In June 2015, the same month as the Supreme Court’s historic ruling recognizing same-sex marriage, Adam Motz and Tee Lam had their second date, at the upscale Cherry Circle Room in Chicago.

Over a romantic dinner, Lam, a property manager, brought up the subject of kids — not the usual topic of conversation this early in the game. But Adam, an attorney, had also been dreaming of having a family, and the question sealed the deal for their relationship.

After dating for several years, the two were married in March 2019.

“Tee had been wanting kids for a really long time and had been trying to make it happen, so he just broached that with me,” said Adam, 33. “So we got it out of the way right up front as we both knew it was something we wanted, and we were gonna try to do it quickly after we got married.”

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Adam and Tee, 39, finally realized their dream on August 6, when a surrogate gave birth to their twin girls in Los Angeles.

Their story of meet-cute, marriage and making a family is just one example of the striking progress and growing acceptance of LGBTQ parents in America.

In the mid-1970s, Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign accused gays of recruiting, abusing and warping America’s youth. The campaign, and dozens lesser known ones, created a hostile atmosphere for any LGBTQ person who had children or wanted to be a parent that lasted decades.

Fast forward to 1989, when the children’s book Heather Has Two Mommies sparked national outrage, book burnings, and a debate about whether same-sex couples should raise children.

Some gay parents lost custody of their children: Sharon Bottoms was a 23-year-old-lesbian in 1993, when her 2-year-old-son, Tyler, was taken from her and given to her mother to raise. The case made national headlines when the Virginia Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling that said Bottoms’s same-sex relationship “was illegal and immoral” and “renders her an unfit parent.”

As recently as 2012, Rick Santorum, then a Republican presidential candidate, said children are better off with a father in prison than being raised by two moms.

A year later, when the U.S. Supreme Court was debating whether to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act, Justice Antonin Scalia stated there was “considerable disagreement among sociologists as to what the consequences are of raising a child in a … single-sex family, whether that is harmful to the child or not.”

In reality, there had already been voluminous research showing kids in LGBTQ families fared just as well or better than their peers. The “body of research has shown that the adjustment, development and psychological well-being of children are unrelated to parental sexual orientation and that the children of lesbian and gay parents are as likely as those of heterosexual parents to flourish,” the American Psychological Association declared of a comprehensive survey of the research on the topic.

In 2015, when the Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of marriage equality, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion recognized the importance of providing a stable family environment for the children of same-sex couples.

“Without the recognition, stability, and predictability marriage offers, their children suffer the stigma of knowing their families are somehow lesser,” Kennedy wrote.

Since then, opinion polls show public acceptance of gay families has grown exponentially: Today, 70 percent of Americans support same-sex marriage, including majorities in nearly every demographic. And nearly 60 percent of Americans say they wouldn’t be upset if their child came out.

How It Started, How It’s Going

Today, the cultural, social and legal conflicts over same-sex parenting have changed. LGBTQ families are commonplace and appear regularly on TV shows such as The Fosters, Glee and Modern Family. In August former Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, now U.S. Secretary of Transportation, announced he and husband Chasten had become parents.

According to the advocacy group Family Equality, nearly a third of all LGBTQ adults are raising kids, and more than two million children have at least one queer parent.

A U.S. Census report from 2020 indicated almost 15 percent (14.7) of the 1.1 million same-sex couples in the United States had at least one child under 18 in their household, compared with 37.8 percent of heterosexual couples.

Years of research indicates those children are doing just great: Abbie Goldberg, a Clark University psychologist who has studied parenting for more than 15 years, told LiveScience in 2012 that LGBTQ parents “tend to be more motivated, more committed than heterosexual parents on average, because they chose to be parents.”

A 2018 study in the Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics showed that children of gay parents were just as well-adjusted psychologically as those raised in straight homes.

And a European study the following year suggested children of same-sex couples performed better in school and were more likely to graduate.

“Our findings suggested that children with same-sex parents fare well, both in terms of psychological adjustment and prosocial behavior,” said Roberto Baiocco, a professor of developmental psychology at Sapienza University of Rome who authored the study.

