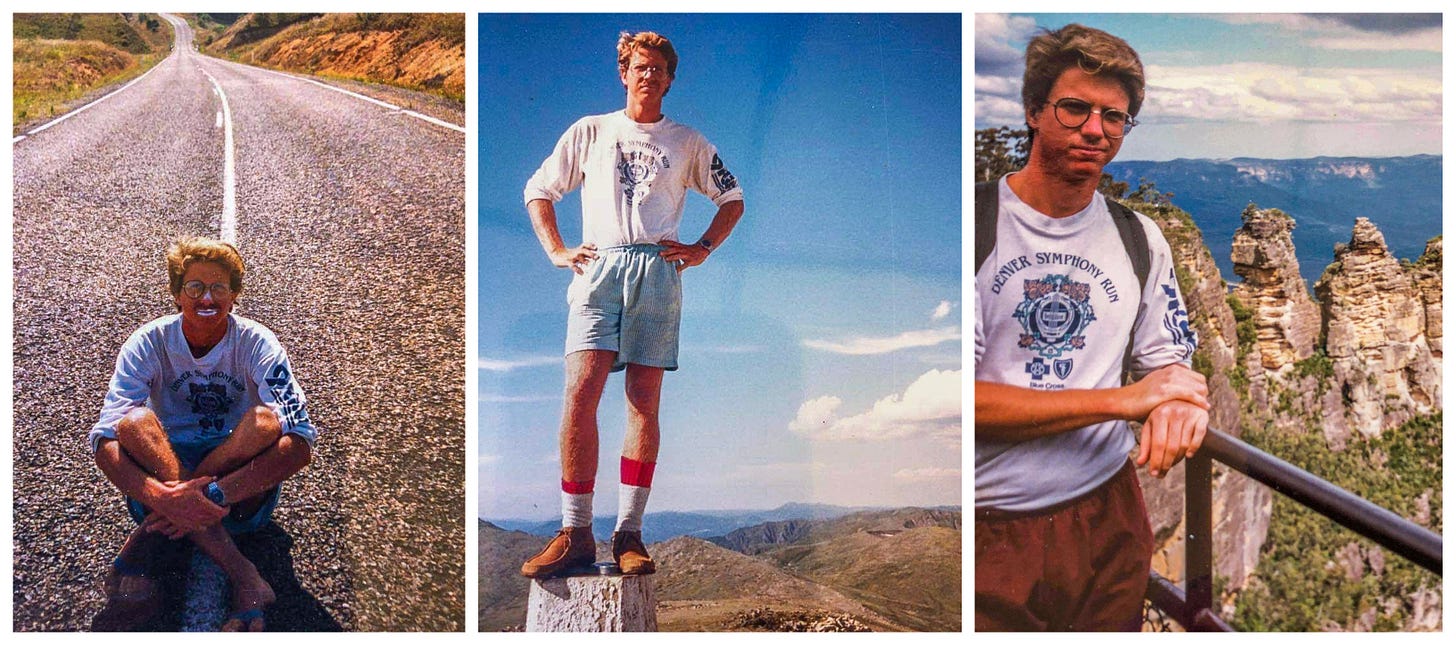

November, 1987

My college buddy John and I stood on the beach in a hidden cove in Southern Australia. Behind us, unscalable cliffs stretched straight up to the Great Ocean Road — some seventy meters (230 feet) above us.

Meanwhile, in front of us, huge waves crashed against the shore — also unpassable, and that’s not even counting the freezing waters of the Southern Ocean that stretched all of the way to Antarctica.

Related:

How tattoos helped me reclaim the power of my queer & trans body

For so many queer and trans folks, tattoos keep us alive.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

I was trapped.

Okay, I wasn’t trapped. We could crawl back through the difficult, narrow passageway carved through the rock that had brought John and me here in the first place.

But we’d come here for a reason, and we hadn’t yet done what we’d intended to do.

It was just John and me here at the bottom of Australia, and it felt as if the entire continent loomed above us like a great weight. We’d spent the past month hitchhiking from Sydney down to the Twelve Apostles, a famous rock formation just off the coast of Victoria.

But I was trapped in other ways. Tomorrow, we headed north again, a trip I didn’t want to make — because it meant doing something I really didn’t want to do.

I was twenty-four years old, and I had been hired as a tour guide at the U.S Pavilion at the upcoming World Expo in Brisbane. Out of thousands of applicants, only forty of us had been chosen. Somehow that had included me.

I knew it was an amazing job — a fantastic opportunity.

But I was an introvert, terrified of public speaking. I had only applied out of desperation, because I was looking for a legal way to work in the country. I had been a high school exchange student here six years earlier, and it had changed me for the better. I’d loved it so much that I’d wanted to come back.

