A survey last year of LGBTs in the workplace revealed that 28%, more than one in four, are totally closeted and not out to anyone in their lives. Forty-six percent are closeted at work.

German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs came out to his family in 1862 – 157 years ago, and a few years after that to the world.

In 1854, apparently his superiors for his civil service job as an assistant attorney for the Kingdom of Hanover became aware of his sexuality, and he resigned rather than be fired. He later worked as a freelance newspaper reporter and a personal secretary.

His first pamphlet on “Researches on the Riddle of ‘Man-Manly’ Love” was published in 1864 at his own expense under a pseudonym. From the series, he’s credited with being the first to formulate a “scientific theory” of homosexuality, one some others would come to share because they, too, couldn’t imagine anything other than variations of the binary of expectations of “male” and “female.” Ulrichs believed in a “third gender.”

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

He believed that men attracted to other men had been born with a “woman’s spirit” in a male body. Women attracted to other women had a “male spirit” in a female body. Anyone attracted to both men and women had some of both. As their feelings were inborn the state should not view their actions as criminal to be punished.

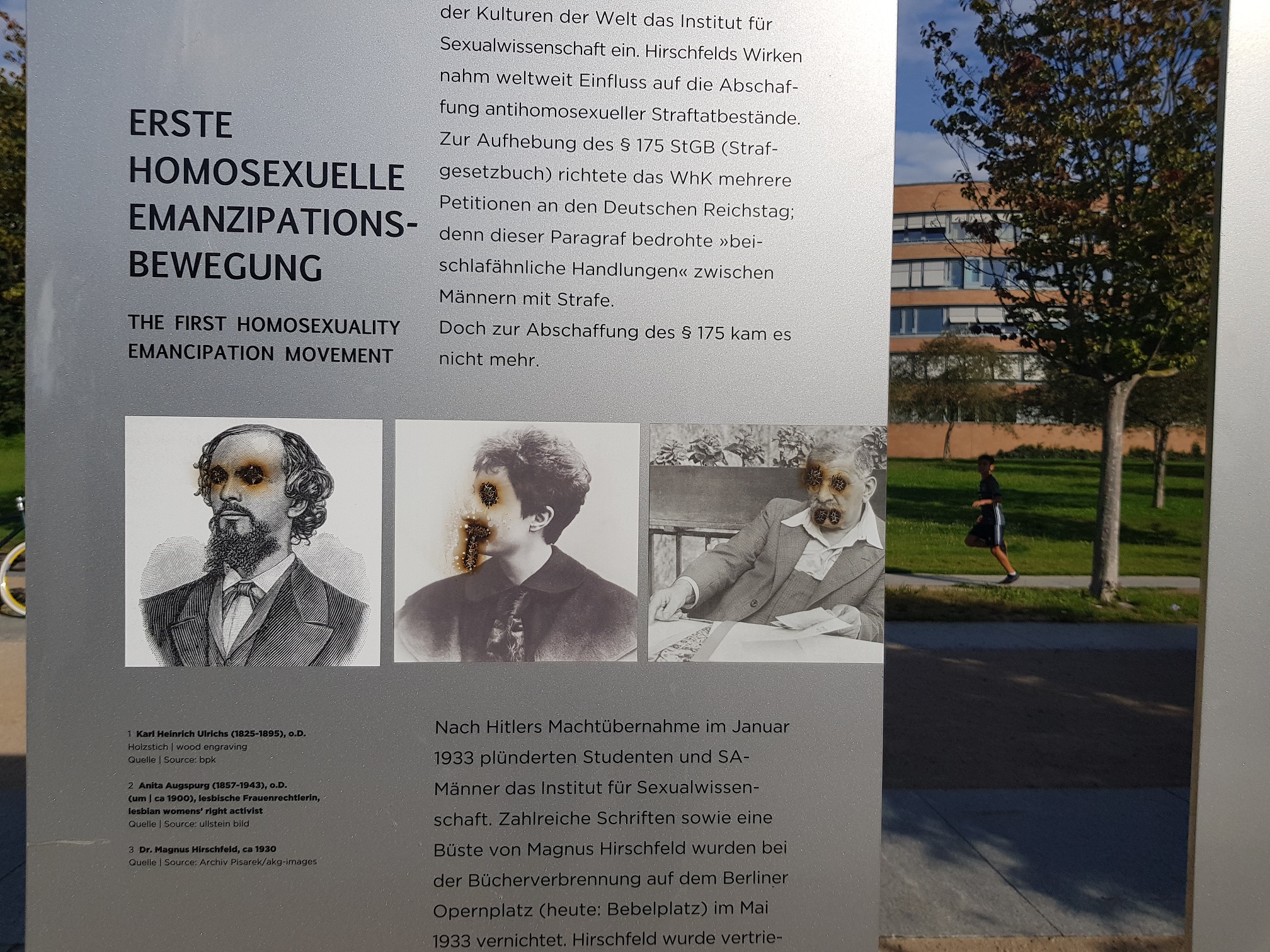

Because the Calla lily has both male and female flowers, six 13-foot tall Calla lilies, one for each of the basic colors of the rainbow flag, were installed in 2017 next to the memorial to the first homosexual emancipation movement along the banks of the Spree river in Berlin, Germany, featuring images of Ulrichs, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld who carried on some of Ulrichs’ belief in same-sex attraction being inborn, and lesbian feminist Anita Augspurg.

Contrary to oft-regurgitated “social constructionist” nonsense, a label for same-sex loving people doesn’t need to exist for same-sex loving people themselves to exist; but there have been words to describe same-sex loving people throughout time. The first was not “homosexual” coined in 1869 by Austrian writer Karl-Maria Kertbeny.

Ulrichs’ biographer Hubert Kennedy: “Ulrichs’ goal was to free people like himself from the legal, religious, and social condemnation of homosexual acts as unnatural. For this, he invented new terminology that would refer to the nature of the individual, and not to the acts performed.”

Because Ulrichs didn’t want to use any of the expressions in existence in his time, he coined the word “Urning” for men attracted to other men. Based upon a Greek myth, he used multiple variations for women attracted to other women including “Urningin.” He coined several other words for various kinds of same-sex attracted men, same-sex attracted women, and “Uranodioning” for those attracted to both men and women.

He also believed that two Urnings could live together in long term “love unions” similar to marriages between “real men” he called “Dionings” and women.

In 1865, the same year the American Civil War ended and Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, though nothing came of it, Ulrichs conceived of the first gay organization, an “Urnings union,” and sent a written proposal to the Congress of German Jurists for the repeal of laws against same sex acts. It was declared “not suitable to be considered by the Congress.”

Two years later, he was given permission to speak at one of their meetings in Munich but, ironically, was shouted down before he was able to make clear to all of the 500 lawyers and judges present — along with a Bavarian prince — what he was actually talking about.

After explaining that “a proposal” had been repressed, he was only able to refer to the “persecution of an innocent class of persons” who “in Germany is numbered in the thousands, a class of persons to which many of the greatest and noblest intellects of our and other nations have belonged … exposed to an undeserved legal persecution for no other reason than that mysteriously disposing creating nature has planted in them a sexual nature that is the opposite of that which is in general usual….” He also said that it was “a question…of damming a continuing flood of suicides, and that of the most shocking kind.”

Those yelling for him to stop speaking understood, however, and they didn’t want to give him any chance to make his case.

After his reference to “sexual nature,” he was actually asked by the Congress chairman to continue only in Latin so as not to offend less educated delicate ears. When asked to read the actual proposal he could only reply that it had been confiscated by the police months before.

One member from Dresden who had been involved in suppressing it wouldn’t explain any more when he rose to defend their rejection than, “[I]t is in contradiction to the current laws [and] offends modesty. Just by being read it would have aroused the indignation of this assembly! A blush would have come to our faces! And since we are to speak in Latin, I will tell you that it is of a sexual nature.”

Beginning with his sixth pamphlet, published in 1868, Ulrichs began to use his own name, confirming what his enemies in the Congress and elsewhere suspected as well as others aware of his multiple attempts to help various men charged with violating the laws against homosexual acts. Now it was undeniable, he was “one of them,” too.

The full extent of how much legal trouble he got into related to his Urnings crusade is unclear, but some of his pamphlets were confiscated by police and he was charged with violating statutes against degrading marriage or the family, defending illegal acts, and obscene speech. The judge found him innocent, and the pamphlets returned.

However, he was jailed twice for his vocal opposition to the invasion and annexation of Hanover by Prussia.

Surprisingly, in one of his pamphlets, Ulrichs outed “a distant cousin,” Johannes Diederich Sarnighausen, a minister and hymnologist who allegedly was forced to flee Germany after an accusation of sex with a soldier. Sarnighausen settled in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he took over publishing the very successful German language newspaper, Indiana Staatszeitung, was twice elected a state senator, and no hint of further scandal was found in contemporary portraits of Fort Wayne’s citizens or his 1901 obituary.

Three years after he was shouted down in the Congress, he published the world’s first gay periodical. His plan for several subsequent issues never came to fruition as he couldn’t find enough subscribers to support it financially. “The writings, it was the writings that brought me to beggary, since they brought no income.”

His last pamphlet was published in 1879, and the next year he moved to Italy where he changed his focus to promoting the Latin language, and his poverty worsened.

He continued to have admirers. Pioneering British gay liberationist John Addington Symonds visited him in Italy in 1891, and told fellow pioneer Edmund Carpenter in 1893 that, “He must be regarded as the real originator of a scientific handling of the phenomenon.” Both men translated some of Ulrichs’ poems about same-sex love into English.

By 1894, through a newspaper personal ad, there was evidence that his original pseudonym, “Numa,” had become a code word among gay men in Germany:

“young bicyclist, Christian, to twenty-four years, from a very good house, would join the same (foreigner) to undertake in August a nice bicycle trip to Tyrol. Desire very handsome appearance, distinguished manners, basically enthusiastic dis-position. Will answer only applications with photograph, which will be immediately returned. Write ‘Numa 77′ general delivery Bayreuth.”

Kennedy: “Ulrichs’s impact on sexology was more significant for directing medical researchers’ attention to the subject of homosexuality than for changing their view of it. Richard von Krafft-Ebing, for example, whose book Psychopathia sexualis (1886) established the medical view of homosexuality, was first interested in the subject by Ulrichs’s writings.” While Krafft-Ebing continued to believe homosexuality was a “sick, mostly hereditary de-generative condition” he also supported decriminalization.

Ulrichs died of a kidney ailment on July 14th, 1895. Two years later, often giving him credit for his unprecedented openness and activism, Hirschfeld founded the world’s first gay rights group in Berlin, the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, and, though he never came out publicly, created huge public support for decriminalization that came close to succeeding before being crushed by the Nazis.

While his scientific theories fell out of favor long ago, he continues to be honored for his courageous advocacy for legal equality. An international group dedicated to preserving Ulrich’s memory is planning a celebration next year in L’Aquila, Italy, of the 195th anniversary of his birth.

A number of cities in Germany have streets named for him along with a plaza in Munich. And the International Lesbian and Gay Law Association gives an award in his name.

Conversely, for the third year in a row the Berlin monument to the first gay emancipation movement has been vandalized.

Don't forget to share: