“I need to have a conversation with you,” said Lee County sheriff Daniel Simon to Brian Alston-Carter, a candidate for the South Carolina House of Representatives, at a 2014 campaign event. “I need you to ride with me to see something.”

Simon provided Alston-Carter with a police escort as the pair drove about five miles on Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Highway to one of Alston-Carter’s campaign posters. A shotgun had blown a picture of his face off the sign.

“I’m not a fearful person, so it didn’t scare me,” he said. “If anything, it motivated me more.”

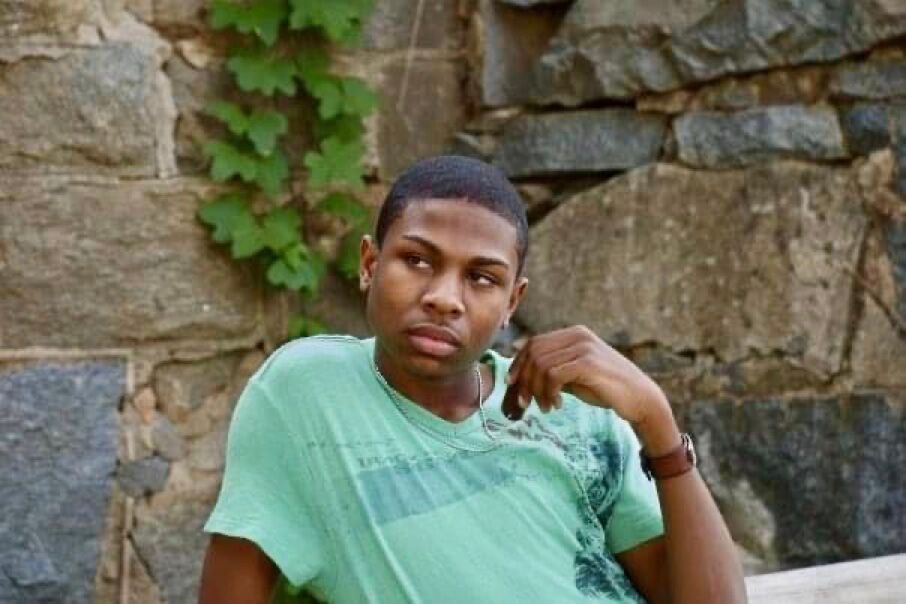

Motivation is a quality Alston-Carter does not lack. To many, Alston-Carter — who identifies as a “same-gender-loving” Black man (or SGL, a culturally affirming term coined by activist Cleo Manago) in a conservative county — was a longshot in his attempt to unseat incumbent Rep. Grady A. Brown, a local businessman who had held the office for 30 years, in the Democratic primary.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

And, in fact, Alston-Carter lost. Later that year he lost a race for a school board seat. He ran for the statehouse again in 2016 and lost. Then, in 2018, he ran again for Sumter School District Board of Trustees, Area 1 — and won.

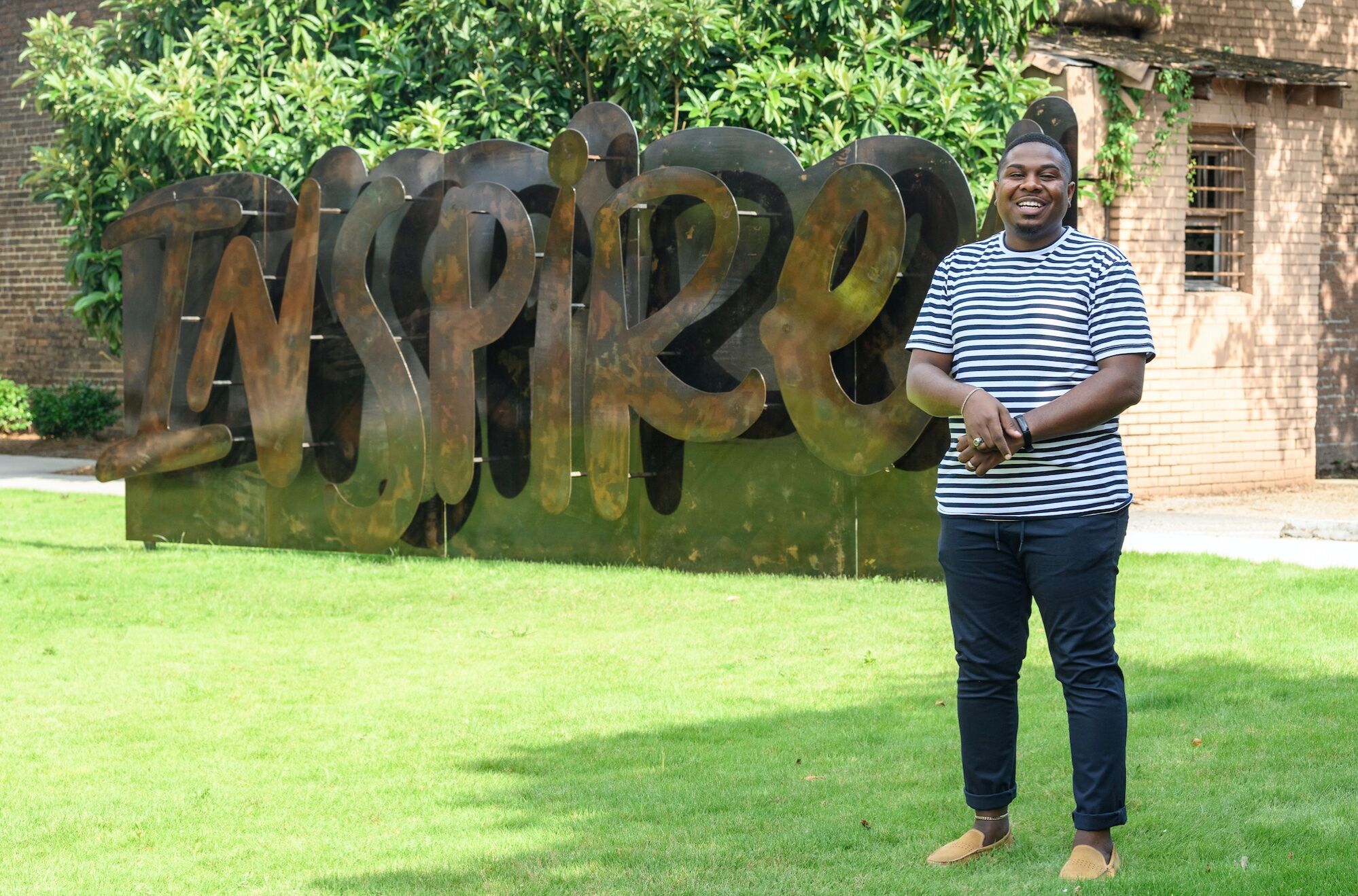

“I think that my mere presence on the board has moved the dial because representation truly matters and makes a world of difference. It has allowed the seemingly invisible and voiceless to be represented with a seat at the table.” — Brian Alston-Carter

A glance at the county’s demographics shows just how impressive Alston-Carter’s determination really is. While support for equal rights has trended upward since 2015, with 70 percent of Americans now in support of same-sex marriage, there has been little progress in Alston-Carter’s tiny hometown of Rembert or across the state of South Carolina when it comes to equality.

In January the Republicans proposed House Bill 4605, which would prohibit the teaching or discussion of “discriminatory concepts” in public, charter, and private schools from kindergarten through college or any other entity that receives public funding, including nonprofit organizations and private businesses. The bill would restrict how gender, sexual orientation, and race are taught.

This is the political climate that Alston-Carter and other LGBTQ leaders navigate in small rural areas, especially in red states, across the politically divided nation.

Alston-Carter stands on the shoulders of a resilient family, who for generations forged a path in the historic town of Rembert, population 219. The oldest of four siblings, Alston-Carter, 33, was raised in an intergenerational household with his mother, uncle, and grandparents. His grandmother, whom he affectionately called “Nana,” worked as an administrator for 42 years before her death in 2015 in the school district that Alston-Carter now serves. It’s also the same school district in which Alston-Carter received his primary and middle school education. He distinctly remembers there being only one traffic light in the entire town, which is about 40 miles east of Columbia.

Alston-Carter says the support he received from his family planted the seed for his political ambitions.

“I’ve known education and hard work my whole life,” said Alston-Carter, who in addition to his public service works full time for the South Carolina Department of Administration’s Office of Economic Opportunity. “My family has always poured into me and made sure that I had the best opportunities and the best exposure when it came to education and life experiences.”

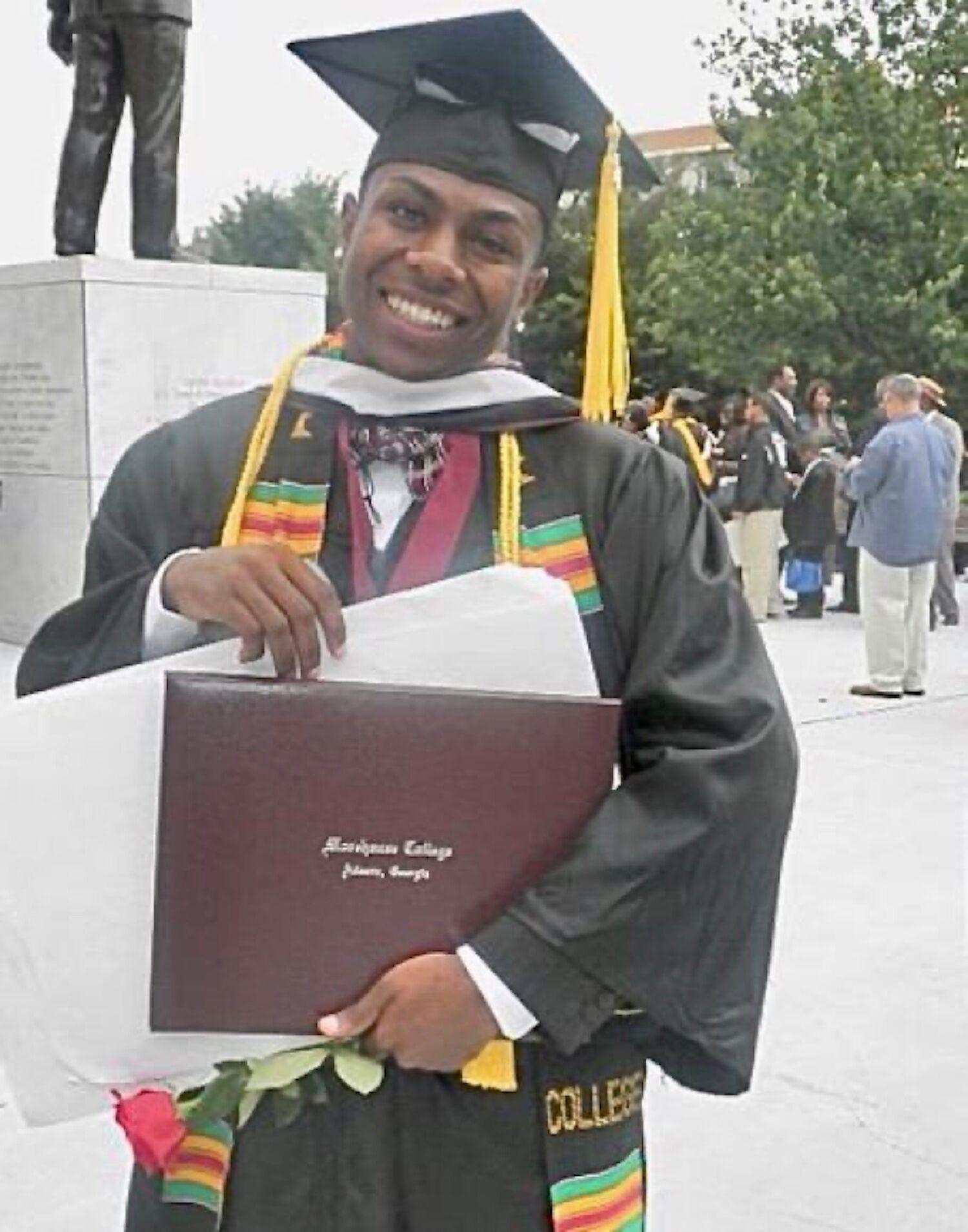

Alston-Carter’s decision to attend Morehouse College, a historically Black liberal arts college in Atlanta, would prove liberating. The freedom that defines Black queer life in Atlanta inspired the small-town guy and landed him inside “The Mean Girls of Morehouse,” a 2010 Vibe Magazine article profiling queer and gender nonconforming Morehouse students who openly rejected the school’s conservative dress code policy.

With an increasing number of anti-LGBTQ laws going into effect across the country, protecting the rights of queer Americans has become even more imperative. Young people in rural communities are at even greater risk. Research indicates that nearly half of queer youth in rural areas and small towns feel their communities are “somewhat or very unaccepting of LGBTQ people.”

LGBTQ Nation talked with Alston-Carter about the pivotal moments that led to his coming out, his multiple runs for office, the challenges of Southern politics, and why he’s committed to making a difference in local politics.

What kind of messages do you recall receiving in Rembert, where you grew up?

Being from rural South Carolina, I’d heard everything from “Oh, you know, he’s a little sweet” and “He’s got sugar in his tank” to “He’s funny-acting.” That’s something that always sticks out in my head. Girls felt like I was too preppy or well-spoken, so I guess they made me know that something was different about me, but I didn’t know [what the difference was] at the time.

Is there community in Rembert today? Are queer students and their allies able to form gay-straight alliances in Sumter schools?

There’s no gay-straight alliance in our schools. It’s something that’s kind of unspoken. Basically don’t ask, don’t tell. Of course, we know each other in the community, but it’s just something that’s really not discussed openly. When you get into the city of Sumter, as opposed to being in the town of Rembert, the city is a little more open. There’s more visibility in the city.

You serve as the chair of the Policy Committee, a forum for discussion designed to provide recommendations for modifications to board policy. How are you utilizing your power and visibility as an openly SGL member to influence policy?

Our school board association sent down a very vague equity and education policy that we adopted expressing our commitment to providing equitable educational opportunities to all students regardless of gender, race, and ethnicity, with no explicit mention of sexual orientation or gender identity. I thought we needed to go a step further. In South Carolina, there are only two or three school districts that have equity policies. It’s something that I saw as an opportunity to put us at the forefront to make our district a little more attractive to say that we have an equity policy on the books. We will use the results of an equity audit to craft a district-specific equity plan.

How will this plan impact students?

It will look at the services and support being offered to students and staff. It will look at whether we’re embracing the community when it comes to our hiring of teachers and staff across the district. Are we addressing bullying issues? This year alone, there were two trans students that graduated. Their names were called based on how they identified. And so it’s those moments that give me pride to be on the board. They may have never seen someone that can relate to their story sitting where I sit.

Growing up, were there adults in your life that affirmed your humanity?

No. I don’t think I had any LGBT teachers. I don’t think I had friends with parents that came from same-sex households. I think I would have been more comfortable with myself earlier in life. I think a lot of it was feeling out of place or a sense of not belonging, or, if you will, weird.

Who is a role model?

My ultimate role model is Huey Newton [co-founder of the Black Panther Party], who happens to be my [Phi Beta Sigma] fraternity brother as well. His quote: “Maybe a homosexual could be the most revolutionary.” I embrace that and I use that during the moments when I’m arguing for or against something in my capacity on the board. I think it does open a door for more same-gender-loving individuals to serve in this capacity.

How did you ultimately decide to come out?

I was actually outed to my mother by the guy that I was dating at the time over the phone. We were in the car. I remember him saying, “I’m tired of hiding.” My baby brother was in his car seat.

How did your mother react?

She pulled to the side of the road. She said she felt like she failed as a parent. “What did I do to deserve this? All that I’ve done to try to protect you, and this is the thanks that I get?” So we went through all of that. Finally, we get back on the road to go home. We pull up at home, and she says, “Don’t come into my house.” I attempted to get back in my car, and she said, “No, you need to give me your keys. You need to give me your laptop and give me your cell phone. I’m not taking care of you if this is the life you want to live. You need to go do that somewhere else.”

And I said, “OK, I’ll go back to Nana’s house.”

She said, “Well, you’re gonna have to tell her to come and get you. You’re not driving the car. And I’m not paying for you to go to school.”

I stayed in the car the majority of the night, and eventually, my stepdad came home and was like, “No, you can come in the house.” My dad and my stepdad have been very supportive. My mom was the only one that had an issue.

Why do you think your grandmother was so supportive?

She grew up in Rembert, but she would spend the summers with her aunt in New York. And so those experiences of being in a big metropolitan city and being exposed to a life that looked completely different than what she was accustomed to here. With her being in education, she was exposed to people from all walks of life. And I think that made her more open-minded than those that just didn’t have those life experiences.

Did you remain in contact with your high school boyfriend after you were outed?

