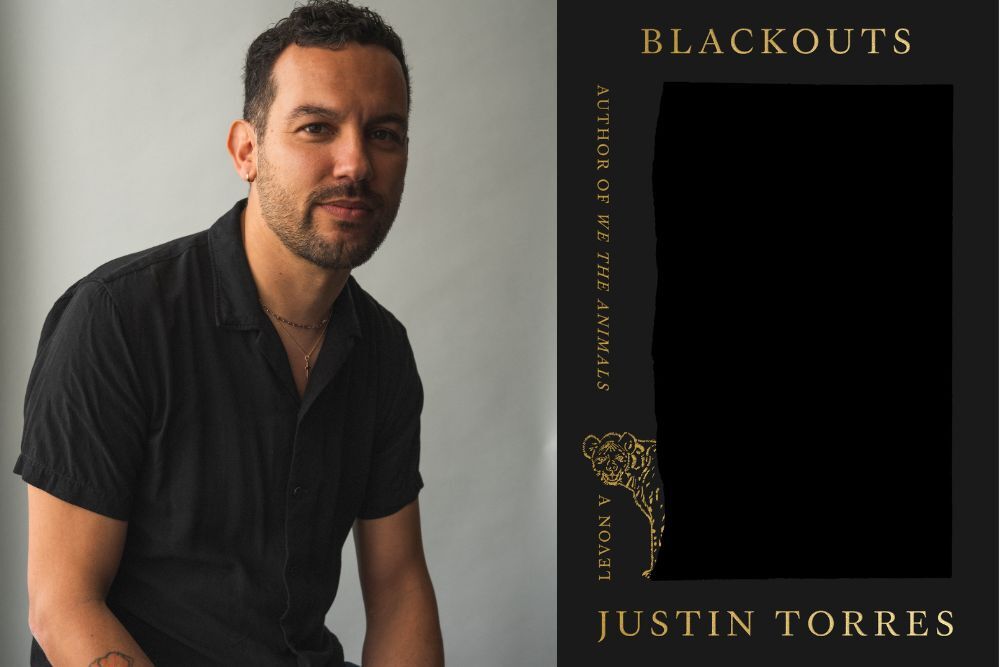

Justin Torres writes about people on the margins, people like him: queer, bi-racial, outsiders searching for their place in culture, society, and family. The youngest son of a white mother and a father of Puerto Rican descent, his 2011 debut novel, We the Animals, drew heavily on his experience growing up in Upstate New York.

Similarly, his new novel, Blackouts, centers on a young gay man searching for a better understanding of both his queer and Puerto Rican heritage. Finding himself at a sort of crossroads, the unnamed narrator turns to an elderly queer mentor, Juan Gay, and the two exchange stories in an effort to illuminate both their own lives and the stories behind the heavily redacted pages of a real study of homosexuality published in the 1940s.

Related:

“Aristotle & Dante” is groundbreaking in a world that lacks queer Hispanic role models

As a closeted gay Mexican, author Benjamin Alire Sáenz felt like he didn’t fit in. His experience represents that of countless queer Hispanics.

The novel, which was announced as a finalist for this year’s National Book Award for fiction just last week, weaves together forgotten LGBTQ+ history with the stories of its fictional main characters to create a uniquely inventive, profoundly queer, and very timely examination of the ways marginalized people often have to uncover our own stories and culture in the face of societal erasure.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Torres spoke to LGBTQ Nation about Blackouts, the real people who inspired it, and how his own queer and Puerto Rican heritage influence his work.

LGBTQ Nation: Blackouts was just announced as a finalist for the National Book Award, so congratulations. What’s it like to have the novel recognized like that before most people have even read it?

Justin Torres: It’s a dream come true. I was so nervous about this book. It’s a kind of challenging, slightly experimental book — or maybe very experimental. So, I just didn’t know how it would be received, and it just… All of that anxiety, I feel enormous relief and gratitude.

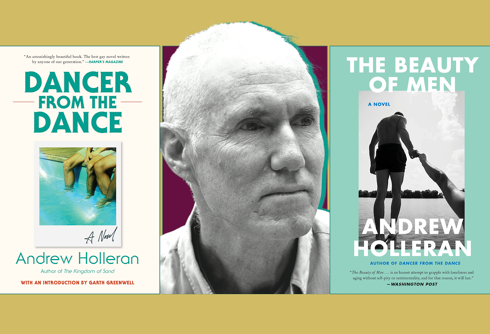

At the center of the novel is this real book, Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns. How did you first learn about that and why did you want to build a story around it?

JT: I was working at a bookstore called Modern Times in San Francisco. It doesn’t exist anymore, but it was a new and used bookstore. Somebody brought in a box of books to donate, and in the box were all of these texts that were familiar to me — these pre-Stonewall, pivotal gay novels: The Well of Loneliness, Jean Genet, all these things that I knew were touchstones to the queer community — and then this medical book called Sex Variants.

It was so different from everything else in the box. I opened it, and there were these photos of people with their faces blurred and there’s drawings of people’s anatomy — it’s a really intense read. There’s a lot of pathological language about homosexuality as a social disease. But also, the testimonies, the kind of first-person testimonies, the vernacular, the way people talked in the 1930s and described their queer lives and queer communities was so rich, and it was so clear that somebody had transcribed these with real care. So, I was like, “What’s the story of this study?” And I started doing some research.

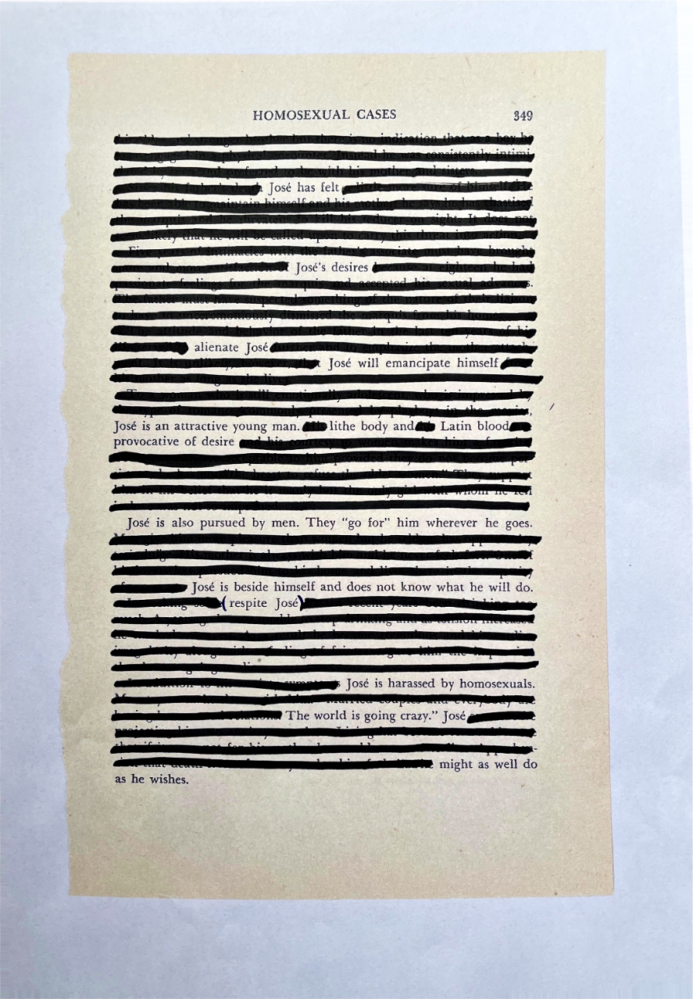

That’s not unlike the way that the characters in the novel find the book, but their copy of Sex Variants is largely redacted, leaving just bits and pieces of the participants’ stories. Where did that idea come from?

JT: My original impulse was to write the stories the way I feel they should have been written, rather than in this kind of pathological medical language, to treat these people more like people and develop them as fuller characters. It’s a kind of fantastical way of engaging with the past and with queer history.

And I realized as I was trying to do that, it felt really false, and what I had was this study of deviance. I kind of wanted to acknowledge the historical erasure of these people. I kind of wanted to acknowledge that this is our history. It can be really painful to look at these documents, but also you can find out quite a lot.

One day, I just photocopied a bunch of pages and started blacking out the stuff I didn’t like.

You did the redactions for the images in the book yourself?

JT: I did all that. And then, instead of just blacking out stuff I didn’t like, I was like, “Actually, what if I tried to make some kind of poetry out of this?” A third interpretation, a third overlay. These people came in and gave their testimony, somebody put a lot of pathological language on top of it, and then I’m doing something else with it. So, it’s like a third iteration rather than some kind of recuperative act.

And from that, where did the characters of Juan Gay and the narrator come from?

JT: The character who narrates the story is a young man in his late 20s and he is kind of a persona that I developed. I write a lot of fiction from personal experience, for sure; a lot of authors do. I developed this character that I feel like I know really well, but who is ultimately different from me.

And Juan, I would say, is an amalgamation of a lot of people that I’ve known in my life: queer mentors and elders and people that are just incredibly smart and patient with me. Sometimes in your life, you meet somebody that’s willing to teach you about both yourself and the world — that maybe some of the things that you think are your problems alone, other people have thought about in big, philosophical ways throughout history, and “How can I connect you to the literary world?”

