When I first started questioning my sexuality and identity, I didn’t feel butterflies. I didn’t feel excited or even the strong desire to understand more about these new feelings. I felt scared. Terrified even. I knew that even the first tendrils of these thoughts had the capability to unravel my entire life.

And unravel it they did. My past world had revolved closely around my community and my family. When you grow up in a Pakistani Muslim household as I did – and strictly Muslim at that – there is often a great reverence and respect placed upon relatives and elders, and also a strong emphasis placed on the importance of blood ties and family.

Related:

Queer men flocked to these secret 18th-century gay clubs to mingle, have sex, & mock straight people

Dozens of men came to Molly Houses to let loose, but their popularity would ultimately cause their downfall.

I grew up thinking of myself as a boy. In a world where men had certain duties and roles, my entire life and my outlook on the world was shaped by these men and the power they held.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Transness brought a real loneliness, and my world fell apart. My family withdrew from me, but I also shrank from their touch. Since then, I have found it hard to find community that I can really relate to.

So imagine my delight at finding Club Kali.

Creating magic

Club Kali emerged in the 90’s club scene in London, 1995 specifically, out of an intense need to develop an environment of freedom, dignity, and beautiful brown magic in the closeted doorways and rain-soaked paving stones of the city.

The struggle to build a space for Desi people, even without the added layers of queer identity, was intertwined with the tail end of 70s and 80s political movements for equality that were cloaked in political blackness and the strong stereotype of “queerness” being equated with whiteness.

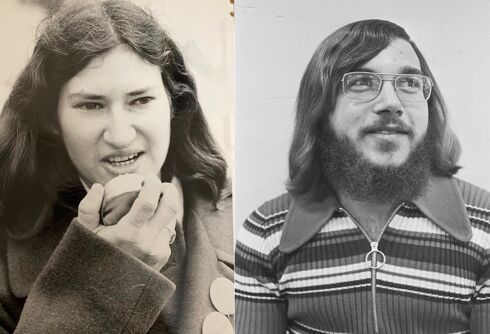

This struggle drew together two incredible Desi women – DJ Ritu and Rita.

Ritu and Rita met at the Shakti Disco, a venue in the London Lesbian & Gay Centre (LLGC) in Farringdon (a community center in London), where Ritu was the DJ. When Shakti closed, Ritu – by day a full-time youth worker – knew something was needed to replace one of the few scenes where intersectional Desi queer people could connect with a culture that often relied on the family love they had lost. For Rita – by day working with victims of Domestic Violence – her love of music was key to this future they wanted to build.

Ritu spoke with LGBTQ Nation about the first time she met Rita: “Rita walked into my DJ booth at the LLGC and asked for an Abba track to be played. I thought she was gorgeous. This thought was unrequited for about 3 years! But we became friends and then a couple. Eventually, we simply became business partners that created the two [of the] longest-running Asian club nights in the world. Club Kali since 1995 and our straight Bollywood club, Kuch Kuch Nights since 2000.”

Music and dance are strong reminders of the past, used as key tools in many cultures to teach the stories of ancestors and morality, but they are also important for self-reflection, self-love, and community care. Queer Desi communities called out for the magic of their culture to be intertwined with the newer aspects of London nightlife, in a time where community care was all but essential.

As Ritu explains, “Last century, being LGBTQ+ was an isolating, lonely, experience of feeling confused and ‘othered’. We had very few positive images of people like us in the media, particularly women. There were almost no South Asian role models – queer or non-queer. Everything associated with who we thought we were, was negative, and of course the intersectional racism, sexism, and homophobia was difficult. Eventually, I found a ‘gay scene’ in 1985, went on my first Pride march, and a few years later, became a founding member of a new South Asian LGBTQ organization, Shakti”.

DJ Ritu is a pioneer in this sense, and Rita is right up there with her. They dragged a biased world into a new age of music by never forgetting their roots but also never feeling the need to sacrifice all they had learned from their time in the UK music scene.

Ritu says that Kali itself was born specifically out of a need for safety, but also the need for a multicultural, multi-faith space that celebrated South Asian music. She says as a DJ, her magic is in the bringing together of diverse cultures through the power and joy of music, culminating on the dance floor. Through her work with Club Kali and her many other venues, she has provided a proper performance space for new artists and drag acts, and even hosted high-profile Brit Asian stars like Rishi Rich, Juggy D, and Jay Sean.

Pushing boundaries, fighting hate

To take it upon yourself to walk a path so hard is awe-inspiring, but unfortunately very common within the Desi Queer community. Many of us even now are forced, through the “othering” of ourselves as individuals and as a community, to walk alone. And while that is changing, I was keen to ask Ritu, along with Club Kali’s Community Engagement Officer Sakib Khan, what they think of the evolving world, and if they think we are on a track to more freedom and autonomy for queer Desi youth.

Ritu sees a bright future ahead, stating that Club Kali and its members and team, trailblazed and created new pathways for so many others to follow. She says that as soon as Kali was held up as a baton for others to see, many new and similar clubs opened. She spoke warmly of Zindagi – a club founded in 2003 for queer people in Manchester, that plays a colorful mix of the latest Bhangra, Bollywood tunes, Arabic music, RnB, HipHop and Dance, which she says is “furthering the boundary of clubbing.” She also praised the acclaimed Saathi club night in Birmingham. “Authenticity is key,” she said, “It must come from the heart.”

Sakib agrees, saying: “There are more events now than when Kali started, nightlife has changed a great deal in the 28 years since Kali began and there is greater visibility of LGBTQ+ people of color and from the South Asian diaspora, which is wonderful to see. Also, the change in legislation across the globe, particularly in India, has begun to shift attitudes. People have digital channels as a way of connecting and finding community. All of these are positives and with each generation comes a change in attitude”.

So we’re going strong, and now more than ever, with dangerous legislation on trans people finding its way into politics around the world, a space of safety and community for marginalized queer people is desperately needed. I pointed this out to Ritu, emphasizing my anger and pain as a generation of trans youth building our own new worlds, and she agreed strongly that while things are looking up in many areas, a huge push overall is needed.

“I wish we could do more… Because there’s such a huge need for it. But sadly, no – there aren’t enough spaces for queer Desi youth being made. Club Kali is limited in how much help and support we can offer to people at the moment. There certainly does need to be more funding for specialist organizations that can offer other services”.

Even so, it’s inspiring to see such strong figures exist in a world I thought I would never have and to see how much love and strength they have cultivated and nurtured for our community. Club Kali was established to offer shelter, and it would seem – through incredible platforms in dance, performance art, music, and even film – that it has developed into a godmother of the queer Desi clubbing scene.