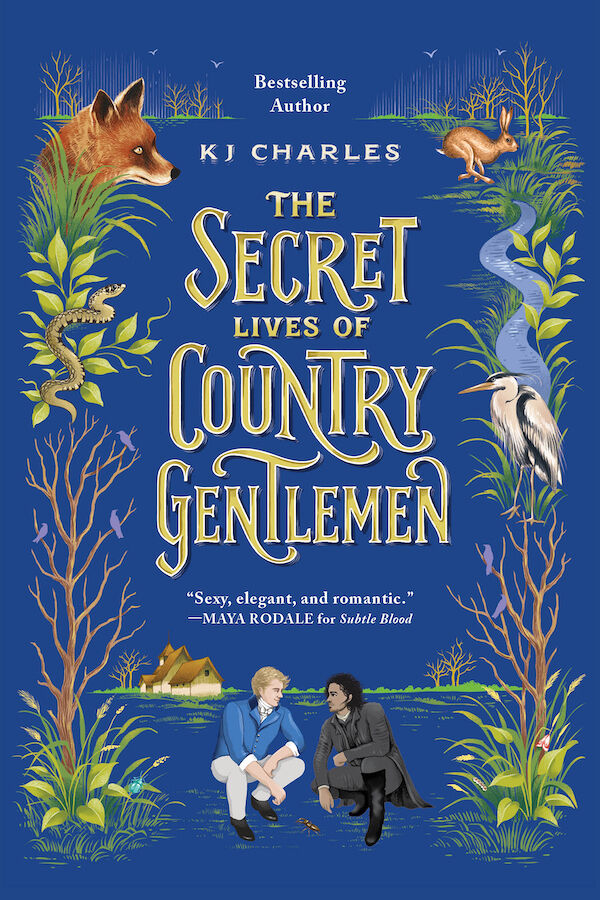

The waistcoats fly off not far into KJ Charles’ gay Regency romance novel, The Secret Lives of Country Gentlemen. It happens in an appropriately country inn, where Gareth, a soon-to-be squire, and Joss, the head of a family of marsh-dwelling smugglers, hook up like there’s no yesterday, today or tomorrow.

Separation anxiety ensues, then a chance meeting, and the romance of two lifetimes, with all the comforting tropes every great example of the genre has to offer, except it’s boys and not bodices being tossed around upstairs from the 18th-century pub in South East England.

Related:

“Red, White & Royal Blue” proves sex scenes can indeed be revolutionary

Finally, a film shows what sex is actually like between two men in love.

Author Charles cut her teeth on romance as an editor at London publishing houses specializing in the genre, then struck out on her own as a writer. Now she has dozens of historical titles to her name, most of them series, an indication of her savvy in hooking readers on her colorful, yet identifiable characters. A sequel to Secret Lives is due in September.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Gay romance has taken off in the last few years, with the popularity of books like The New York Times best-selling novel Red, White and Royal Blue by Casey McQuiston — now a hit movie — and the recent Boyfriend Material series from Alexis Hall.

While both of those hits are contemporary, Charles mines the past for her stories, opening eyes and history to the torrid romance that was always there between the lines.

I spoke with the author about her new book from a country house in the South of France, where she was vacationing with family: a supportive husband and “two eye-rolling teenagers.” She left the “cat with a history of violence” at home in London.

LGBTQ Nation: When I was researching new books for 2023, I was fascinated to find out there’s an extensive subgenre of gay-themed romance novels. When did they get so popular?

KJ Charles: In the last seven, eight years there’s been a boom in publishers who have taken on gay romance. When I was working in publishing, they wouldn’t have done anything except, you know, your basic male-female romance. I don’t recall a bisexual character ever. I don’t recall anyone ever proposing that a character should even be bisexual and in an MF [male/female] romance. The change in that has been really dramatic over my working life and really notable.

When I got my first book published, it was with a small publisher, and it’s small independents who are really leading and establishing gay romance and lesbian romance and bi romance and actually doing the rainbow. A lot of small publishers really put a lot of work into it. And in the last, almost four years or so, you’ve really seen that boom into the traditional publishers, and books actually getting on the shelves.