I’ve been very fortunate in that I’ve had these kind of mentors in my own life at pivotal moments when I was really down or lost or something, and they were like, “Why don’t you read this?” So, that’s kind of what’s going on with Juan.

The novel is also largely built around an elder gay man and a younger gay man exchanging stories. We talk about gay culture, which of course is a real thing. But it’s unique, I think, because it doesn’t get passed down to younger generations the same way that most cultures do. Most of us are born into “straight” families, so there’s not really the same mechanism of gay elders passing down our histories to younger generations. Was that something you were thinking about while writing Blackouts?

JT: I was thinking about it massively. You can go back to ancient Greece and the entire idea of a Socratic dialogue is the older wise man in conversation with youth — and often a beautiful youth. And there’s something homoerotic in that exchange that Plato writes about. So, I was thinking about it very deliberately and with a lot of intention.

I wanted to highlight exactly what you described: this very unique way in which it is necessary to seek out your ancestors and inheritance. It’s not a given. It doesn’t happen organically or naturally within the familial unit that you’re just around grandparents and you’re around elders — it’s not built in. At a certain point, if you want that kind of intergenerational dialogue, you have to seek it out and find it or be lucky enough that somebody seeks you out. I think it’s a really important and dynamic aspect of queer culture.

Blackouts is particularly timely in that it is about an effort to kind of excavate a collection of queer histories that has been obscured. I feel like that sort of echoes efforts going on right now to ban stories of queer lives alongside the history of racism in the U.S. in schools and libraries. How much of that was going on when you were writing the book, and what is it like releasing this story into the world in that context?

JT: It’s kind of coincidental that here I am writing this book about redaction and erasure, and suddenly the far-right radicals have decided to latch onto book banning as the next front in the culture war. I didn’t anticipate that! But I think what I was responding to was a certain kind of self-censorship that was happening within the queer community, a certain kind of respectability politics.

There are a lot of penises in this book — pictures of penises. There’s sex in the book. There are drawings of vulvas. The relationship between sex and sexuality and queerness itself and queer culture is something that I think I wanted to be really explicit about. It’s not that this book isn’t respectable. I just got nominated for a fancy award! But it’s not aiming for a certain kind of respectability.

And I think what’s interesting about this moment is that the books that are getting banned are, like, children’s books about penguins! It proves the fact that there’s no point in trying to do anything that will appease these people, right? There’s no appeasing them.

Another coincidence: Children’s books and the two real-life queer women who wrote and illustrated them are prominent characters in Blackouts.

JT: So, that’s Zhenya Gay, and she along with Jan Gay, who was instrumental to the Sex Variants studies, they both changed their names at the same moment — I assume it was some kind of marriage, right? They were a couple, they both changed their last name to Gay, which at the time was still pretty underground. It was a clear signal to anybody in the community.

But both Jan and Zhenya — “Jan” could be read on the page as “Yhan,” which was a very common Scandinavian name at the time, and “Zhenya” is a gender-ambiguous name in Russian. So, they did this kind of bold renaming of themselves. When you read their names on the covers of these children’s books — they wrote them together and Zhenya did the illustrations — you don’t know their relationship. It doesn’t signify in an explicit way. Here’s two people with the same last name. Are they two men? Are they two women? Are they married? And I think that’s really fascinating.

And the books themselves, when I read them, I’m like, “This is so queer!” A lot of them are about a very effeminate young boy, usually a boy of color, who is gently moving through the world. There’s one that in the novel gets read as being all about a gay bar. This “watering hole” — it’s a literal watering hole in the savannah. I think reading itself is so essential to queer identity: the sense of reading and being read, but also situations, being able to read other people, reading for codes, reading for cues — that’s a huge theme in the book as well.

A section of the book also deals with something called “Puerto Rican Syndrome.” Can you explain what that was and why you wanted to kind of twin that to the Sex Variants study and your characters’ experiences of? Would you characterize it as a mental illness?

JT: The two main characters meet in a mental hospital. They meet when the younger one is about to turn 18, and he’s been institutionalized very much against his will, and Juan is there. Juan’s kind of somebody who’s just in and out of mental institutions a lot. You get the sense that it’s a kind of depressive position that he has in the world.

The Puerto Rican Syndrome is this diagnosis that existed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. So much of the writing on homosexuality in early sexology is tied up with ideas of disease: Diseased minds, diseased bodies. It’s just a really big part of how the understanding of homosexuality as an identity position comes into the world. I think that the Puerto Rican Syndrome diagnosis comes from a very similar place.

