Excerpted from Bilha Fish’s Invincible Women: Conversations with 21 Inspiring and Successful American Immigrants, publishing May 14, 2020 by Hybrid Global Publishing.

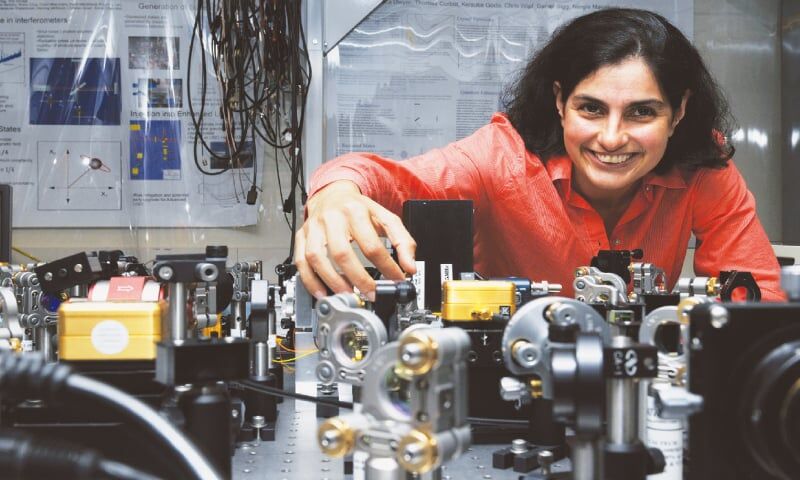

It takes ten minutes to convince Nergis Mavalvala that she would be an asset to my book. I make my case by pointing out that she has successfully challenged many stereotypes: being a woman astrophysicist in a predominantly man’s world; an immigrant academician; a self-described “out, queer, person of color”; and to top it all, a working mother of two children. But once she is persuaded, her exuberant personality takes over and reveals to me the infinite vastness of her own life as well as the mysterious skies she studies.

Related: This inspiring trans woman went back to her boys high school to train them on LGBTQ issues

Nergis was born in Karachi, Pakistan, to a family that encouraged and supported curiosity, knowledge, and education. She believed that the best learning occurred outside of the classroom, and hers began at the neighborhood bike shop and local electrician where she first discovered and explored the ways gears and circuits work.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

She continued to develop her interests and practical skills, exploring machinery and electronic circuitry and building a laser, which eventually led her to join Dr. Rainer Weiss’ team at MIT in 1991, working on the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). (Weiss won the Nobel Prize in physics in 2017 for his and his team’s work on the LIGO.) LIGO detects the effects of gravitational waves on precisely aligned mirrors that reflect laser beams, a new method to discover events that happened millions to billions of light years away in space. In the hopes of building a more sensitive LIGO to detect fainter and farther gravitational waves, Nergis has explored the fields of quantum optics and optomechanics. Her work could lead to solving the mystery of the Big Bang, thus combining her lifelong love of construction and physics, a love that flowered and was nurtured back in that bike shop in Karachi.

Nergis’ relaxed philosophy about being an outsider culturally and professionally—a Pakistani immigrant and one of very few female physicists—in some ways also made it comfortable to reveal her sexual identity. When she fell in love, she says it was an organic process of coming out. And in retrospect, she sees her tomboyish behavior during childhood as a gender-bending process in the making. By being herself, she has become a role model, receiving the MacArthur “Genius” Award in 2010.

Do you believe that your research will lead to detecting the faintest gravitational waves that have been created by the Big Bang?

Ah, yes. That would be something. I don’t think that will happen in my lifetime. I think it’s possible to do, and it will be done in the generations to come, but such faint waves require more sensitive instruments. Going back to Galileo, his first telescope was such a small thing that even some toy telescopes today are better.

But it’s been four hundred years since then, and we have built incredibly bigger and more powerful telescopes. And that has allowed us to see farther and farther. What Galileo saw was in our own solar system. He saw craters on the moon, he saw Venus, he saw Saturn. Our light telescopes are looking out to the edge of the observable universe.

And so that’s the next thing that has to happen in this field in gravitational waves. You have to make more and more sensitive instruments. At times it means bigger, at times it just means cleverer, and sometimes it means both.

Would it require longer laser paths and observatories in space?

Yeah, there is the idea of putting them in space, so it’s within human reach to observe gravitational waves from the very early universe.

Well, that would be amazing because it might cause a controversy with religious beliefs.

Will it cause any more than there already is? Just because we saw gravitational waves that take us back to literally the very beginning doesn’t mean we’ll have an explanation for how the very beginning happened. Well, I don’t think it will help the controversy if there is any. It will just give us more information that the Big Bang either happened the way we thought, or maybe there will be a surprise and it didn’t happen the way we thought. And what caused the Big Bang?

Which means that you needed both creation and evolution to get to where we are.

I think that would be nothing new added to that debate.

There’s some important social issues that I would like to talk about. Did you face difficulties trying to achieve in science in a man’s world?

Personally, no. Do I think or observe that there is systemic bias out there? Yes, it’s out there. My own personal experience has been very positive, and I think it’s in part because I’ve had amazing mentors who don’t mentor me because I’m a woman—they mentor me because I’m a scientist.

But that doesn’t for a moment mean that I’m not aware that there are structural factors and bias out there that keep certain demographic groups out. But it hasn’t been my experience.

What about being an immigrant? Did you find yourself different? Did you have difficulty adjusting? Think about when you came to this country. Because once you became famous and appreciated, the world was yours.

That’s a good question. When I came to college, I came to an environment that was pretty welcoming. Certainly, I’ve had experiences of the same kind that others have had of being exoticized: “Oh, you’re from Pakistan, you must be somehow an exotic creature.”

I think if anything, it made me more determined. I wouldn’t even say they were negative experiences; they were more experiences where I encountered people who just didn’t know much about the rest of the world. So they had funny questions or funny expectations. I, on the other hand, even growing up in Pakistan, had much more awareness of what the rest of the world was like.

I’m the kind of person who just blows through all of that stuff. I don’t notice it; I just keep going. I also did not have any culture shock, because I grew up reading English and American books and watching English and American television. I certainly didn’t find anything unexpected.

What about being openly gay? Was it easier to deal with in the United States?

Yes, I think it’s part of the milieu that I moved in. I first recognized for myself and acknowledged to the world that I was gay when I was a graduate student at MIT, and it kind of came pretty naturally, being in the US and not one to feel too bound by existing social norms.

I was in my early- to mid-twenties when I came out. No one seemed to care or notice. I think the hardest part of it might have been working through it with my family, but certainly not in the workplace. If people thought anything of it, they had the good sense to not say anything.

In one way I believe that discovering you’re gay later in life saved you from the heartache of confronting this knowledge as a child.

Yes and no. When I look at young people today coming out as queer, for many, especially in the cities where I live, it’s often a very natural, very supported process. I know that’s not true all over the country, though.

You’re strong and confident—knowing who you are, what you’re all about. And that translates to the ability to adjust.

I think strength and confidence are correct because that’s what you need to just glide through it.