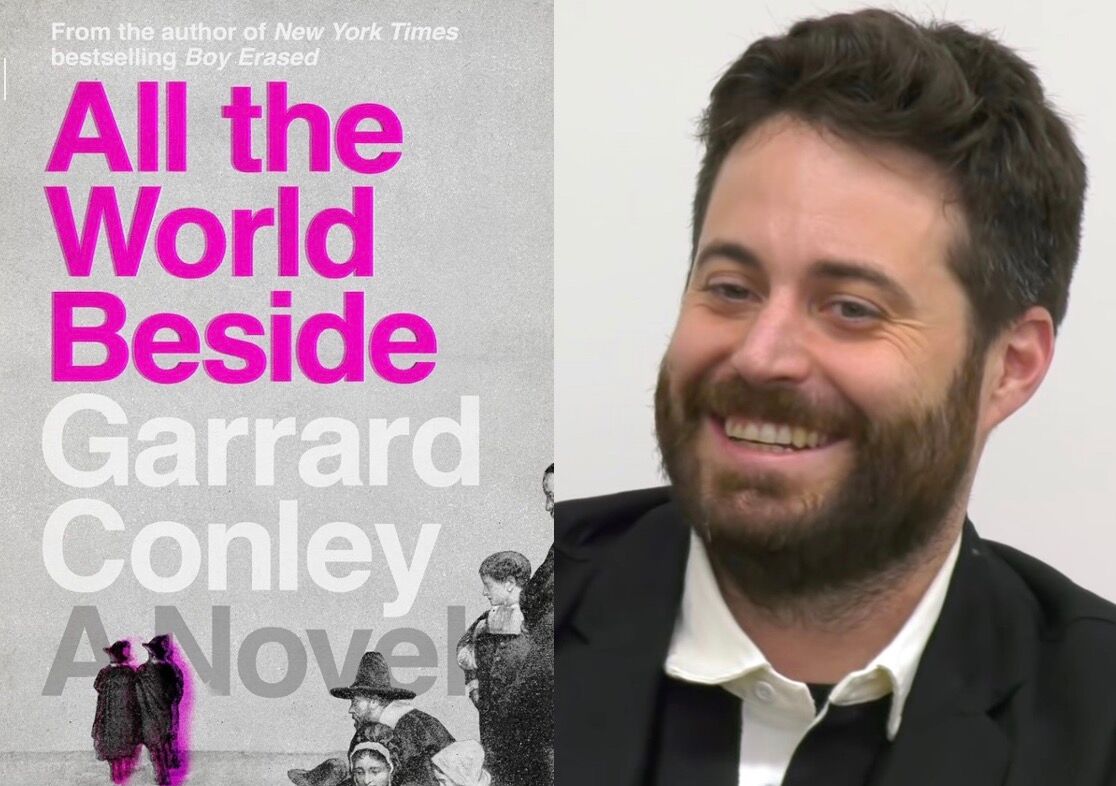

After the success of his debut memoir, Boy Erased, Garrard Conley felt pressure to follow up his bestselling memoir with a contemporary auto-fictional novel, as many of his contemporaries have done successfully.

But when his husband dared him to write about sexuality and religion in the 18th century, Conley began to work on All The World Beside, a queer love story centering on a minister living in 18th Century New England amid the backdrop of a theocratic society.

Related:

Almost all of 2023’s most challenged books were LGBTQ+

Several were also about people of color.

Conley told LGBTQ Nation that he wanted to write The Scarlet Letter with a queer spin, and his effortless ability to genre shift is evident from the very first page of this addictive historical thriller.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

LGBTQ NATION: Can you provide a bit of background on All the World Beside?

GARRARD CONLEY: This novel is a work of historical fiction. It takes place in 18th-century New England, and it follows a minister who falls in love with another man in his town. We see not only their challenges and joys, but we also see those challenges echoed in their families within the narrative. I’m calling it the queer Scarlet Letter.

I think that this book sort of is speaking to that reclamation that happens in The Scarlet Letter where this symbol of shame, you know, the A for adultery, becomes a symbol of beauty and something that is almost coveted by the people in the town because of the art that is employed with the letter. And so I think that that’s a big giant metaphor for pride. We take something that was a mark of shame and turn it into something joyous and beautiful. And so that’s kind of what I’m trying to do with this book.

Did contemporary shaming/cancel culture influence your writing?

