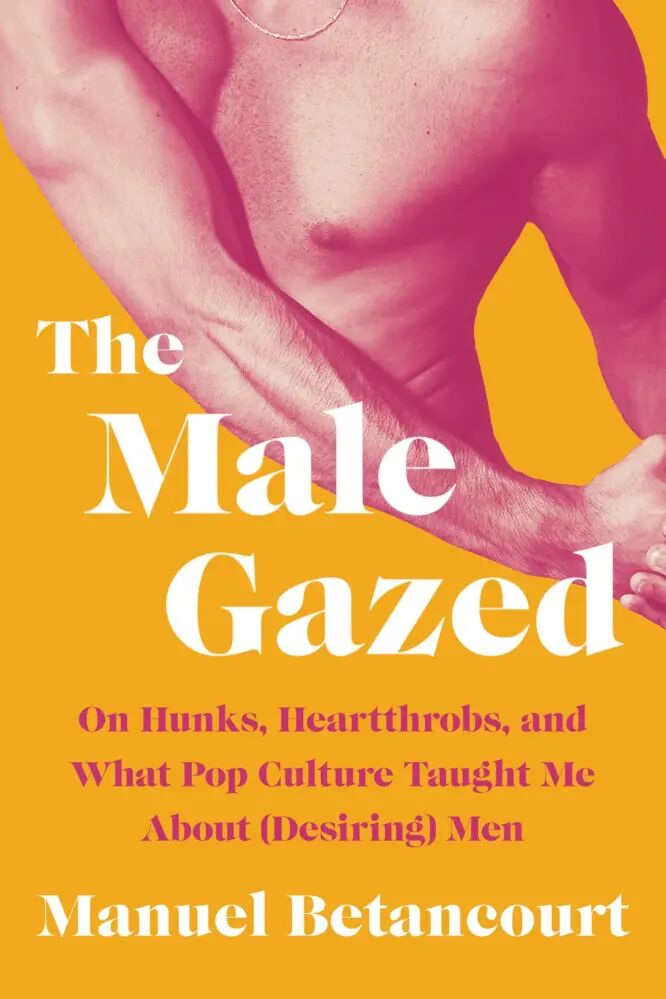

The Male Gazed: On Hunks, Heartthrobs, and What Pop Culture Taught Me About (Desiring) Men is a provocative new memoir and cultural critique by author Manuel Betancourt.

Betancourt dives deep into what defines masculinity, homoeroticism, and the exploitation of both in a gusher of pop-culture messaging that’s had the author, for one, drenched since a young age.

Related:

Gay writer Paul Rudnick won’t let the book banners bring him down

The author of “Farrell Covington and the Limits of Style” explains what’s motivating those 100 Million Moms.

Disney’s Prince Charming, The Little Mermaid, Mario Lopez in Saved by the Bell, Tennessee Williams, social media thirst traps, Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckenridge, Tom of Finland, Bob Mizer, Antonio Banderas, Calvin Klein briefs, telenovelas, Ricky Martin and Rex Reed all figure into the Colombian writer’s analysis.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

It’s one part dissertation, one part Hercules and Gaston fandom.

How the author reconciled the onslaught of imagery with his own experience growing up gay in Colombia is at the heart of his story, that of a fey, slight and bookish boy finding his place in a world where, as he puts it, “I live in my head, and I live in a world of ideas and writing.”

Two strategies: Baking and working out.

And more writing.

LGBTQ Nation spoke with Betancourt from Los Angeles.

LGBTQ Nation: What gym do you belong to?

Manuel Betancourt: I’m an at-home person. When I was in New York, I went to my local Planet Fitness because I was a grad student, and didn’t have the money to go to a fancy Equinox or the New York Sports Club nearby. And when I moved to LA, it coincided with the pandemic, and so I got very much into doing home workouts. So I’ve used the Peloton and often do their workouts here.

LGBTQ Nation: When do you work out?

MB: It’s always the time of day when I just am not thinking about myself, or the work of the writing, but I’m just focusing on sort of a half hour on the stationary bike or I’m doing yoga or I’m doing a little bit weightlifting. So most of it is as a way to be in my body sometimes, and then, because I’m vain and narcissistic, also because I like to look good, and I like to feel good. And, you know, as I struggle with in the book, I sometimes have a hard time phrasing it that way — that I want to look good — because I think it’s a very weighted kind of way thinking about male bodies and especially gay male bodies.

LGBTQ Nation: What’s your type?

MB: I like to think of myself as an equal opportunist. It varies on mood, because I tend to connect with people in terms of vibe. So when it comes to physical attributes, I have been known to go for very hunky, muscley guys, but also very lean guys, slightly thick boys, or tall, small and twinkish. I try to not limit the guys I seek or who seek me.

LGBTQ Nation: Are you in a relationship now?

MB: I am. I am in a throuple. So I have two boyfriends. And we’re all dating one another. So it’s like kind of close to triangle.

LGBTQ Nation: You grew up in Colombia watching Disney movies and American television, where you find a lot of gay subtext. When did you first come across the art of Tom of Finland and Bob Mizer, which are both homoerotic by design?

MB: In undergrad, I went through a phase of wanting to study more on queer arts, and so stumbling onto Basquiat and Haring I think I came across Tom of Finland. It’s funny because now I can’t think of a time when I didn’t think about Tom of Finland or know about him.

With Bob Mizer, it was in grad school. I was writing about cruising in San Francisco, and I think that led me down this rabbit hole where I found Physique Pictorial and Bob Mizer and his photography, and then, of course, I was obsessed.

LGBTQ Nation: What was your visceral reaction when you first encountered those two?

MB: Visceral is a great word, because I had a very bodily reaction. I think it was one of the few moments where I first encountered a queer, sexualized gaze on the male body that was intentional. Every other time that I found it, it was either unintentional or it was hidden or it was covert.

But in those drawings, and in those photographs, there’s no denying that the person who had the camera or the person holding the pen was very turned on and wanted us to be turned on by what we’re watching, and what we’re observing. And that was mind-blowing to me. And I think it’s still mind-blowing to me. I still love looking at those Mizer photographs, and those Tom of Finland sketches and drawings and illustrations. No matter how many times I’ve seen them, they still create a visceral, bodily reaction that I really enjoy.

LGBTQ Nation: Let’s talk a little bit about Instagram. I get a sense from the book you have a problem with it.

MB: I have so many friends who are artists and who do a lot of work that is figurative and erotic and that plays with nudity. And I’ve been seeing firsthand how a lot of their posts get taken down, even though they fall under the kind of rules that Instagram has laid out, which is: when it comes to art, so long as it’s art, it should stay up. And a lot of it gets taken down.

I’ve seen friends getting their accounts suspended, and then needing to build themselves back up. And it really comes down to this prudish idea that nudity is equal to sexuality, that this is not something that should be on the web for everyone to see. It really entrenches ideas about how we think about bodies, which I don’t particularly enjoy.

It’s funny, when you said that I have a problem with Instagram, I was like, I use it a lot, so it’s a very weird, vexed relationship that I have. Seeing in the past five years that it’s turning into a not particularly welcoming home for queer artists, and queer art that is a little bit more erotic, it’s kind of sad.

LGBTQ Nation: Do you see a double standard with straight art?

MC: Oh, absolutely. How my friends share it is: This picture of a scantily clad woman is allowed to be up, but if you post a semi-naked guy in briefs, then apparently you’re violating their guidelines. And it’s funny because I’ve had one or two moments where I’ve posted an image and it’s been taken down just because I’ve been in a Speedo, or I’ll be like, slightly suggestive, but nothing really insane. The annoying part is you have no recourse to really fight those things, unless you know someone on the inside or you make it an entire bureaucratic nightmare for them.

LGBTQ Nation: Is that a fear of how Tumblr became so explicit?

MB: I think so. You start noticing that all these public social spaces online thrive on queer artists that create an audience, and then they kind of lose them. So I think there is that fear. These artists will keep hopping and hopping but, you know, where do we go next?

LGBTQ Nation: How do you think dating apps like Grindr and Scruff affect men’s self-esteem?

MB: They have created a wave of anxiety that we all have about what we’re supposed to look like to be desirable, especially among people who are not, you know, white and fit, and don’t fit a particular kind of model. I think that’s always been there within the community, but they’ve exacerbated the issue, and it’s become harder to ignore. Because now we have receipts, and we have ways of actually seeing them play out right in front of us in ways that maybe before were a little more discreet.

LGBTQ Nation: What do you think that model is?

MB: I mean, it’s on the cover of my book. This idea there’s 0% body fat, beautiful pecs, beautiful abs. You know, they’re white, they’re lean, they’re fit. I think there’s a way in which still we valorize this kind of body, and anyone who deviates from that has a hard time.

I shouldn’t say ‘has a hard time,’ but I would say that it can sometimes feel like you’re internalizing that you should be looking like that one person, or this one beautiful hunk or heartthrob.

LGBTQ Nation: Is it a contradiction that those apps may present the “model” version like you’re describing, but at the same time, they are a very wide and deep pool of all kinds of types, and offer all kinds of different experiences to choose from?

MB: As with everything else, as long as you think of it as a tool, a tool will never inherently be good or bad. It will always be about how it’s used. There are ways in which those apps have probably opened up a lot of experiences. And it isn’t that it is so much easier to find like-minded people who like what you like, or who want what you are offering. Before, you went to specific bars or specific alleys or specific parties for that. You could think of it as a democratization of a kind of cruising.

LGBTQ Nation: You ask early in the book, Do I want him? Or do I want to be him? What’s the answer for you?

MB: It’s both for me. That became the animating question of the entire project. There are moments when I couldn’t discern the answer, where sometimes, when I am attracted to someone, there is a level of, what I’m wanting in them is what I want for myself — this doesn’t only have to be physical, it can also be in terms of the kindness or tenderness that they’re offering — and recognizing that that is a valid way of thinking about desire. But most of the time I find myself falling into the “it’s both” category. It was a very helpful kind of intellectual exercise that I now find myself asking all the time.

LGBTQ Nation: Do you think that experience is unique to homosexuality, or does it cross over into straight relationships as well?

MB: It seems like a very queer question, just because of the same-sex desire. It’s easier to see how I could want to be the really hot guy at the gym or want to be that really smart guy at the library. And that it’s not just what I want from them, but what I want in myself.

But as someone who grew up watching a lot of Hollywood rom-coms about straight people and still finding things in those relationships or in those characters about myself, there’s a way of breaking through that gender barrier and actually learning something about yourself. So even though I think of it as a really queer question, I have no doubt that straight or non-queer people could also, and do, experience questioning themselves.