LGBTQ Nation: Because they’re selling.

KJC: Publishers don’t do things because it’s the right thing to do. They do it because they make money. Sorry, but if you’ve ever met a publisher, you’ll know that this is the case. But they do, they make a lot of money. I mean, you’ve doubtless heard of Red, White and Royal Blue, maybe Boyfriend Material. These are books that have sold just a truckload. Basically, publishers like it when you sell a truckload of things.

LGBTQ Nation: Like romance novels in general, a lot of gay romance is written by women. What’s the draw for this kind of writing, particularly male romance, by women like you?

KJC: I think it’s rather hard to pin that one down, because some people just like to write a variety of people. Some people find it much more productive and satisfying specifically to write outside their own experience or their own existence.

Also because historical romance — historically, as it were — has been really, really white cis het, and it was a big issue before Romance Writers of America imploded, which they did a couple of years ago. There was some really sort of terrible bigotry that was coming up in terms of racial issues and issues of gender and sexuality. So I think a lot of people are actually quite conscious that they actively don’t want to be contributing to some of the things that make historical romance actually quite, in many ways, quite an unfriendly closed shop. That’s still being pushed against now, which I think is a satisfying thing.

LGBTQ Nation: I’ve read posts by other romance novelists referring to the sex in their books as “smut”. Is that some kind of inside, sorority reference?

KJC: I don’t call it that. I think that’s quite a belittling word, to be honest.

LGBTQ Nation: I think it was used tongue-in-cheek.

KJC: There’s a lot of tongue-in-cheekiness in romance, but there’s also quite a lot of defensiveness because it’s a genre which is primarily associated with women. It’s obviously the target of an awful lot of misogyny. And one of the ways misogyny expresses itself is that there is a lot of belittling language and a lot of mockery and a lot of finding it funny and hilarious that people write a lot about sex. So I think it’s one of those areas where, you know, people are more inclined to making jokes than to enjoy it when other people make those jokes at them, if you get what I mean.

LGBTQ Nation: Some of our readers might be curious how a cis straight woman writes so masterfully about gay men having sex.

KJC: Well, I’ve written an awful lot of murders, as well.

LGBTQ Nation: (laughing)

KJC: I’m an editor, as well, and I’ve written quite a lot of advice on writing sex scenes, because it’s actually technically quite demanding to write a decent sex scene.

LGBTQ Nation: Who are your readers?

KJC: Sort of depends on the book. I’d like to say my readers are just people who enjoy romance novels, because I feel very strongly that if you enjoy romance novels, you should enjoy all kinds of romance novels about all kinds of people. Reading is our window on the world. And it’s our window into other people, and I’m a big fan of there being an extremely wide range of them done as mainstream.

LGBTQ Nation: If I read all of your books, what would be the most common elements that I’d find?

KJC: On the one hand, murder, because I’m notorious for my high murder rate. Somebody actually did an infographic working out what my body counts were, and it’s horrible.

Also, that my characters have friends, they have a support system. They develop people that they’re safe with and they can trust. With historicals — when they’re set in Britain, especially, with the vile history of this country — you want to know not just that your characters have a happy-ever-after, but they’ve also got a group of people who are supporting them and keeping them safe. I think it may give that additional sense of security, which is really what you want at the end of a romance novel, that they’re sure everything’s going to be alright.

LGBTQ Nation: Secret Lives looks at the romance of two men from different classes. What makes that a particularly British arrangement?

KJC: Well, (laughing) Brits and class. We’re all obsessed with it. But actually, I love writing cross-class romances, partly because I am not a huge fan of extremely aristocracy-skewed examples of the genre. But mostly because with cross-class you’ve automatically got problems, and the art of the romance novel is to set up a situation where, very often at least, there’s a massive problem, and you’ve got enough problems to keep two people who are perfect for one another apart. Otherwise, you haven’t got a book.

So, the fact that Joss is a smuggler and Gareth is a baronet — albeit not a very good or experienced or important baronet — it’s enough to be a little bit of awkwardness. They don’t automatically understand one another. They’ve got a lot of work to do before they understand one another. Which is relationships for you, isn’t it?