A comprehensive Cornell University meta-study determined 75 of 79 reports on same-sex parenting over the past quarter-century indicated no difference in outcomes for children raised by LGBTQ parents versus those with straight parents.

“It is liberating for parents to take on roles that suit their skills rather than defaulting to gender stereotypes”

Child-health expert Simon Crouch

“Children’s well-being is affected much more by their relationships with their parents, their parents’ sense of competence and security, and the presence of social and economic support for the family than by the gender or the sexual orientation of their parents,” according to Boston University pediatrics professor Benjamin Siegel.

In fact, there’s evidence that the structure of queer families is beneficial to children: “Same-sex parents, for instance, are more likely to share child care and work responsibilities more equitably than heterosexual-parent families,” child-health expert Simon Crouch wrote on The Conversation in 2014.

“It is liberating for parents to take on roles that suit their skills rather than defaulting to gender stereotypes, where mom is the primary caregiver and dad the primary breadwinner. Our research suggests that abandoning such gender stereotypes might be beneficial to child health.”

Family Equality was founded in 1979 to support gay parents and advocate for legal changes to protect their rights. At that time, the children of most LGBTQ people came from previous opposite-sex relationships.

Today, 63 percent of LGBTQ millennials — those born between 1981 and 1996 — want to start a family of their own, through fostering, adoption, or assisted reproductive technology (ART) such as surrogacy and in vitro fertilization.

This generation is also more likely to identify as LGBTQ: A 2020 Gallup poll found that 9.1 percent of millennials identified as something other than straight, compared with 5.6 percent of the general population.

But legal, financial and cultural obstacles for queer people wishing to start a family still exist, and the route to parenthood can be slow, complicated, and expensive.

The Insurance Labyrinth

For couples and individuals looking to have children through ART, the biggest barrier isn’t biology, it is health insurance.

Acquiring eggs or sperm can cost close to $5,000, with in vitro fertilization running $20,000 per attempt, and surrogacy costing $80,000 or more.

Many insurance companies won’t cover ART costs for same-sex couples, as Adam and Tee found out when, even after assurances, their insurer denied their claims for egg donation and fertilization.

Most insurers require a couple to try for a year to conceive through sexual intercourse before they will cover ART. Someone with a uterus without access to sperm would have to attempt intrauterine insemination 12 times before their plan will cover egg donation.

Adam and Tee’s carrier doesn’t consider their lack of a viable egg a medical issue, so they had to pay nearly $20,000 out of pocket for prescriptions and services.

The couple had actually tried to eliminate some of the roadblocks to parenthood by having Adam’s best friend from high school donate her eggs and a longtime friend of Tee’s be the surrogate.

“We knew there would be challenges and things we didn’t expect along the way,” said Adam, who says the claims issue remains unresolved. “But we never imagined that the biggest obstacle in all of this would be that our own health insurance company would refuse to pay for services that they would otherwise cover for straight couples.”

The problem isn’t just about money, he added, there’s an emotional toll, as well.

“We’re working so hard to start our family, and we have a corporation refusing to pay for reasons that they plainly stated were discriminatory,” he said. “We were told so many things by so many different people that it really makes us question what’s their actual motivation there.”

New York, California and Maryland have laws requiring companies that offer pregnancy benefits to also cover fertility treatments for people like Adam and Tee, but there is no federal mandate.

A few weeks before the twins’ birth, Adam checked in with their insurer to see if they needed to do anything to add the twins to their insurance policy. But the customer service representative didn’t understand his fairly basic inquiry.

“These companies do all this rainbow-washing during Pride, and they claim to support the gay community,” Adam said. “But when it comes down to it, not only do they refuse to pay for basic services like these, but they’re also just not versed in these things.”

Family Equality has an online program, Open Door, to train family-building professionals, lawyers, social workers and others involved in the process. The modules cover the nuts and bolts of queer parenting, as well as respect for differences in family structures.

Jess Venable-Novak, Family Equality’s director of family formation, said some insurers have signed up with Open Door, but acknowledges there’s still more work to do.