I think that puritanism infects almost every part of our culture. And that’s certainly on the right, and it is sometimes on the left as well. So yeah, I think that there’s no way not to be in conversation with that somehow.

I think that with all of the anti-LGBTQ+ legislation today and all of the endless book bans, my book being one of them in multiple states, that’s definitely at the top of my mind. I think that puritanism, fundamentalism, whatever you want to call it, a black-and-white worldview that doesn’t allow for the human spirit in any way to thrive, is what I’m trying to capture in my work.

One of the reasons it was such a joy to write this book was that I didn’t have to use the labels that we use today. So I was able to just depict characters who we could read as gay or bisexual or trans or genderqueer, but they didn’t have that language for it at the time that I’m depicting. They had different words or words that try to encompass who they are, and I think what that taught me is that words can never fully encompass who a full human being is.

How did you approach writing about New England in the 18th century? What made you want to explore that period? How much research did it require?

It was my husband who actually challenged me, I guess about seven years ago, to write about queer puritans as a joke, to be like, you’ve got all this knowledge of the Bible from your father being a preacher, let’s see what comes out.

I resisted at first and laughed at it. And one of the reasons I laughed was that I saw how much research would have to be done, right? I have a master’s in 18th century specialization, and I had closely looked at gender and sexuality in the period, especially on the London stage. So I knew a little bit about that, and what I really knew was how much work it was going to be. So the book became a kind of part research project, part reclamation of sort of this idea of queer Christianity that I think I’d started to encounter when Boy Erased came out.

There were so many queer people that would come up to me and say, ‘Thank you for not attacking faith, thank you for not attacking my belief system, because I’m a queer Christian, I exist.” I wanted to honor that sort of possibility that faith and sexuality didn’t have to be at odds with one another. And in fact, there’s a long history of the two not being at odds in certain times and places – unfortunately not in this country very often.

Boy Erased was such a giant success within the nonfiction canon. How does it feel to transition to fiction?

It was all a seven-year process because I did a lot of research, but there was a lot of like, oh, is this the book that I’m going to write? So there were all these false starts. I think the reason for that is because I was always really intimidated by the idea of writing historical fiction and getting it right, so to speak. Not only did I have to do a lot of research on material culture and theory on sexuality throughout the centuries, but I also had to get a good grasp on how these people spoke.

Obviously, I’m writing for a contemporary audience. I’m not going to do everything in the 18th century. But I had to find some sort of amalgam of an 18th-century language and contemporary language. And what was most shocking to me was that you really only find that diaries stemmed from reported speech because letters were formal, and they were meant to be read aloud often.

They’re trying to show off their education in letters oftentimes, but whenever you read diaries, you can sometimes get reported speech, and I was shocked to see contractions and like, phrases that we would use today. And so that informed the way that I wrote the dialogue, because I was just like, Okay, well, they basically talked like us.

Are you a writer who has to write every day?

When I’m in the middle of a project, yes., I need to write every day, or at least every workday. I might take off on a Saturday or something. But I like to do that. I can’t say I have recently been writing that frequently. I’m looking forward to just going back to a project.

You obviously reject the idea of being pigeonholed to one genre. Do you think you’ll do something totally different next?

Yeah, totally. I mean, I think I’ll probably always write about religion and sexuality. But my next book, I believe, is going to be about televangelists, mostly in the 90s. I always just want to do something different. I know there’s a lot of pressure to write the sort of auto-fiction Arkansas coming-of-age novel.

When I presented [All the World Beside] to my agent and editor, they were like, okay, I guess we can do that. That’s what I learned. You have to tell people the kind of writer you are going to be and it’s really scary, of course.

What role does literature play in this era of book bans?

Well, I think literature is the place where we go when we want to see some of our own rigid beliefs questioned or challenged. Reading is how we make more room for possibility. And that that’s all I’m interested in. When I read I’m not interested in affirming my political beliefs or just like, candy. I don’t want that. I want something that challenges me, that makes me feel slightly uncomfortable and that does something new.

And you feel like studying theocracy is a helpful way to combat it?

I guess there’s a part of me that honors religious experience and faith. I don’t want to dismiss that at any point because we all cling to different things to survive, right? And some of them feel very real, and maybe they are, on the most essential level, very real. And so I guess I want to remain open to that while also criticizing the fundamentalist outcroppings of that right and I think that that’s just always been I’ve always just wanted freedom to think openly and talk openly and I think that that’s what I’ll always feel.