In their new book, Fair Play, author Katie Barnes writes that “sports have become a flash point for a broader conversation about transgender people on the heels of more visibility of that community.” Since 2020, scores of anti-trans bills have been introduced in state houses across the country, many banning transgender girls and women from participating in women’s sports at the high school and collegiate levels. According to the Movement Advancement Project, 23 U.S. states have passed such laws, and groups like Save Women’s Sports have characterized trans women’s inclusion as an existential threat to the very concept of women’s sports.

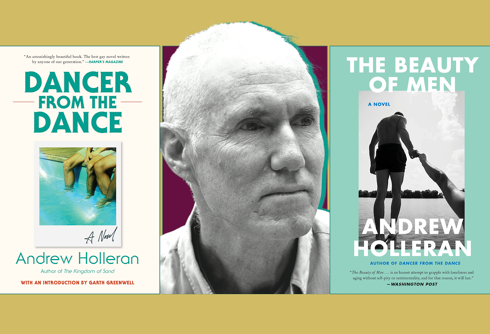

An award-winning journalist, Barnes has been covering the intersection of gender and sports for years. In Fair Play, they take on not only the question of how to integrate transgender athletes into sports at all levels of competition, but also the history of sex-segregated athletics and how sports both reflect and reinforce our cultural perceptions of gender. Exploring the science behind athletic ability alongside the real stories of trans and gender-diverse athletes, the book is a fascinating, empathetic read about a very complicated topic.

Related:

Here’s how the Biden administration plans to fight trans sports bans

While advocates are hopeful Biden’s proposals will help trans kids, many say it has taken too long for the administration to take action.

Recently, Barnes joined LGBTQ Nation to discuss some of the thorny issues they address in Fair Play.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

LGBTQ Nation: You write that “sports are coded, laden with allusions to gender and sexuality” and that they “reinforce what we believe to be true about gender.” Can you give us a sense of how?

Katie Barnes: Overall, culturally, we think of sports as a masculine activity. But then even within that, specific sports have certain cultural connotations. So, figure skating is seen as a feminine sport, football is for boys and men. Basketball is a more masculine sport, gymnastics is a feminine sport.

Of course, there are men who compete in gymnastics, there are men who compete in figure skating, there are women who play football. Boys and girls also play basketball. So, it’s not that these sports are only for those genders, but culturally, in terms of how we think about those sports, that comes with gendered assumptions. And I think that in terms of how that fits in with how we think about gender, it comes with the kind of performance we’re looking for. Is that performance anchored in strength? That is a masculine trait. Is it anchored in flair and balance, like figure skating? That is feminine. Those cultural allusions are pretty clear.

LGBTQ Nation: So what does that mean for the athletes competing in those sports and for the people who watch them?

KB: In some ways, the fact that these things exist is relatively neutral. It just is what it is. It doesn’t have to be deeper than that other than we can call it out and say that this is what’s happening. Alongside that, the impact of such coded gender allusions is that it creates, in some cases, a culture of repression when it comes to gender expression, and also sexual orientation. Looking at the ways in which people who compete in men’s artistic gymnastics, where gymnastics as a whole is seen as a feminine sport. It was interesting talking to people who have competed in men’s gymnastics or have competed in women’s gymnastics and have since transitioned—the culture in men’s gymnastics being one that is hyper masculine because you’re pushing against the stereotype. So then what does it mean if you’re a feminine gay man? Or if you’re like Jackson Harrison and you’re feminine and nonbinary in a sport that prioritizes and preferences a masculine expression of gender?

Similarly, we think about how queer women have felt historically in a variety of women’s sports where, because the assumption is that you’re participating in a masculine activity and are therefore less desirable in a heteronormative society—to be queer in that space is to confirm a stereotype. And historically, many queer women have chosen not to do that for a variety of reasons, one of which was the success of their professional league. It’s complicated, but overall, of course it affects athletes and it shapes their culture. But those cultures and the factors are unique to each specific sport and the genders that are participating in that sport.

LGBTQ Nation: Do you think that segregating sports by sex is still a useful model, or do we need a different approach?

KB: Yes, I still think it is a useful model—most of the time. One of the reasons that I think that is pragmatism, in that, regardless of my personal feelings about gender, the global sporting order is sex-segregated. So, undoing that, I believe, is a fool’s errand. From the standpoint of what actually is worth spending time discussing, reorganizing sports—I don’t know if that will happen.

