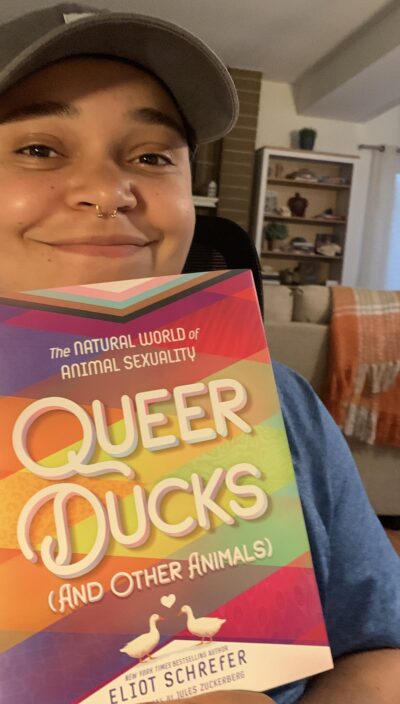

Like a lot of the behavior Eliot Schrefer describes in Queer Ducks (And Other Animals): The Natural World of Animal Sexuality, his book is hard to classify. Is it a science textbook? A queer kid memoir? A college thesis illustrated with Far Side comics?

It’s definitely not a traditional science textbook. “Traditions,” Schrefer writes, “are just peer pressure from dead people. We get to make new ones of our own.”

Related: 5 things you should definitely bring to Pride

So what is it?

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

First of all, don’t judge the book by its cover, which teases you in Skittles rainbow colors that the subject is LGBTQ. It is, but inside it’s as monochrome as a newspaper circa 1979.

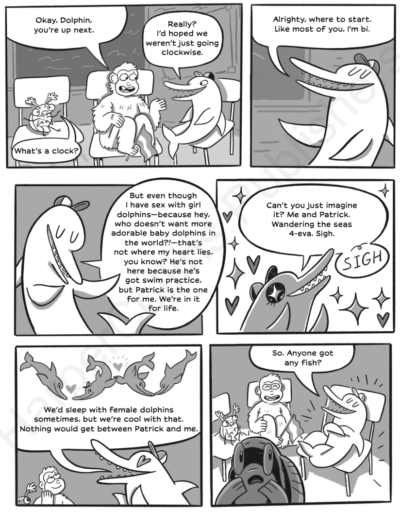

Comics by Jules Zuckerberg recall Gary Larson’s chatting animals and break up chapters on different species. Interviews with young working scientists describe how and why science is gathered, and by whom. And throughout, Schrefer adds personal context to his different subjects.

“I was around age eleven when I started lingering over the Fruit of the Loom ads in my brother’s Rolling Stone and realized I was attracted to other guys.”

This doesn’t sound like the musings of a traditional scientist, and Schrefer isn’t. With a BA in Literature from Harvard, he’s a writer first, primarily of Young Adult fiction, which helps explain his fluency in a book directed at teens. But he’s also queer and a part of the Animal Studies master’s program at New York University, where he learned this academic truth: “Science is made by scientists, and the way they think about the natural world is reflected in their explanations of it.”

In other words, who is doing the science-ing matters, and on the subject of animal sexuality, the science, until recently, has fallen short. Queer Ducks, it turns out, is as much a history of human sexuality, homophobia, and confirmation bias as it is a study of those queer ducks.

Schrefer writes: “The ‘scientific truth’ about animal sexuality hinges on whether the writer continues to hold animals as sacredly heterosexual, in what we might call the Noah’s ark version of life, or whether they allow themselves to be informed by the undeniable evidence of same-sex sexual behavior.”

And there’s a lot of evidence.

“In 1999, researcher Bruce Bagemihl released his exhaustive, meticulously researched Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, and over the years that followed, in species after species, across the vertebrate and even invertebrate worlds, research has shown same-sex pairings in hundreds of animal species. And not just occasional link-ups—sometimes lifelong partnerships between animals of the same sex.”

Schrefer zeros in on several species to illustrate particular behaviors in chapters like “Ducks and Geese: What’s the animal stance on polyamory?” “Bonobos: Do we learn homosexuality or heterosexuality—or just unlearn bisexuality?” “Albatross: Does sexuality require sex?” “Deer: Are there trans animals?” And “Bulls: What could be manlier than sex between a couple of males?” (Apparently, nothing turns a bull on more while they’re getting jacked off than being watched by another bull.)

There’s a theory behind most of these behaviors. “Polyamory—the bonding of three or more animals, instead of the conventional two—can expand the effective pool of parents, increasing the survivability of offspring. There’s also a theory known as ‘bisexual advantage,’ coming from data showing that fluid sexuality increases reproduction chances across a population, making bisexuality ‘an evolutionary optimum.'”

For some sexual behaviors in some animals, like humans, there is no scientific explanation. In the late 19th-century, French entomologist Henri Gadeau de Kerville “distinguished between doodlebugs who are driven to same-sex sex by lack of females, and those who just . . . like it (‘pédérastie par gout’).”

Like some humans just like it. Or not.

“There was a particular bloom in female-female households in New England in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, enough that the term ‘Boston marriage’ came to describe women cohabitating and spending their lives together, whether the union was sexual or not,” Schrefer told LGBTQ Nation.

Like your “old maid” aunts, nearly a third of albatross pairings are female-female. Are they just “making the best of a bad job”?

“There is a strong drive to explain away female pairing in particular in scientific literature,” Schrefer said, “reducing it to ‘females getting by’ rather than considering it a chosen union.”

Schefer points out that lots of societies have considered same-sex couplings a fact of life.

“One significant historical study of all known human societies throughout history found that 64 percent sanctioned or embraced same-sex sexual behavior. Especially substantial numbers of homosexual relationships are found in seventeenth-century feudal Japan, the Mayan civilization, fifteenth-century Florence, and the Indigenous peoples of North and South America.”

And in Greece: “As they grew older, men would generally go from passive eromenos to active erastes. As Diogenes Laërtius wrote about the desirable Alcibiades, an Athenian general, ‘in his adolescence he drew away the husbands from their wives, and as a young man the wives from their husbands.'”

Like dolphins, Greek society relied on social bonds that were cemented through male-male sex.

“Sex,” writes Schrefer, “is a social glue.”

So who is writing the science now? Schrefer interviews several young and mostly LGBTQ wildlife scientists, including Sidney Woodruff, a PhD researcher.

“I think sometimes as queer researchers,” Woodruff says, “in our lives, we hope to disprove heteronormative assumptions, but we can also perpetuate those same assumptions within our research. Like I have to keep in mind that if I’m researching sex and wildlife species, I’ll want it to be a certain way because of my own gender and sexual identity. It’s a lot of power that we have, but in our quest to find inaccuracies in previous research, we have to make sure we’re also being humble enough to know that we’re not always going to get the answer we want.”

Looks like science is in good hands.

Don't forget to share: