew I could access it fairly easily, should I need to. I knew my partner would come with me, and be supportive. I knew my best friend could drive me there.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

I finally got an email from the pharmacy, explaining why the orders had been canceled: “We cannot sell plan B to men, please ask your partner to order her medication directly.”

Needless to say, my partner in this case had no use for plan B. Nor could they have ordered it on my behalf.

I didn’t expect similar feelings – the same pain, fear, frustration – to emerge again recently, even more violently. My partner – transgender as well – was lying next to me in bed, browsing social media, when they suddenly stopped and looked at me.

“They’re overturning Roe.” was all they said. It took me a moment to understand what they meant. Even longer to understand what that would mean in the upcoming days. Once again, I felt my body paralyzed with horror.

But I still had to look it up myself, so I started reading tweets, articles, and news – all the “No uterus, no opinion,” “Stand with women,” and “Protect women’s health” slogans.

It’s hard to describe the pain of feeling excluded by a problem that’s still affecting you.

There is a fine line between combating erasure and being worried your experience will be used to distract from that problem. As a trans man, I need access to abortion and contraception, whether they’re labeled for women or not. But erasure runs deeper than semantics, and it’s rarely accidental.

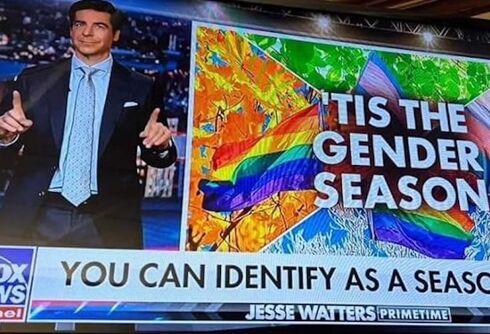

Following the Roe v. Wade leak, a great part of the debate has shifted to the language used when discussing abortion. Part of it is aimed at including trans men and non-binary people who might have a uterus, engage in penetrative sex, don’t have access to contraception, or have to terminate wanted pregnancies for health reasons. The connection between reproductive rights and equal rights for the LGBTQ community has always been clear, both from community involvement and legislation, but we’re only just starting to see the harm of describing abortion as a women’s rights issue.

Overturning Roe v. Wade is not just a women’s issue. Framing it as such not only erases transgender and non-binary people who might need access to it, but also fails to recognize the threat it poses to body autonomy. It creates a concerning precedent by restricting agency in healthcare by targeting specific minorities.

Personal interest in this conversation shouldn’t be the leading argument: there are women (cisgender and transgender) who cannot get pregnant who are still pro-choice; there are disabled people who have been advocating for body autonomy since before Roe v. Wade was introduced; there are BIPOC who have historically faced violence and reproductive health disparities.

Statements like California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) asserting “if men could get pregnant, this wouldn’t even be a conversation” don’t just exclude transgender men, but imply that those solutions would automatically be accessible and inclusive. But legislation about reproductive rights is often far from it: weight, race, class, and religion affect access even when those services are available.

Inclusion led exclusively by lived experience and personal motivators will rarely translate to equity because the demographics historically excluded will rarely reach positions of power. Human rights rely on the majority recognizing them as such, and in this scenario, the reason why language is fundamental is to make sure it reflects the number of people affected.

Newsom went on to add, “This decision isn’t about strengthening families – it’s about extremism. It’s about control.”

When looking at the context of the recent proposals, the bigger picture is much more complex.

Missouri’s trigger law might ban IUDs and plan B, Arizona GOP candidate Blake Masters is pushing to overturn Griswold v. Connecticut banning contraception including condoms, Idaho House State Affairs Committee Chairman Brent Crane will be holding hearings to ban emergency contraception, abortion pills, and potentially IUDs.

Abortion in this scenario is not the end goal, it’s following a trend of progressively preventing equal access to healthcare.

Gallup reports that one in four Americans – both in 2016 and 2020 – would only vote for a candidate that shared their view on abortion. Nearly half of voters (49% in 2016 and 47% in 2020) considered abortion one of the most important factors when voting.

But by definition, abortion cannot be a “single issue.” It doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it’s intrinsically related to other human rights and forms of discrimination. Part of the reason rights like these are being rolled back and are under attack is because people do not see them as related: “women’s rights” are seen as a separate category, “trans rights” are seen as only related to trans people, and “disability justice” is seen as related only to disabled people and people with disabilities. But collectively, they are stepping stones in what is a global attack on human rights and access to healthcare.

Treating them as separate fights divides voters, and isolates those who need support on specific issues. Women are more likely to respond to threats to ban abortion, trans people are more likely to respond to transphobia, and fostering hypercriticality and conflict between demographics prevents them from realizing they’re fighting towards the same goal.

Everyone, regardless of whether they have a uterus or not, deserves to make informed and intentional choices about their bodies and to receive adequate support towards the intended outcome.

So is overturning Roe v. Wade a women’s rights issue? Yes. And a disability issue. A race issue. A trans rights issue. Any policy that prevents autonomy and access to healthcare is violent and predatory and should be addressed as the human rights violation it is.

What happens when a transgender man needs Plan B?