Most readers know that my day job is as a screenwriter, and I’ve recently finished a screenplay that tells the story of The Sound of Music from the point of view of the “bitchy” Baroness Schraeder.

Here’s the synopsis:

BARONESS (Horror-Comedy): When a baroness is invited to the estate of her widowed boyfriend to meet his seven children, she becomes convinced that his plucky new governess is hiding a dark secret, and that the hills surrounding his lavish estate are alive with more than just the sound of music.

I had a ball writing this script, in part because I think the scheming, sardonic Baroness is easily the most interesting character in The Sound of Music, and Eleanor Parker’s admittedly over-the-top performance is also the film’s best — definitely better than Peggy Wood’s one-note Mother Superior, who, inexplicably, was the only actor other than Julie Andrews nominated for an Oscar.

Incidentally, how does one get the rights to dramatize such a well-known property as The Sound of Music? Well, if you’re writing a spec script like I am, you don’t. You thinly disguise the characters and stress that the project is a “parody,” which falls under a different set of legal rules, all the while hoping to also maybe interest the current rights-holders.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Not surprisingly, the process of writing this script has me thinking about villains in general.

There’s a saying among actors that the villain is often the best role in a given script. Hannibal Lector? Darth Vader? Nurse Ratched? Freddy Kruger? Jigsaw? Bellatrix Lestrange? Norman Bates? These are certainly some of filmdom’s most memorable characters.

Why do actors and audiences find these characters so interesting? I think it’s, in part, because they’re complicated. There’s another saying, one among writers, that very few people think of themselves as “evil” — that we’re all the hero of our own story.

It’s certainly true that a villain with an unexpected, relatable reason for the way they act is far more interesting than someone who’s just innately bad.

Case in point, before she died earlier this year, Louise Fletcher gave her fascinating take on Nurse Ratched, the character she made famous. Nutshell? One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is about a woman whose male patients refuse to accept a woman in a position of authority.

And Fletcher has a great point: the take-down of Nurse Ratched by Randle McMurphy — in the hospital, in part, due to a charge of statutory rape — plays differently in the post-#MeToo era than it did in the 1970s.

Needless to say, villains are currently having a moment in the sun.

First came the anti-hero, in the “auteur” film era of the 1970s, and then later in the 90s and 00s, with the rise of prestige TV. These movies and TV shows weren’t aiming for mass appeal, so they could dare to feature main characters who struggled to do the right thing — and often acted in selfish, self-destructive ways.

We also saw leading characters who are outright evil, in movies like A Clockwork Orange, TV shows like Breaking Bad, and Broadway musicals like Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

These days, even movies with animals terrorizing humans now give their antagonists a sympathetic backstory. In last year’s Beast, Idris Elba is terrorized by a rogue lion on the African safari — but not before showing us how the lion’s entire pride is killed by poachers, giving him an understandable hatred of humans.

And it seems pretty clear that in Cocaine Bear — the upcoming movie that recently got the internet so excited — the bear in question is going to be as much victim as villain.

Compare these movies to 1975’s Jaws, where the giant shark somehow develops a scientifically inaccurate taste for human flesh and just…eats people.

For the last several decades, we’re now seeing the curious phenomenon of writers taking the villain from a famous existing story, and then retelling the story from the villain’s point of view.

Wicked, which tells the story of The Wizard of Oz from the point of view of the Wicked Witch of the West, was certainly not the first example of a writer doing this. But when the 1995 novel by Gregory Maguire became the insanely successful 2003 Broadway musical, a new genre was created, and soon we had more entries, like Maleficent, Despicable Me, Cruella, and God knows how many different versions of How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

On TV, we’ve now had entire series devoted to retelling the stories of what I just said were some of the most memorable villains of all time: Hannibal Lector in Hannibal, Norman Bates in Bates Motel, and Nurse Ratched in Ratched (which was a typically hamfisted and ridiculous Ryan Murphy production, not nearly as interesting as Louise Fletcher’s take on Nurse Ratched that I outlined above).

Sadly, we also have fifty zillion superhero villain projects currently in the works, and I’m 100% certain we will soon see a retelling of virtually every animated Disney movie from the point of view of the villain. Why not? Given we’ve already had live-action remakes of most of these movies, and Broadway musicals, and television “celebrations,” we already know Disney has no shame whatsoever.

Incidentally, I want it noted that I had the idea for Baroness ten years ago, after Wicked but before our current glut of villain retellings. But hey, what writer doesn’t like to see the genre he’s chosen explode in popularity?

Why is that all happening now?

I think it’s partly because we live in a depressed, cynical era, and “dark” now sells. It’s easier to find traction for characters who argue, “Burn it all down!” when more and more people want to, well, burn it all down.

But I think these villain retellings also speak to society’s sophistication — the growing awareness that previous moral codes were selective and hypocritical, and that morality in general is a difficult business, often complicated and elusive. TV and movies are no longer made in black-and-white, in more ways than one.

These stories also speak to our media sophistication — or maybe our media jadedness. Over the last four decades, the Western world has become absolutely inundated with “content.” Back in the 1970s, Hollywood gave us a few dozen scripted TV shows every year; now there are over 500. The number of feature films is up almost as dramatically.

As much as I love the Hero’s Journey, I can only hear it so many times. At some point, viewers and writers both can’t help but think, “Huh, I wonder if there’s any other way to tell this story.”

You also start to think, “Yeah, yeah, I’m really glad Carrie Bradshaw and her friends are enjoying New York so much, but what else ya got?”

The way I see it, there are two ways you can write a story from the point of view of the villain.

The first way is to keep the essential outline of the original story but show us the villain’s backstory — often, their origin story. Here we learn the things we never knew about the villain, and also the reasons why they ended up so bad.

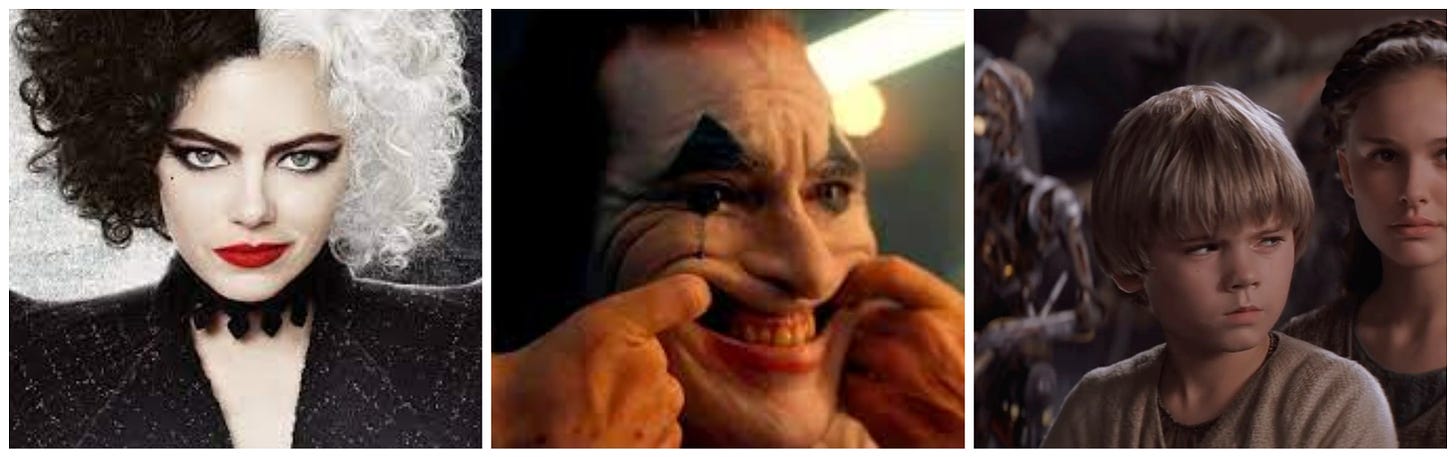

In this kind of retelling, as with Cruella, Joker, or Ratched, the villain is still “the bad guy,” but now we understand them better. Sometimes we may not care about their reasons for being bad, as in Ratched, or George Lucas’ three flawed Star Wars prequels that tried to explain Darth Vader. But hey, at least we have them.

The second way to reclaim a villain is to retell the original story but to also show how the version of events we think we know was limited or even outright false. And with this additional information, we come to see that the villain isn’t really a villain at all — is more of a victim, and might even be the real hero of the tale.

This is the technique taken by Maleficent, Wicked, Bates Motel, and, well, me.

In Baroness, Maria — or “Marina” in my screenplay — seems to be the same plucky governess from The Sound of Music, going on outings and teaching songs to the seven “van Trope” children. But, in fact, she has much more nefarious designs, the result of her spending so much time in the hills around Salzburg, eventually consorting with evil forest gods. Alas, only the Baroness can see the horrifying truth of what’s really going on.

This is, in part, a feminist retelling of The Sound of Music. No, the Baroness is not insane, despite what the men say, thank you very much. But the script also deals with class. The Baroness is rich, after all. And Marina is from the lower class.

But as a writer, I live to subvert expectations, which is why one of my favorite lines in the whole script is when the Baroness confronts Marina, saying: “I’m really sorry you had a bad childhood, but it’s still not okay to sacrifice seven children in order for you to become a forest god!”

There’s technically a third way to tell a villain’s story, which is to present the villain as just as evil as always, but to also portray them as totally cool and edgy — essentially, someone to be admired.

I think this can work, as in movies like Black Panther, which I didn’t like as much as the rest of the world, but even I can see how the whole point of the film is to show that the morality of social movements can sometimes be complicated with no easy choices.

But offering up “cool” villains can also be unduly cynical and even outright nihilistic, as in most of the movies by Quentin Tarantino, which often leave me feeling like I need to take a shower. I’m also certain that oh-so-cool villains will be the take on all these upcoming superhero villain stories, since I’m now convinced the whole point of every single superhero project ever is just to personally piss me off.

Call me old-fashioned, but there are already so many voices in American society telling people to be more selfish and more narcissistic. Do we really need voices telling people to be more sociopathic too?

But, of course, I should reserve judgment, at least until these movies are released. After all, if I’ve learned anything from my own villain retelling, it’s that people and things are often very different from what they first appear.

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author, and one half of Brent and Michael Are Going Places, a couple of traveling gay digital nomads. Subscribe to their free travel newsletter here.