I hadn’t really expected I’d be chosen, and now I didn’t know how to deal with my looming terror.

Plus, the job would only last four months, and I’d then have to figure out the rest of my life. I’d recently graduated from college with a degree in business — a major I’d only chosen because of pressure from my dad. I wanted to be a writer, but I hadn’t a clue how to go about it — or if I even had the talent or drive to pull it off.

And something else was just starting to form in the back of my mind: Was I gay?

That freezing ocean and those sheer cliffs seemed like nothing compared to the way I felt trapped by the choices I had already made — and the ones I had still to make.

John and I had camped at this particular beach to see the area’s “fairy penguins” — several hundred of them that inhabited the colony just behind us in the dunes.

The only reason we knew about the penguins and their colony was because of the local fisherman we’d met in a town up on the Great Ocean Road.

“You guys want to sleep somewhere way more interesting than a hostel?” he’d said. “Have yourselves a real adventure?”

John and I looked at each other. We’d left Sydney a month earlier and had hitchhiked our way down the coast into Victoria. We told ourselves we were looking for adventure, but the truth is, we’d played it fairly safe so far.

“Depends,” I said to the man. “Sleep where?”

“With the fairy penguins!” He laughed. “I bet you didn’t see that coming.”

“That sounds pretty amazing,” I said. John gave me a look that said he agreed.

“It’s bloody amazing, mate. Now here’s how you get there.” He proceeded to explain that a few kilometers outside of town, we’d find a set of stairs carved into the sheer cliff face.

“But be careful going down,” he said. “Those stairs can be damned slick and a bit scary. After you’re on the beach below, look for a narrow opening hidden in the rocks at the very end. Once you spot it, you’ll have to crawl through. Halfway through you’ll come to a metal gate that keeps foxes out. Make sure you close that behind you! Once you reach the other side, you’ll have the whole beach to yourself. The penguins have a big colony down there.”

Experiences like this were exactly the reason I’d come back to Australia — to challenge myself and overcome obstacles. I was desperately trying to avoid the boring life that had been mapped out for me.

And fairy penguins? I really wanted to see those!

The steps were as steep as promised, and, yup, they were slick with spray from the ocean. There was no guardrail, and they descended almost straight down — even more difficult with two heavy packs. More than once, I considered turning back.

Then there was crawling through that narrow tunnel at the bottom — so narrow we’d had to drag our packs behind us. It was a good thing I’m not (too) claustrophobic.

And even if the metal gate was only meant to keep out foxes, pushing through it felt a bit like entering a forbidden world.

But John and I had made it, and now we sat on the beach, waiting for the penguins to appear.

It’s true, I’d lived in Australia before, and it had genuinely changed me. I’d lost weight, started standing up to my parents, and begun to take charge of my life.

But now six years later, I had lost my way again. Why had I let my father pressure me into that business degree anyway?

That’s the last time I let anyone else make a decision for me, I’d thought at the time.

Now on the other side of college, that felt easier said than done.

A seagull floated down from above, alighting on the crashing surf as if it were the easiest thing in the world. Each time a wave started to break, it simply flapped its wings, flew backward a dozen meters, found a new spot, and settled down again.

I envied the ease with which it moved through the world. If only I could navigate my life so easily.

We could hear the penguins, but not see them. Their colony was behind a nearby dune. Half of the adults stayed behind with their chicks, and the other half swam out to sea during the day to fish.

John and I weren’t irresponsible enough to disrupt the colony itself. Instead, we waited on the beach to see the return of the penguins in the sea.

The sun fell toward the water, its rays steadily lengthening, illuminating the spray off the crashing surf.

Once the sun set, the penguins should start to return.

Fairy penguins — the smallest of all the penguins — are amazing creatures. They only weigh a kilogram and a half (three pounds ) and stand no more than forty-one centimeters (sixteen inches) tall. But every morning before dawn, half the birds in this colony plunged into freezing water and swam a dozen or more kilometers out to sea to hunt for fish.

Out there, they braved the ocean itself, not to mention all the animals that preyed on them: gulls, leopard seals, killer whales, sharks, and sea eagles. Then every day at dusk, they somehow navigated their way back through that dark, immense sea to this tiny beach where their chicks and mates waited for them.

That night, I waited for them as well.

I remembered something else the fisherman had told John and me: “If the waves are too big, sometimes they don’t make it home at all.”

Come on, little guys, I thought. You can do it.

As dusk crept closer, I watched the surf crash into one of the rocky Apostles standing just offshore.

The Apostles, limestone stacks that were millions of years old, had withstood eons of battering by the ocean. Looking at this one, jutting up out of the water, stalwartly facing the ceaseless waves, I tried to imagine myself facing my future like that Apostle — steadfast, unyielding, and unafraid of the world I faced.

I didn’t feel nearly that strong.

Or did I? Looking back now, while I might not have been as stalwart as those Apostles, I saw I had made some difficult decisions. After all, I’d found a creative way to get myself back to Australia; I’d somehow managed to get the folks at the U.S. Pavilion to pick me.

I’d also stood up to my parents.

“You’ve no idea what a stupid mistake you’re making,” my father had said. “These are important years for your banking career!”

“I don’t want a career in banking,” I’d said. “Or any kind of business.”

He’d thrown up his hands. “Do what you want then. One day, you’ll see your old man was a lot smarter than you thought.” After that, he’d literally refused to speak to me.

My mother used a different tactic.

“You need to know that every day you’re gone is going to be hell on me,” she’d told me before I left. “I’m going to be terrified something is going to happen to you.”

Right before I boarded my flight, she’d clutched my arm and said, “You’ve no idea how hard this is going to be for me.”

It hadn’t been easy, standing up to them and deciding I wasn’t responsible for their fears. But I’d done it. Even so, there was still so much more I needed to do.

The waves kept crashing against the Apostles, and the penguins still hadn’t returned.

It felt like the odds were against us both.

The sun dipped below the southern horizon, each crash of the waves seeming to wash away a bit more of the light.

The wind was dying down, and we could smell the colony of penguins now — not pleasant at all. Regurgitated fish and a healthy dose of ammonia. My eyes watered, and I breathed through my mouth.

“Shouldn’t they be here by now?” I asked John, anxious for their return. “The fisherman said they came back to shore when the sun set.”

“He said they would come after the sun set,” said John.

“Maybe we’re frightening them. Maybe we should move farther back.”

By now, John was used to my being a bit of a worrywart. “It’s fine,” he said. “We’re exactly where he told us to be.”

I knew he was right, but I was still worried. When you’re as small as a fairy penguin, the world must be a huge scary place.

“There!” said John, grabbing my arm and pointing.

I strained to see what he had spotted. We were deep into twilight, and it was hard to make out much more than the white foam of the waves.

“I don’t see anything,” I said.

“It’s gone,” said John.

Had he imagined it? What if the waves were too high? What if John and I really were too close to the colony?

Another wave dashed against the sand. When it retreated, three tiny figures appeared as if by magic.

Their heads swiveled back and forth, assessing for danger before the next wave snatched them away again.

Several more waves rolled ashore without any more penguins. Had they decided John and I were dangerous?

Another wave hit the sand, all white foam and spray flying up into the air.

Now dozens of penguins remained. For a moment, they stood huddled together, their white bellies gleaming in the dark, their heads darting back and forth assessing for danger one final time.

Another wave rolled ashore, dozens more penguins now on the beach.

“That’s got to be a hundred of them,” I whispered to John. “Maybe more!”

As if an order had been given, the penguins surged up the beach as one. Their heads were thrust forward, their wings outstretched as they rushed back to their nests.

And, yes, their waddling was comical, but there was such determination in them that rather than laughter, I felt nothing but admiration. Twelve hours earlier, these tiny birds had plunged into the ocean, swum far out to sea, hunted all day among sharks and seals, and then swum all of the way back where they had to brave waves that could dash them against the rocks.

But they’d done it.

Before I knew it, they were back in their colony — safe.

The air erupted with grunts and hoots as each penguin found its mate and chicks. The noise was surprisingly loud, but it sounded both happy and relieved.

John and I look at each other. It might have been dark but we could see each other’s smiles.

Not long after, John and I laid out in our sleeping bags. Behind us in the dunes, the penguins chattered away, deep into the night.

But John and I were silent, thinking.

Earlier in the day, I’d been so afraid of the future — of my job in Brisbane and the future beyond. It all felt too hard and scary.

But now I could only think about those fairy penguins — how they swam far out to sea day after day and yet somehow found their way back.

If they can do that, I thought, maybe I can find my way too.

Note: I have been purposefully vague about the location of this cove. It is now closed to the public, and even at the time, the surf and the stairs were very dangerous. Several years ago, two people came here to swim and found themselves in trouble, and two rescue workers died saving them.

Additionally, getting this close to wildlife is never okay, and I truly wish my foolish twenty-four-year-old self had known better.

Michael Jensen is an author, editor, and one half of Brent and Michael Are Going Places, a couple of traveling gay digital nomads. Subscribe to their free travel newsletter here.