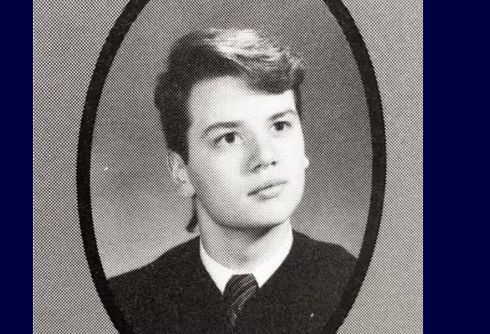

Look at this fancy little gentlethem! The bird whose eye-catching color story you are currently jealous of is a green honeycreeper (10/10 on that name, honestly). But this isn’t just any green honeycreeper. As you may have noticed, it is definitely green on one side, but blue on the other (talk about power clashing!).

Here’s the deal with our bold new feathered friend: According to Hamish Spencer, a zoologist and professor at the University of Otago in New Zealand, this particular green (and blue) honeycreeper is one of only two recorded examples of bilateral gynandromorphism in its species in more than 100 years.

Related:

Can animals be gay? Same-sex behavior is natural

Same-sex behaviors have been observed in over 1,500 animal species. It’s both fascinating and surprisingly controversial.

And what is bilateral gynandromorphism? Glad you asked! In a recent press release, Spencer explained that gynandromorphs are “animals with both male and female characteristics in a species that usually have separate sexes.” The phenomenon has mostly been observed in species that have pronounced sexual dimorphism: insects—especially butterflies—crustaceans, spiders, lizards, and rodents.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

“The phenomenon arises from an error during female cell division to produce an egg, followed by double-fertilization by two sperm,” Spender said.

In green honeycreepers, males have blue plumage while females are green. So, this little winged beauty is essentially half female and half male.

Spencer became aware of the bird while on vacation in Columbia, when amateur ornithologist John Murillo pointed it out. In a recent interview with Newsweek, Spencer explained that Murillo has seen this particular bird in the wild for over a year. Spencer and Murillo observed the bird, taking photos and videos, between October 2021 and June 2023. They recently published a report on their findings in the Journal of Field Ornithology.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, researchers reported that the bird “appeared to behave as any other member of its species, though it was more of a loner and did not display any courtship behavior or pairing.” They were unable to capture it, so it’s unknown whether its internal organs were split male-female similar to its plumage. But, they wrote in their report that “that would be expected” and they “strongly suspect it did not reproduce.”

As Smithsonian Magazine notes, studying gynandromorphs could help us understand how sex determination works. “Though researchers have known that chromosomes influence biological sex, much remains mysterious about the specific genes that control sexual development,” the publication explains. “Many biologists agree that dividing species into just the binary male and female is ‘overly simplistic,’ because a wide variety of traits typically considered male or female—such as chromosomes, sex organs and sex hormones—can be combined in different ways.”

“Many birdwatchers could go their whole lives and not see a bilateral gynandromorph in any species of bird,” Spencer said in the press release. “It is very striking, I was very privileged to see it.”