We stayed in contact during our transition to college. He died by suicide. I spoke to him the night before. Our conversation was nothing out of the ordinary. The only thing I remember him saying was that he was still struggling with his sexuality, playing sports, and transitioning to college. Outside of that, it seemed normal. The next morning, his ex-girlfriend called me and she said, “I need to tell you something. They found Pat dead this morning in his dorm.” I think that was the thing that made me comfortable to say, “OK, if he struggled with this, then I can’t continue to live this lie.”

Are you in a position to have conversations with your colleagues about policies that would ensure the safety of LGBTQ kids in school? Are they open to such conversations?

If that conversation would come up, it would be pushed aside just because of the makeup of our board. Me and my colleague, Dr. [Shawn T.] Ragin are the two youngest members of the board. There are two that are in their 50s and then everybody else is 65-plus. So that’s not a conversation that they’re willing to have. We are constantly graduating students who are more and more diverse. And so this old mindset of homophobia — I think they’re gonna be outnumbered because the younger generations are more and more progressive and they’re going to drown out that noise. There’s this belief that young people should wait their turn and not use their voice until asked to do so. But that causes change to be stagnant and hinders progress. At every turning point in history, young people have been at the forefront. We’re seeing this nationally once again, as history is repeating itself.

Did House Bill 4605, which could prohibit the discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity in the classroom, come up in board meetings?

The context and content of H. 4605 has come up in board meetings by a member of the community but not the governing body itself. Thankfully, the bill died this legislative session and would have to be reintroduced next year for further discussion. Fingers crossed that it does not!

Is there anything you feel you can do on a local level to counter this kind of state-driven legislation?

At the local level, we can use our voices and the authority granted as the governing body of the school district to implement policies such as the proposed district-specific equity policy that’s forthcoming to counter this state-driven legislation. We are responsible for equipping our students to be “global” citizens. Our policies should and must speak to creating global communities that embrace diversity, inclusion, and equity for all.

Have you been able to move the dial with fellow board members on issues like this and find common ground?

I think that my mere presence on the board has moved the dial because representation truly matters and makes a world of difference. It has allowed the seemingly invisible and voiceless to be represented with a seat at the table. We find common ground when our voices are heard and our experiences are shared. This is a continued work in progress but I’m hopeful because conversations that once wouldn’t be up for discussion can now be had amongst my peers.

After graduating from Morehouse, you briefly moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, before returning to Sumter to care for your grandmother before launching your first campaign for the South Carolina House of Representatives in 2014. What inspired you to run?

A well-respected pastor in the community, the late Rev. Dr. Willie Dennis Sr, of Union Missionary Baptist Church stopped by my Nana’s house, and he told me there was an election coming up, and he thought I should move home and run for it. I hadn’t lived in this community since I was in the eighth grade. He told me, “Pray on it. Think about it. And I’m praying that you will go for it.” And so, I started thinking about it, and I was like, “Nothing has changed in the area in my lifetime. Why not give it a shot?” The person who held the seat at the time would’ve been in the seat for 30 years at that point. So basically, my whole life.

Were you concerned that your sexuality might be weaponized against you in your bid for office?

Before I decided to run, I had a conversation with my family because I had already done the “Mean Girls of Morehouse” article with Vibe. And I said, “You need to be prepared because politics is dirty. My sexuality is a soft target. And I don’t want you all to be caught off-guard by anything that’s said or whatever may transpire on the campaign trail.”

Have there been other instances?

Yes, I’ve received death threats. Just to know that in 2014, you’re a young, Black, same-gender-loving candidate, and you’re facing things you read about in textbooks or that you see in movies from the ’60s. A Black guy walked up to me and said, “You know, people get killed for running against him [Grady Brown].” I said, “Was that meant to scare me? Because I’m going to run my race.”

You were unsuccessful in your first bid for state rep. in 2014 and again in 2016. You also lost your bid for a seat on the school board in 2014. What motivated you to keep going?

I came within 532 votes of unseating [Grady Brown]. It was the first time anyone had won a county in the district against him. I won my home county in that race. But after I lost the 2016 race, I was like, “You know what? I’m not running anymore. Elections are too expensive. I’m just going to stay involved in the community, but I’m not running.” Yeah, that’s what I thought. The community kept pressing me.

Those conversations were really about the [reality that the] leaders of our community are aging. And if we don’t start preparing or giving people like me an opportunity to serve, then who’s gonna be our leaders? There’s gonna come a time when our leaders are either gonna age out where they can’t effectively serve, or they’re going to die in office, and we’re gonna be scrambling looking for leaders. So it was always about providing the opportunity for not only me but other young people in the community to pick up the mantle and run with it.

So then we get to 2018, and I said, “OK, I’m going to run.”

And you did. Your 2018 campaign for the Sumter County School District Board was successful. What was different about this campaign? Did the homophobic attacks continue?

This race was different. I’d learned so much from my previous three runs for office. I was a little more politically savvy. It felt different. The support felt different. There was excitement around the run until a month before the election. The [then] chairwoman of the Democratic Party, Barbara Bowman, a Black woman, was running for the board as well — for the same seat. I received a recording of her using very homophobic slurs to describe me and my family members. She took issue with my eyebrows. She said she’d never seen a man with eyebrows so perfect. I was called the F-word.

It bothered me because she’s a Black woman. She could be my mother. It just brought back those feelings from our issues. It was a month before the election. We’d made it all the way here, and now this comes up. And then she issued some watered-down apology. But my issue wasn’t with her offending me; it was that you’re running to serve on a school board where you have LGBTQ kids, LGBTQ staff, parents, and other stakeholders in the community that you have offended. How can you represent them?

On the first day I was sworn in, I was nominated to be chairman of the board. Well, I heard chatter afterward. “We couldn’t allow that to happen because the county would be in an uproar to have an openly gay man as chair.” We have reorganization meetings every election cycle, and it comes up again because, at this point, I’m engaged [to be married].

“I think what this is doing is igniting a flame for change. We’re seeing more and more young people become involved by taking an active role in the political process.” — Brian Alston-Carter

Congratulations! You and your partner, Shane Wilson, were engaged in 2019. It’s rare to see two Black men partnered and visible in a small conservative town like Rembert. Is he excited about your re-election campaign?

I did not tell him when we first started dating that I was on the school board. He kind of found out along the way. But he’s embraced his role. When we go to visit schools, kids run up to him just as much as they run up to me because they’ve become so familiar with him. And I think that some kids know [we’re a couple] and some may not.

He doesn’t want me to run for re-election. The amount of stress I’ve been under within the last six months with being pushed to the forefront of the media — the news calls almost daily for a comment — board meeting after board meeting. It’s been a lot. But he knows that I’m running. I’ve been endorsed by the Victory Fund, so that solidifies I’m running.

The question about public displays of affection is one of our biggest arguments. He’s not comfortable with public displays of affection here. I have an “I don’t care” mindset. We could be in a store and I’ll say, “Oh, hold my hand.” He’ll be like, “No,” or he’ll hold my hand, and then we’ll walk around the corner [and see] somebody coming and he’ll be like, “Get off of me.” I guess his experience is different from mine. He’s lived in Sumter his whole life. I’ve lived in Atlanta. I’ve been to Charlotte. I’ve been to Columbia and then back here, so my experiences are different. My level of comfortability is different from his.

If your re-election campaign is successful, will the two of you remain in Sumter after completing your term, or will you become the newest transplants of a larger, more queer-friendly city?

He wants to leave. I’ve had the experience of living outside of South Carolina. He has not had that experience. There’s this running joke that we are the first family of Rembert. It’s those moments that I see the change. In a rural community, an openly gay couple can be looked at as the first family. They look to us as being the leaders of the community.

I think what this is doing is igniting a flame for change. We’re seeing more and more young people become involved by taking an active role in the political process. We’re seeing them not only out here registering people to vote, but we’re seeing them running for and serving in various offices. I just think that we have to do a better job of supporting those that want to challenge the status quo. Every time change has come to the country, it’s been at the hands of young people. I think by us being visible in the community it’s gonna make a difference. There is another Brian and Shane in the community that’s searching for someone to look up to.

And so we have to continue to be visible. We have to continue to be vocal and we have to continue to fight.

Editor’s note: This article mentions suicide. If you need to talk to someone now, call the Trans Lifeline at 1-877-565-8860. It’s staffed by trans people, for trans people. The Trevor Project provides a safe, judgment-free place to talk for LGBTQ youth at 1-866-488-7386. You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

Darian Aaron is communications director of CNP (founded as Counter Narrative Project), a nonprofit organization that shifts the narratives about Black gay and queer men to change policy and improve lives, and editor-at-large of The Reckoning, a digital platform focusing on Atlanta’s LGBTQ community.