It appears suddenly on the radar of these white American doctors when there’s this huge influx of Puerto Ricans arriving in New York. It’s this big wave of migration that happens in the ’50s. So, I think it’s no accident that suddenly there are all these people that are quote-unquote “hyper-visible” — and yet they’re also not visible in any of the mechanisms of power — and they’re getting pathologized; they’re being looked at through this lens.

So, I think there’s something really interesting about the fact that being queer for so long was a mental illness by definition, and being Puerto Rican was! It’s wild! I mean, eventually these things get changed. But I think it’s really reflective of how the dominant culture processes its own hysteria around that which is unfamiliar.

LGBTQ NATION: Like your main characters in both Blackouts and We the Animals, your mother is white and your father’s family is from Puerto Rico. I certainly don’t want to fall into the trap of assuming that these characters are based on you. But how has your experience of your biracial identity influenced your work?

JT: I think that I’m always gonna write characters who are very much interested in the themes of queerness, racial identity, racism, homophobia; that are very much interested in and have been affected by the kind of endless class warfare that is being waged on poor and working-class people — capitalism itself and the brutality of capitalism.

The things that I didn’t have political language for when I was growing up, but that affected me very much, and I knew were affecting me, but I didn’t quite know how to process and understand. I felt a lot of stigma, I felt a lot of shame, I felt a lot of rage, and I didn’t necessarily have the political language for understanding or processing that. I think all of my work is always going to be interested in characters who are dealing with that and maybe do find ways of kind of metabolizing that and making connections to literature and history.

I very much write from the margins. This is one of the things that attracts the narrator to Juan. Juan was born in Puerto Rico. He speaks Spanish. There’s some sense of authenticity that the narrator is hoping to get from Juan. But, of course, Juan doesn’t give it. One of the things I think Blackouts is about is that you actually just find a lot of gaps. You find a lot of ephemera.

In Blackouts, Juan criticizes the narrator a few times for not speaking Spanish — or not being as fluent as Juan thinks he should be. What were you trying to convey about the narrator’s sense of his identity? Is that something reflected in your own life?

JT: Again, I think I’m really interested in generational dialogues, dialogues across generations. We talked about talking to a queer elder from another generation, and the ways in which they might be, like, bemused or confused about the ways that people are identifying now. And also sometimes horrified that people don’t know their own history. And I think the same thing happens all the time with children of migrants.

I think with Puerto Ricans in particular, those who are third generation who don’t speak Spanish, it’s not shaming or terrible, but it’s a constant refrain: “Why don’t you speak Spanish? Why isn’t your Spanish better?” It’s an interest in that dynamic, again, because my father, the stigma and shame was so intense. His way of dealing with that, I think, was to really, really, not just speak English very well — because he did — but also to understand whiteness.

My grandmother, she didn’t speak English, and I think he saw that as a source of a lot of discrimination and difficulty that she had to deal with. And he wanted different things for us. And then the culture changes, and nowadays I think people are emphasizing whatever your heritage is: Embrace your heritage! But it definitely wasn’t what was going on for my father in the ’70s and ’80s. And that’s not to say other Puerto Ricans weren’t; There was definitely a movement of Puerto Ricans who were very interested in preserving their heritage.

You’ve said in other interviews that you grew up in a very white town in central New York. How did you then and how do you still stay connected to your Puerto Rican heritage?

JT: One of the things that my book is about is somebody who is actively seeking out a connection to lineages — queer lineages and Puerto Rican lineage, whatever it means to be Latino or Latinx or Latina — who is actively seeking out what is there. I think the answer that the book gives and that Juan gives the narrator is: Literature is always available to you.

You’ve got to know literature. So, Juan teases him about not knowing enough about his quote-unquote “forefathers,” right? And he points to people like Manuel Puig and Miguel Piñero, who was Puerto Rican — Puig wasn’t. He talks about Jesús Colón, another incredibly important Puerto Rican writer who was one of the first people to write about the Latino experience, Puerto Rican experience, especially the Afro-Latino experience.

So, one of the things that happened to me — with We the Animals, I wrote this book and it’s set in Upstate New York. It’s very much about this experience of alienation. It’s very foregrounded. And then people would be like, “Tell me about Puerto Rican heritage!” And I’d be like, “I can tell you about alienation and feeling very much on the periphery and disconnection.” That’s what I can tell you about and that’s what the book is going to tell you about.

I think that’s what Blackouts is investigating as well. But the book purposefully brings in all of these other literary traditions as a way of being like, there’s disconnection, but there’s also so much potential for connection.