Also, I have yet to be presented with an alternative organization that allows women, specifically, to hold world records and win gold medals and stand on podiums that are ostensibly equal to their male counterparts. Something that came up in that chapter from the National Organization for Women when they were dealing with how Title IX would be enforced was this worry that if we created an integrated sporting model women would not be able to make those teams because they didn’t have the training necessary, because until that moment they had been kept out of sports. So, at this point in time, given where we are, even as a variety of women’s sports are having a moment, there has still been market suppression all through women’s sports. And, given how sexism is still functioning and alive and well, I’m not confident that if those guardrails are removed in terms of separate sex segregated categories, that women who are good enough to compete against similarly sized men—that they would be able to do so, because of the ways sexism functions. That systemically would push girls and women out of sports, and would push all those who are marginalized by gender out of sports.

LGBTQ Nation: Lance Armstrong has suggested that trans athletes should compete against other transgender athletes in separate divisions and categories from cisgender men and women. I’m sure other people have suggested that as well. What do you make of that?

KB: I understand the impetus. The reality is, there are so few. So, who are they competing against? This desire specifically to put transgender women in their own category… I want to be very clear here: I think in general there are folks that want to have this discussion, or think that they’re talking about elite sports and they don’t necessarily say that out loud. So they just say, “Transgender athletes should have their own category.” And in the United States, the overwhelming majority of legislation that has passed into law is sweeping in terms of the breadth of ages that it covers. And it’s become clear that there aren’t that many transgender athletes competing at a high school level or younger. So, if we’re creating a separate category for competition for single high school athletes, are we going to have a national championship by default that is just decided by a race of four people? Two people? From a functional standpoint, it doesn’t really make very much sense to me.

Separate from that, I think it depends on what age group you’re talking about when we think about appropriate policy. For school-aged folks, the whole point of sports at that age is—yes, you learn competition, you learn what it means to win. You also learn what it means to lose. You learn how to be part of a team. You learn discipline. There are so many reasons why young people play sports, and the overwhelming majority of them stop at the end of high school. And so, when we look at how legislation is affecting transgender athletes’ ability to participate in a school activity alongside their friends—which ultimately is what we’re talking about at that age—the fact that it’s being so heavily restricted begs the question of why. And is that scientifically and physiologically appropriate?

LGBTQ Nation: So much of the debate around whether trans athletes, and particularly trans women, should be able to participate in sports seems to revolve around the concept of “fairness,” that trans women in particular have an unfair biological advantage over cisgender women. Now, that may be a kind of smokescreen for transphobia, but what do we know about the science behind this?

KB: We know that testosterone is athletically helpful. But everybody does have testosterone; I want to be very clear about that. So, when we talk about transgender athletes there is very little research on actual transgender athletes and the effects of testosterone suppression on athletic performance. What I mean by that is, yes, we know that testosterone is athletically helpful. We know that those who are assigned male at birth have more testosterone for longer, after testosterone-driven puberty, than those who are assigned female at birth. And we know that that leads to significant gaps in speed, strength, and power. We know all that. But cisgender men are not the same physiologically as transgender women. And we also know that. If you look at the data, testosterone levels are not the same. Muscle mass is not the same. Grip strength is not the same. VO2 max is not the same. That does not mean, however, that all of the physiological and metabolic indicators are fully suppressed in a way that matches a typical range for cisgender women as transgender women undergo testosterone suppression.

What is not known is how quantifiable that is on athletic performance. Because what we also know is that you can have great grip strength, but what does that have to do with soccer? You can have a better VO2 max indicator—your body’s ability to carry oxygen in your blood—and that does matter for endurance sports. But you also have to train. Sports are skills as well, and that is something that is really missing from this conversation. Just because somebody is taller than average doesn’t make them a good basketball player. And this is particularly true when we’re talking about lower-stakes sporting experiences. So, all of the things that I talked about, that’s the kind of conversation we have around our elite athletes. It’s how we talk about Michael Phelps. That is the level of scrutiny that we apply to our elite athletes because they are incredible athletes which means their bodies are doing something physiologically different than the rest of us.

However, for the rest of us, we don’t know our testosterone levels. We don’t know our femur length, our VO2 max. In general, if you are an everyday person who played high school sports or played travel soccer until you were 14—when you think about your everyday sporting experience, it is not subject to that level of scrutiny. From a scientific perspective, it’s one of the reasons why we don’t know a lot. But we do know that pre-puberty, the differences between those who were assigned male at birth and those who were assigned female at birth are very little. There are some differences, but it’s not overwhelming and doesn’t create an inability for meaningful competition between and within sexes.

In general, I think having more mixed sports longer is better for everyone. Whether you are a boy, girl, nonbinary, gender-fluid, trans, cis, intersex. If you are a kid playing sports, there’s no need at 7-years-old to have boys’ soccer and girls’ soccer. You can just have soccer. There’s very little reason to sex-separate our sports as early as we sometimes do.

LGBTQ Nation: I’ve also heard the argument that “fairness” in sports is kind of a false concept, because everyone’s body is different, everyone has certain physiological advantages and disadvantages—and I think you also make the point that access to and the ability to afford training and private instruction is also an advantage not shared by everyone. So, how are we supposed to think about “fairness” and “meaningful competition?”

KB: Meaningful competition is a concept that I got from Joanna Harper, who is a researcher in this space. She’s a transgender woman, herself and is working on a number of studies on transgender athletes currently. For me, meaningful competition, what I think is interesting about that idea is, to your point, people want a level playing field. Well, the playing field is never level. It just isn’t. Someone is faster, someone is a favorite, someone is an underdog. Somebody’s had a quarterback coach since they were 12, somebody has not. Certain schools have better facilities because they are wealthier than other schools.

So, fairness I feel like is a little bit of a red herring. But I do think what people generally want to believe is that when people line up in the starting blocks, when they step up onto the diving board, when they tip off a basketball, that the result is not predetermined, that it’s not immediately clear who is going to win because of something other than their training. I think in general there is this fear that the integrity of our sports will be lost because somebody who is a transgender girl or transgender woman is competing in a race and therefore it is predetermined that she will win. And we already know that that’s actually not the case. Even with an athlete like Lia Thomas who did win a national championship. She placed fifth, and she placed in eighth in two additional races that same weekend. She wasn’t unbeatable.

So, that meaningful competition piece is really important. But I will say, I think there are folks who really are proponents of restrictive policy for whom any participation by a transgender woman in women’s sports is a failure of policy. It’s not about whether she won. It’s that she was allowed to participate at all, and all policy should be restricting access to women’s sports for those who were assigned female at birth specifically. And it’s a real challenge if that’s where the conversation is.

LGBTQ Nation: And that’s just transphobia?

KB: I don’t necessarily like to label people’s feelings, per se. I think at all levels there should be a pathway to participation. And so, for me, that perspective is inappropriate and unscientific. I don’t think the science supports that at any level, but especially when we’re talking about young people. Similarly, I don’t think it supports it when we’re talking about intramural competition or recreational competition. If we’re restricting the ability to do that, I wonder are we going to start looking at birth certificates to see who can play pick-up at the Y? The stakes really matter and I think that also has been lost. So, if we want to have a discussion about appropriate policy, starting from a place of blanket restrictions in all cases at all times doesn’t make very much sense to me,and doesn’t hold weight scientifically at all.

LGBTQ Nation: Your book really lays out how complicated this whole debate is. And yet, it’s part of the conversation now. People bring it up. I had a barber ask me about it while I was getting a haircut, and even as someone who covers this stuff, I struggled to talk about it. How do you think people who care about trans and nonbinary people’s rights should approach those conversations?

KB: For me, what is most important in these conversations is empathy, is compassion and understanding, and underscoring that that goes both ways. What I mean by that is that it can be very frustrating to me when I lead with compassion and empathy and I am met with closed responses and a lack of openness. I think what is really important, and if anyone takes anything away from this book, it is that trans people are people.

As we are sitting and debating hormone levels and bone density and all of these things and applying such scrutiny to the bodies of this specific population, [know] that as we are doing that we are continuing to strip away the humanity of the experiences of these athletes. And there are real consequences to passing these laws, to changing these policies.

I think one of the most gut-wrenching moments in the book is learning how Lia Thomas learned her swimming career was over. Regardless of your perspective on this issue, she’s a person. Andraya Yearwood is a person. Mack Beggs is a person. And that truth has been lost in this discussion. So, I think in terms of how to have these conversations, it is to bring it back to the humanity of trans people, and also not diminish the concerns and the experiences of folks who have good-faith questions, who have differing perspectives. For people who are participating in sports and who care about their sports, it matters a lot, and I don’t think we should be dismissive of those perspectives either. But we also have to lead with compassion and empathy and openness, and right now there are a lot of closed perspectives and I think that’s causing a lot of people to talk past each other and it’s having a really negative outcome on all of us, including queer and trans people of course.

Don't forget to share: