There’s something uniquely unsettling about taking cabs in foreign countries. Getting into a stranger’s car always puts you in a vulnerable position, but it’s even worse if you don’t speak the language and don’t know the city. And if you’re LGBTQ, and the driver starts asking personal questions, the tension ratchets up even faster.

Not long ago in rural Mexico, a cab driver asked if the two of us were brothers.

Related: Why are the major travel associations aligning themselves with anti-LGBT forces?

“No,” we said. “We’re, uh, just friends.”

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Hearing that, he eagerly suggested taking us to a brothel. But his English was limited, so he communicated this by taking his hands off the steering wheel and making the shape of a triangle while saying, “Pussy!” over and over.

Enlightened, he wasn’t.

For the past two years, we’ve lived as “digital nomads” – working remotely and living in different countries, usually for several months at a time. Naturally, we’ve taken countless cabs, rideshares, and tuk-tuks, in all kinds of situations. We’re currently in Tbilisi, Georgia. Thanks to the Greek Orthodox Church, it’s considered one of the most homophobic countries in Europe.

Last week Michael had to take a rideshare by himself late at night.

“What do you think of Georgia?” the driver asked him.

“I like it a lot,” Michael said. “It’s a beautiful country.”

“Are you here by yourself?”

Michael didn’t know what to say. It’s been decades since either of us lied about being gay. But the driver was a large, bearded man, and Michael was alone in a strange part of town. Could this driver be one of the nationalists who just the month before had marched around Tbilisi looking for members of Tbilisi Pride to attack?

Michael decided to dodge the question. “I’m here with a friend,” he said.

“Ah! Well, what do you think of Georgian woman?”

“Uhhhh, I’ve been really busy,” Michael said. “I haven’t met any.”

Thankfully, the ride ended a few moments later, and without an offer to find a prostitute. But it left Michael feeling crappy. He hated lying about being gay – it felt like a violation of his personal values. He hated assuming the driver was homophobic. And he’d hoped that being an out gay man to the average Georgian might make it just a tiny bit easier for Georgians to be out as well.

But personal safety always comes first. A gay friend of ours was assaulted outside of one of Tbilisi’s two gay nightclubs not long ago. And we’ve received some online harassment from anti-gay Georgians as well.

That said, another Georgian friend told us not to worry too much – that rideshare drivers were used to dealing with foreigners, and by now, they’d seen and heard it all.

Still, the issue seemed complicated

A week or so later, we hired a driver named Max to take us and some friends on a three-day trip to neighboring Armenia, which is even more homophobic. That meant we would spend almost seventy-two hours with our driver, since he’d have his meals with us and stay at the same hotel.

Plus, we’d all be crammed into his Honda Prius during the long drive.

Before leaving, we decided to be discreet about our relationship, because we didn’t know how he’d react: we didn’t want to be stuck in a car for three days with a homophobe. But honestly, we figured it probably wouldn’t even come up.

Alas, we figured wrong. Max’s second question to Michael was: “Are you married?”

“Uh, no,” Michael said.

“Never?” Max asked.

“Never,” Michael said, feeling extremely awkward again.

Things soon got more awkward still. Was Max wondering why the two of us were sharing a bed? It’s not unusual for straight men to share beds in this part of the world, but it probably is unusual for Western men to do so.

And then there was the casual nature of our relationship, and the many references our friends made to our being a couple. Once you’re out, it’s surprisingly difficult to go back into the closet.

Max wasn’t stupid. At some point, he must have realized we were gay, though he treated us no differently. But then on the last day as he drove us home, Max’s questions to Michael resumed.

“Do you own a house back in America?” he asked. “Where are you going next?”

Answering him without using “we” pronouns was getting seriously awkward.

We never did officially come out to him.

The following week, we considered hiring Max for another trip. He was a superb driver, which is not a small thing in this part of the world

That said, this time there would be no subterfuge. Michael sent him a text.

Hi Max,

Hope you made it home without any problems. Thanks again for a great trip. You’re a terrific guide. Brent and I are definitely thinking about the Kazbegi overnight, but before we pick out a date we wanted to check about something first.

I’m assuming at some point during our trip you realized Brent and I are gay and, in fact, married. We’ve actually been together for more than two decades. I didn’t tell you this right away because we’ve been advised that Georgia is a very traditional country and we didn’t want either you or ourselves to be uncomfortable spending three days together. That’s no good for anyone.

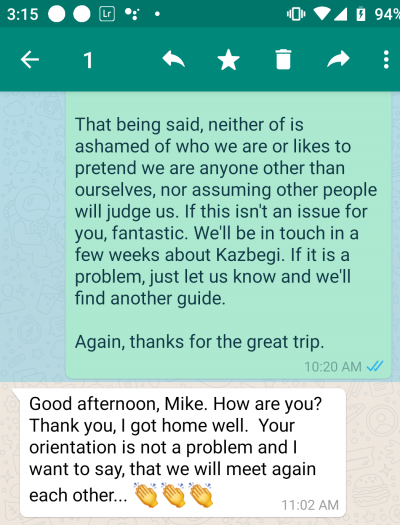

That being said, neither of is ashamed of who we are or likes to pretend we are anyone other than ourselves, nor assuming other people will judge us. If this isn’t an issue for you, fantastic. We’ll be in touch in a few weeks about Kazbegi. If it is a problem, just let us know and we’ll find another guide.

Again, thanks for the great trip.

Max responded very quickly:

Good afternoon, Mike. How are you? Thank you, I got home well. Your orientation is not a problem and I want to say, that we will meet again each other…

Maybe Max’s reaction solely had to do with the fact that by being accepting of us, he was going to earn another paycheck. Or maybe he really was fine with it.

It’s okay with us either way. Whether he approved or not, for three days, he’d had no choice but to get to know a gay couple, to see that we weren’t strange, exotic creatures; that, in fact, we were pretty decent guys who just want to live our lives. And maybe the next time he hears about LGBTQ Georgians fighting for their rights or being treated badly by their fellow countrymen, he’ll have a slightly different perspective on the issue.

Heck, he might even mention the two nice gay guys her drove around Armenia and Kazbegi.

And progress on LGBTQ issues in Georgia will inch forward a little bit.

Either way, the two of us won’t feel like we had to compromise a piece of ourselves.

Brent Hartinger is the author of the gay teen classic Geography Club, which was adapted as a feature film, and Michael Jensen is an author, editor, travel blogger, and columnist. Visit them at BrentAndMichaelAreGoingPlaces.com, or on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter.

Don't forget to share: