It’s summer 1978, and 12-year-old Jonathan Adler, sporting a Rush concert T-shirt, hovers over a potter’s wheel for the first time.

As he molds the wet clay, the centrifugal force transforms the lump into a roughly thrown vase. It’s at this moment that Adler discovers the power of the creative process, setting in motion a career trajectory that will reimagine modern-day ceramics and redefine the design industry.

Forty-five years later, Adler has become one of America’s most influential and innovative product designers and is celebrating a milestone anniversary of his brand, which encompasses hundreds of items — from pottery and décor to furniture, lighting, bedding, and bath accessories.

What began as a young potter’s obsession with 20th-century designers such as Chanel evolved into a global company with 10 retail locations, including a new SoHo atelier, pottery workshop (including a 2,000-pound kiln), and design studio, which brims with prototypes of Adler’s constantly evolving collections. In 2022, Adler’s revenue neared $100 million.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

“As much as I am an innovator, it has to do with being an insular outsider,” Adler told LGBTQ Nation. “I felt an urgent need to say whatever I needed to say. I think a lot of young creatives start making stuff — whether it’s music or whatever — because they have something they’re desperate to say. That certainly applies to me. When you’re an outsider with something to say, it’s probably unusual and perhaps, therefore, innovative.”

Adler, whose namesake company is commemorating its 30th anniversary, is among a wave of modern designers, including Nate Berkus, Bobby Berk, Cliff Fong, and Shavonda Gardner, who have harnessed their queer aesthetics to break into an interior design services industry valued at $12.3 billion in the U.S. Such innovation has also been recognized as a valuable part of STEAM — science, technology, engineering, art, and math — in which creativity and design principles become integrated disciplines for personal and professional development.

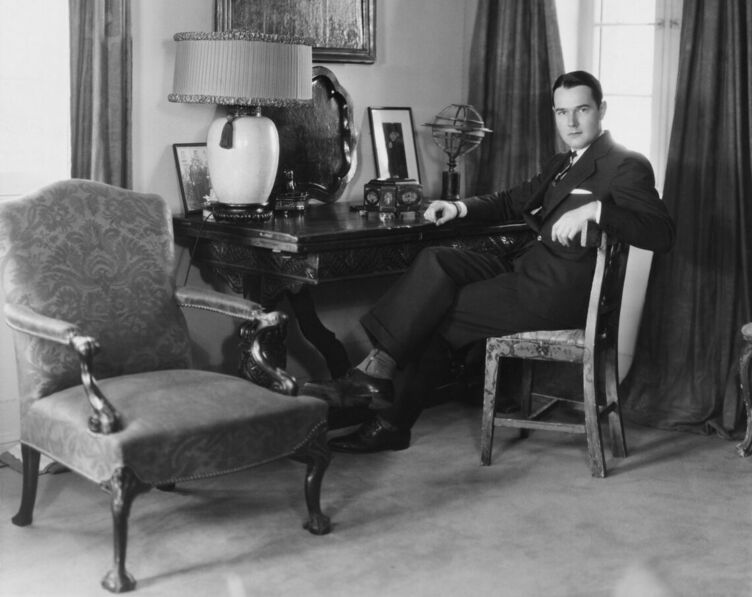

Historically, interior designers, decorators, and applied artists tended to be society women such as Elsie de Wolfe and Dorothy Draper, who traveled in distinguished social circles. Former Hollywood actor William Haines cracked the mold, leveraging friendships with silent film star Gloria Swanson and Academy Award-winning actress Joan Crawford (Mildred Pierce) to break into the insular industry. Haines also built a lifelong personal and professional relationship with Jimmie Shields, establishing themselves as one of Hollywood’s first openly gay couples (They remained together until Haines’s passing in 1973.)

For Adler, the desire to turn his creative passion into a design profession was put to the test when an instructor dissatisfied with his progress at Rhode Island School of Design told him he “had no talent” and should pursue a law career. Adler says it’s “the best advice I never took” and that “every creative person needs a naysayer to rebel against.”

After several years completing mundane tasks such as answering phones and faxing as an assistant in the film industry, Adler eventually returned to the potter’s wheel, continuing to innovate a unique combination of wheel-throwing, molding, and hand-building techniques

In 1994, his work caught the eye of buyers at Barneys through an introduction by friends James and Joanna Grace, whose table linen brand VanderPool & McCoy had achieved notoriety. Interest from industry leaders such as Todd Oldham and Carlos Falchi followed. Today, Adler’s pottery collections — from Muse’s surrealist body parts and animal-inspired Menagerie to the geometric Palm Springs black stoneware — are so ubiquitous they seem part of the design landscape.

Adler realized he’d need to think big in order to grow his business. In 1997, he partnered with Aid to Artisans, a nonprofit organization that connects designers with artisans in developing countries, and it was here that he also discovered a love for textiles. Commercial projects like the Parker Palm Springs hotel, a series of books including My Prescription for Anti-Depressive Living, and a stint as toy company Fisher-Price’s creative director followed.

All the while, Adler has continued to work with materials like ceramic tile, travertine stone, and washable textiles in innovative ways. He’s also influencing the next generation of designers.

HGTV’s Design Star: Next Gen winner Carmeon Hamilton brought a full-circle moment for Adler, who, as a series judge, suggested she cut back on her use of plants.

“I had to tell him no matter what, whether in the competition or not, plants would be an integral part of my designs as a way to honor my mother, who had passed,” Hamilton told LGBTQ Nation by phone from her Memphis-based design studio. Unknowingly, Adler had become the naysayer he once encountered, but Hamilton said she also holds profound respect for Adler, whom she described as “incredibly kind” and an ”industry pioneer.”

When asked what she believes has fueled Adler’s staying power, Hamilton said, “No matter the generation, there’s always a group of people that want to be outside of the box. And that’s what Jonathan’s brand is: Right outside of the box. It’s unique, and everyone wants to feel unique in their own right. His brand provides a visual representation of that.”

Features editor Matthew Wexler chatted with Adler about his decades-spanning career, early champions of his work, and how feeling like an “insular outsider” pushed him to succeed.

Congratulations on the 30th anniversary of your brand. Looking back, did you have a strategy for success, or was it a leap of faith?

It’s funny considering the question in this day and age where everybody has a brand, and where everybody’s an entrepreneur, has a business plan, and identifies white spaces and markets, because that’s really all a new concept. No one in my generation was thinking about it, talking about it, or considering it. So, no, I did not have a business plan. I did not have any thought that I was starting a business at all. I was just making some pots and was lucky enough to get an order. A few years into my journey, I was at a cocktail party with my mother and one of her friends said, “What do you do?” And I said, “Well, I’m unemployed.” And my mother said, “No, you’re not, darling, you’re a potter.”

It’s interesting that it took you some time to own it internally, but you were, in fact, a maker.

I was eking by and thought, this is a cool chapter, but I really have to get a job and make some shekels.

JA: It was Barneys. For young people who don’t know, in addition to being an emporium of the most luxurious and stylish things ever, Barneys was also known for truffling up new creative talent. I knew somebody who knew a buyer, and they came over to my fifth-floor walk-up. They trudged up the stairs and into my little apartment, and I showed them some of my pots. They were like, “These are fantastic.” And they placed an order.

MW: Was there someone specifically who championed your work?

JA: It was Phyllis Pressman, who was sort of the grande dame of Barneys. She was then-chairman Fred Pressman’s wife and ran Chelsea Passage [an area of the ninth floor that connected the original store to an expansion and featured curated local designers]. She loved my work.

It’s amazing because I feel like consumers often just consider the public persona — we see that you’re in the business of pretty things, right? But the amount of time it takes to build something significant and trust your artistic instinct — that’s a whole other story.

The struggle was real!

What made you feel like an outsider? Did you feel that way as a child or in response to being gay?

I would never purport to be a victim in any way, shape, or form. I was an insider in the sense that I grew up in a solidly upper-middle-class family and was lucky to have gone to an Ivy League college. So in that way, I have nothing to complain about. However, when it came to being a potter and trying to enter the world of commerce, I was a complete outsider. I knew nobody in that business. So I really had no idea what I was doing. I came at it from a purely creative standpoint. I was so ignorant about the realities of commerce — how to do an invoice to shipping to business plans and margins — I knew nothing. And I figured it out in an outsider way. I’ve clawed my way into a life of luxury quite accidentally, and I am extremely lucky and delighted. It’s not in any way, shape, or form what I even could have imagined.

Your first exposure to ceramics was at camp, and you’re still often on the wheel. What is it about the tactile process of throwing?

There’s something about pottery that’s primeval, that I think people feel a visceral connection to. It’s very elemental: earth, water, air, and fire. It’s a way to latch on to the desire to be creative and expressive. There’s something athletic adjacent to potting; it’s a very physical thing, and pottery aligns with that side of me.

Over the years, you’ve launched dozens of collaborations with brands like Toms, H&M, Fisher-Price, and most recently, a collection of rugs for Ruggable, which utilizes an innovative two-part system with a rug pad similar to a yoga mat and a washable, stain-resistant, polyurethane coated topper. How do collaborations fuel your innovation and creativity?

Sometimes you need a little kick in the pants. Collaborations are a great way to give a jolt of creativity. Often, it’s one plus one equals three and an opportunity to rethink things and come up with new and different solutions. As somebody who never thought my career would amount to anything, I resolved early on to just kind of say yes to everything.

One of your more notable projects was designing Barbie’s Malibu Dreamhouse in 2009 for her 50th anniversary. Audiences swarmed to director Greta Gerwig’s Barbie film, but I understand dolls weren’t your thing. Did you gravitate toward more traditionally binary boy toys because of the era in which you grew up?

My dad was a lawyer, but he was a passionate artist his entire life, and my mother is very creative. So I grew up in a super artistic, creative home. But growing up, I was very sporty. My relationship with dolls was really about ripping the head off of my sister’s Barbie. So yeah, I think my Barbie association is really sort of an atonement.

I’m lucky to be an applied artist and designer. And one of the things about applied art is that it’s often solution-oriented. It’s like, what could or should this be? When it came time to do the Barbie Dreamhouse, it was just so fun to think about something that I’d never really thought about. It’s not really in my personal or brand DNA, but I was like, “Well, what would Barbie’s Dreamhouse be?”

Related:

Conservative backlash couldn’t stop “Barbie” from raking in nearly $1 billion at the box office

The LGBTQ+-inclusive film is on track to become the first Hollywood movie directed by a woman to make $1 billion.

I visited your new SoHo retail location, which includes a pottery workshop, a design studio, and many of your newest and most notable pieces. What caught my eye was the collection’s vastness — from soft furnishings and sculpture to dinnerware, lighting, and beyond. Are there any big lessons you’ve learned throughout your career about manufacturing and sustainability?

It’s so much more complicated and torturous than anyone would ever imagine. A product is successful when it looks like it was just supposed to be that way — as if it was uncovered rather than created. I want stuff in my store to look like it was always there. Of course, it has an inevitability about its journey, but I don’t really want people to understand the amount of effort that goes into creating something.

In terms of sustainability, I really try not to be hypocritical. So many people these days are comfortable saying they’re a climate activist because, you know, one of the pieces they made has one bit of organic cotton in it. As far as sustainability goes, I make things for a living, which I’m thrilled about. I feel proud of the fact that I make groovy stuff that creates thousands of jobs, but I still make stuff. My one focus is I try to make things that people will not throw away, items of extraordinary quality that will be passed on from generation to generation, and that, I hope, at some point will engender lawsuits between siblings. My motto has always been, “If your heirs won’t fight over it, we won’t make it.”

There seems to be more conversation and consideration of fast fashion, but the ethos that you describe is applicable to home furnishings as well.

Probably more so because home furnishings are big and bulky and take up a lot of space on our planet. So it’s nice if they’re of impeccable quality and craftsmanship.

Are there other queer innovators who you find inspiring, or advice you’d give to up-and-coming designers?

There are so many brilliant young designers, like Gabriel Hendifar and Jeremy Anderson, who co-founded the interdisciplinary studio Apparatus, or the English artist and designer Luke Edward Hall. But the truth is that it’s hard to break through and make a living. My advice: Base your concept of success on your own ideas of creativity. And get a job to pay the bills.

You’re always working on new collections — is there anything recent that speaks to your constant search for new materials and design inspiration?

I have the mind of a hoarder, and there’s so much jiggling around in it, and out of that, I try to create couture, gorgeous products. The Mustique line is really cool. I travel a lot for business and was in India and found somebody who was working in this marbleized acrylic material. Often, a manufacturing process can trigger creativity. They were doing it in organic shapes, but I thought there was something about this material that wants to be in an Art Deco-Memphis idiom. Some things are process- or material-driven, and others just come out of thin air. It happens in a billion different ways.

You describe your aesthetic as “modern American glamour.” Can you define that in more detail?

I pare back gestures to make pieces as clean and clear as they can be. So to me, “modern” is about being innovative and minimalistic, even though people wouldn’t think of me as minimalist. I hope that if you look at the individual products, you’ll see that they are kind of minimalist. “American” is very much a part of who I am and what I do. I’m a raging patriot. I love America and living the American dream. To me, the country is about a spirit of optimism and a place of tremendous opportunity. “Glamour” is a fabulous word that is very hard to define. The idea of glamour is about being memorable. It’s about swagger.

Can we revisit “American?” We’re living in a time when the queer community doesn’t always feel optimistic as we face passed and pending legislation against trans kids, drag performers, and books. Despite all of that, how do you remain optimistic?

Well, I’m not on the first flush of youth. I’m 56. And I grew up in a time when nobody was out. I couldn’t be out; that would have been preposterous. I’m not that old, but the journey that I’ve witnessed for the gay community is extraordinary. I would never suggest that there aren’t a million battles that need to be fought every day. But if you look at a bit of LGBTQ+ history, it’s like night and day. It’s important to appreciate some of the developments and remember the context. If you told me when I was 10 and struggling compared to how my life has turned out – Holy Mother of God.

When did you come out?

At the end of college. But even then, people were just not out.

Because?

I mean, it was just a huge struggle. Of course, I knew from Day One that I was [gay]. But it was a really terrifying time. AIDS … talk about an existential threat. Nobody was openly gay, and if you were, you were going to be smitten. It was hard. I’m no Frank Kameny [a pre-Stonewall activist and the first out Congressional candidate] — I’m not a gay pioneer, but there was a bit of power in being out, even as recently as 25 or 30 years ago. Some of the first publicity I ever got was in a gay publication, which was really cool. It’s so hard to fathom at this point.

But you did find love. You’ve been married to former Barneys window dresser and author Simon Doonan since 2008 —

— I’m glad you told me when we got married because I can never remember!

I won’t tell him, but it’s on your website’s timeline if you ever need to reference it.

Thank you! Yeah, we got married at City Hall in San Francisco in an extraordinarily unromantic way. We were both looking at our schedules one morning and realized we had to travel to California, so we decided to go at the same time. I don’t remember which one of us said, “While we’re out there, we should probably get married.” But we did.

Why was it important to you?

For me, when we moved in together, it felt like the equivalent of being married. We had been together for like 15 years, so it did feel like a formality, but I saw it as a practical thing — I wanted to have all the civil rights that went with marriage.

How did you first meet?

We met on a blind date. We knew who each other was because of Barneys, and I had the hugest crush on him. My friend said, “I have a guy I want you to meet.” I asked who, and he said Simon Doonan, and I was like, “What!” I thought his work was the coolest thing I’d ever seen in my life. And that was before he became a writer. Those Barneys windows were amazing. And he was so cute. Then I met the little monster, and we’ve been together ever since.

You have homes in Palm Beach and Shelter Island. Do you ever disagree on the design aesthetic?

He pretty much lets me do the home. There’s a famous scene in The Boys in the Band where the character of Michael is walking through his apartment and sees two obelisks on the mantelpiece placed on either end, and he rearranges them together on one side to balance the composition. His friend Emory walks past, sees them, and puts them back. Simon and I always joke about gays battling over obelisk placement. We’re not like that. I get on with the interiors; he’s writing and super creative. There’s no fighting and no biting.

We should all have such a copacetic relationship.

Yeah, that’s when you know you’re in a good marriage: When you’re not battling over obelisk placement.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.