“Having access to insurance is still such a privilege for LGBTQ people,” they said. “But even if you have that access, it’s not helping you in many areas, especially family building and fertility issues. So we have a long way to go for that.”

Getting Creative With Conception

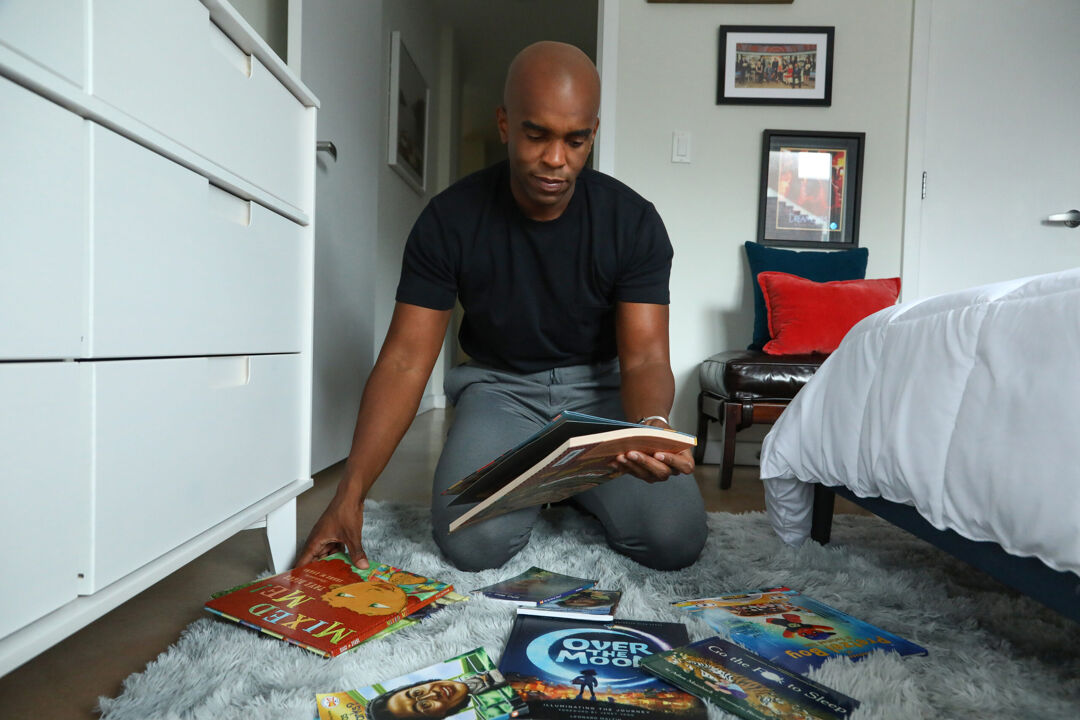

Given the legal and insurance challenges, some members of the community have chosen to forge their own paths to parenthood. Chris Witherspoon, a 39-year-old reporter in New York City, is one of them.

Born to a strict Baptist family in Ohio, his interest in being a gay dad was set in motion by the groundbreaking 1990s sitcom Will & Grace.

“In 1999, I was not out. I was living at home and ‘Must See TV’ was a big thing for me,” Chris said. He’d watch the Emmy-winning comedy about a gay man and his female best friend alone in his room with the volume turned down.

“I’ll never forget, when I was a senior in high school, I said to myself, ‘I’m gonna move to New York and get a roommate who’s gonna be a woman – i.e. Grace – and we’re gonna to have a kid together.’”

Sure enough, in 2005, he put that plan into motion — moving to Manhattan and becoming fast friends with a lesbian who worked at a posh hotel. Within a year they were best friends, and then roommates talking about co-parenting a child.

In July 2010, they began the road toward conception — without doctors, insurance companies, or lawyers. And in 2011, Chris’ friend, who asked not to be identified for this article, gave birth to their son, Andrés.

Chris has kept the details of Andrés’ conception private, saying only, “I am fully gay and she is fully lesbian.”

While it required an immense amount of trust, their path meant both had parental rights to Andrés the moment he was born.

“We’re both on the birth certificate,” Chris said. “We didn’t have to see a lawyer and draw up documents around any of this. It’s just two people who had a kid together, and we have equal rights: I’m his father and she’s his mother.”

An older, gay friend who’d been a parent and went through a messy divorce advised Chris to consult a lawyer.

“My whole life has been coloring outside the lines and trusting my friends, especially in this community,” Chris said. “This is one of my dearest friends. And I’m gonna go on the faith that she wants this as bad as I want this. And that she knows that we’re each other’s only option in this.”

Plus, he added, “I can’t afford to pay lawyers thousands of dollars.”

Chris and Andrés’ mom remained roommates for a year after the birth and then decided it would be best that they each have their own space.

Witherspoon remains single, but he is in love with being a father. And Andrés, who just turned 10, is especially proud of his dad, whom he likes to out to his classmates and friends all the time.

“He tells his friends sometimes before I can tell them,” Witherspoon said. “Almost like it’s a point of pride. He just loves people knowing I’m different and that we march to the beat of our own drum.”

People’s attitudes about his family dynamic have changed tremendously since Andrés’ birth, Witherspoon said. Today, it is gay people who are saving our children, quite literally.

When he began this journey in 2010, it was a year after Modern Family debuted, and he said people used the show — with a gay couple adopting a baby as central characters — as a comfortable frame of reference. The general acceptance of gay parents has grown extraordinarily, Witherspoon said, calling it something of a relief.

“It’s not as scary as it was 10 years ago to dare to be gay and be a parent,” he said. “You have celebrities every week coming out and having kids.”

“All in” on starting a family

Neil Patrick Harris and David Burtka are a celebrity couple who have been very public about being dads. Their twins, Harper and Gideon, were born in 2010. But for David, now 46, it wasn’t his first time raising twins: In 1999, he was a 24-year-old working actor when he went on a date with actor-director Lane Janger.

“Lane said, ‘I have to tell you this just to get it off the table – I’m having kids.’ He had met the surrogate that same day,” David recalled. The two fell in love and David was, as he put it, “all in” about starting a family.

He always knew he wanted kids — he was raised in a large Midwestern clan with lots of wonderful family get-togethers. He just never thought he would be so young when it happened. Eventually, the couple welcomed twins Javin and Flynn.

A straight 24-year-old man with kids might not sound unusual, but in the late 1990s, for a gay twentysomething to be a parent was practically unheard of.

“I met a couple guys in Seattle at a gay bar when I was doing a US Army ad campaign out there,” David recalled. “And they didn’t believe I had children. They thought I was lying.”

While his romantic relationship with Janger didn’t last, he helped raise the twins for several more years. Afterward, he stayed involved in a role he describes as akin to an uncle.

In 2004 he met Harris, who originally didn’t see a family in his future. But when he got to know David and saw him around the twins, he started to like the idea of having children of his own.

“He got to spend time with Javin and Flynn as I would hang out with them when I was in L.A.,” David said. “He thought he’d be a great dad, but didn’t think he’d ever find someone with the same interests. When he saw me interacting with the kids, that all changed. Neil called me the Pied Piper of Children. And then, after my mom died, we thought it was time to stop waiting, and just do it.”

What’s changed the most in his two experiences raising children, David said, is the sheer number of queer families. He doesn’t recall knowing any the first time around, or having a place to go for advice.

“Now we have a bunch of gay friends who have children,” he said. In fact, he and Harris have been a source of support for other friends becoming parents, like the Modern Family actor Jesse Tyler Ferguson and his husband, Justin Mikita, as well as head of YouTube fashion and beauty partnerships Derek Blasberg and Nick Brown, who recently became fathers to twins.

“We’ve coached a lot of gay couples who want to have children,” David said. “It’s been kind of nice to help lay the groundwork like that.”

It’s a daunting process, after all, one that can take years and tens of thousands of dollars.

“You really have to be brave enough to jump into it. It’s not just something that happens,” David said. “I think every straight person should go through all the process and pay all that money to have kids. Because there’s a lot of parents out there having kids who should not be having kids.”

From Fostering to Family in the South

Chelsey and Bailey Glassco’s path to parenthood began in Alabama. According to Family Equality, the highest proportions of same-sex couples raising children are in the South and Midwest, in rural areas that have the fewest protections and resources.

The two met in 2010 at a private, all-women’s Baptist college where homosexual conduct was forbidden. They felt like they were walking the halls with scarlet letters, but they kept their heads down, graduated, and, in 2011, got married.

They found work in Talladega, and after they got a house in nearby Childersburg, began thinking about starting a family—specifically, fostering a child in need.

Legal costs for fostering average less than $2,000, and financial support is often available from the state, but it’s a long and bumpy road for LGBTQ couples, especially in a conservative state like Alabama.

The Glasscos said several agencies refused to train them as foster parents because it went against their religious beliefs. They finally found an agency that would accept them, and spent six months on therapeutic training.

Shortly thereafter, they took in a girl, who lived with them for a year, until she turned 18.

Then came Brayden, age 5.

Brayden had faced abuse and neglect with his biological family and had been labeled disruptive at two previous foster homes. But the Glasscos thought, with their training, they could be a good match.

“It all started almost as an impulsive decision,” said Chelsey, 31. “We thought, ‘This boy needs help, we have an extra bedroom, we can do this.’ But we tried to have no expectations because we knew that so many times the child goes back to their birth family.”

Brayden arrived in 2016 and, and at first, he was a little confused that his new foster parents were two women. After a few days, Chelsey said, “he got it.”

“Kids are like, ‘OK, two chicks. Moving on.’ You know, it doesn’t really worry them,” she said. Brayden’s biological father at first had some issues with their sexual orientation. But they didn’t take it personally.

After a few months, Brayden began asking them if he could stay permanently. So the Glasscos decided to take the big, uncertain leap to adoption.

Less than half of U.S. states have nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people in public accommodation. Even In Philadelphia, where city contractors must abide by LGBTQ anti-discrimination policies, a narrow Supreme Court ruling in June allowed an adoption agency to continue rejecting prospective parents based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

In 2017, Gov. Kay Ivey of Alabama signed legislation making it legal for private, faith-based adoption agencies to turn away same-sex couples. The team of social workers that represented Brayden supported the Glasscos’ efforts, though, and after a tense one-hour wait, a probate judge granted them full adoption rights.

Since then, Chelsey and Bailey have found that even in their conservative part of the country, people are curious about, but mostly accepting of their family.

Bailey put it more frankly.

“No one gives a shit,” she said. “The judges and the politicians care. But most people day to day don’t care. Really, nobody cares. And the people who do care probably need to keep their noses in their own business.”

What really matters are the changes they’ve seen in Brayden: Initially, he had emotional issues and was taking multiple medications. Now, he’s a polite, curious fifth-grader getting A’s and B’s and nurturing an obsession with Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr.

He even got to fulfill a long-held dream with a family trip to Disney World in August. His two moms believe the key to this turnaround is one simple thing: love.

“What we hear from him repeatedly is that, ‘I have two moms that give me all their love and all their attention. And I have so much more than so many,’” Chelsey said. “It’s nice to hear that he realizes he’s where he belongs, and that he’s very loved.”

Connecting with other same-sex parents is a little harder given their remote location, but the Glasscos use email chains and Facebook groups. And they embrace being a model for others who might want to start a family in the Deep South.

“We did a foster parenting panel in Montgomery recently,” said Chelsey. “We try to talk about our experience a lot because we like to encourage people. If there’s any way that our story can help someone else, then it’s worth it.”

Having grown up in anti-gay homes and struggled through the coming out process, the Glasscos, like other LGBTQ parents, said knowing that they might be as conventional as any straight family is sometimes hard to process.

“We own a home, and bought two vehicles, and we have this almost American dream kind of life,” Chelsey said. “And to have a child, someone who depends on us for everything and looks to us for all of his needs? It can be surreal at times. But just being with him is just natural — he belongs with us.”

Brian Sloan is a New York-based writer and filmmaker with bylines in The New York Times, NBC News, and Business Insider; and films on Netflix, MTV/Logo, and YouTube.