Dana Tai Soon Burgess has been a leading figure in the dance world for over 30 years. But it wasn’t until the pandemic that the out Korean-American choreographer had a chance to really reflect on his career.

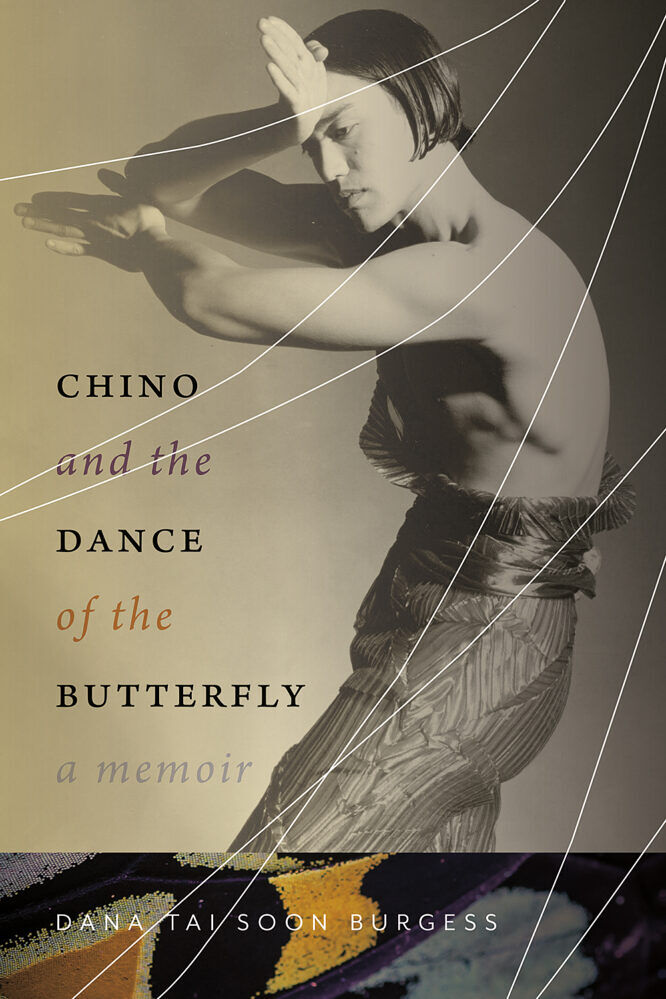

“With the performing arts especially, we’re always kind of in a mindset of the next presentation, the next thing, because we have to be in rehearsals for the next show,” Burgess told LGBTQ Nation. “But during COVID, all of a sudden, I’m not at the studio every day, I’m not seeing the whole dance company in person. I had this moment, like, ‘I need to understand how I got here, where am I going, what’s important to me in my life.’ I think everybody had that great quieting moment, right?”Burgess started to write, and the result was his recent memoir Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly. “It was my way of checking in with the last few decades of my life and figuring out, ‘How did that career get built and what was important to me?’”

Related:

Gay punkers & whackers: How an LA dance style was born

“Men were dancing together and kissing and hugging, and I actually freaked out,” says Viktor Manoel, one of punking’s creators.

That career has included some pretty momentous accomplishments. A dancer since he was a teenager growing up in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Burgess has served as a cultural ambassador for the U.S. State Department and, in 2016, was named the Smithsonian Institution’s first-ever choreographer-in-residence. His dance company — the Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company — is currently celebrating its 30th anniversary season.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

He’s also starting something of a new chapter.

This May marks the end of his tenure as the Smithsonian’s choreographer-in-residence with a performance of his company’s piece “Transformations” at the National Portrait Gallery. Burgess will expand his work with museums across the country, with new commissions from the Kreeger Museum of Art in D.C., the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Noguchi Museum in New York City. On a break from his busy schedule readying “Transformations,” LGBTQ Nation chatted with Burgess about dance, art, and identity.

LGBTQ NATION: Your work is centered on the experience of the “hyphenated person.” What does that mean to you, and how do you translate that concept into dance?

DANA TAI SOON BURGESS: I think this intersectionality, all the different pieces that make up my identity and other people’s identities, and create unique stories — those are the things I’m interested in. Part of my identity is Korean-American, part of it is dance, part of it is gay, and where they all intersect is the lens that I see the world through. When I started as a choreographer-in-residence at the Smithsonian seven years ago, I thought about that a lot, and I started looking at the collection and thinking: What are the stories that haven’t been put to the forefront of American history, which are diverse stories, and how can I illuminate those through dance? So that’s where I really started, and continue to work that way.

How does that intersectional perspective influence the pieces you create? How do you translate that into movement?

I’m very interested in research when I’m making a dance. I’m interested in individual stories. I’m interested in historical events which have shaped the American tapestry. So, I have to research what was going on during these time periods. What was the socio-political context? If I’m inspired by a piece of art, what was the painter’s life experience like? What was the sitter’s life like? What was going on within music and fashion during that time period? All of those things help me be inspired, and from there, I can use that as a jumping-off point.

You recently published your memoir, Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly. So, let’s talk a bit about your life. Your parents were both visual artists, but how did you become interested in dance specifically?

I never had this propensity towards being able to draw or paint. I just didn’t have it. So, as a child, I was always kind of waiting and looking for what my artistic medium was going to be. Finally, one day my father said, “Why don’t you take a dance class with your friend Salome?” Believe it or not, her name really was Salome, like the dancer in the Bible, which is hilarious in retrospect. So, I took this ballet class, and then I took a modern dance class, and in retrospect, they were hilarious classes. This modern dance teacher had, like, a tie-dyed tutu on, and he had these strange wool tights and a tambourine and was sort of doing an improv class. I thought, “Oh my god, this is modern dance?”

But out of those experiences, I immediately thought, “I can do this. This is going to be my calling.” The reason I think that happened is I had been a competitive martial artist from 8 years old until almost 15, and the discipline that you have in martial arts and the way you use your body is just so similar to modern dance and ballet that it just immediately clicked for me that what I had been missing from martial arts was the artistic, creative component. And I had found that synergy.

Growing up as a queer, Korean-American kid, were there role models in the world of dance who you felt represented you?

As an older teenager, dance was such a safe haven. There were gay male dance icons that you could look up to. I had this wonderful dance director at the first company I danced for, Tim Wengerd, who was a soloist with the Martha Graham Dance Company for years and years before he returned to Albuquerque, where I danced for him. He was such a great role model, such a fun person. So, there were these individuals that were not in other aspects of my life.

Did you feel represented in the world of dance?

No. I’m from the generation where you rarely — unless you’re talking about a dance company, say, in Hong Kong or Korea, Japan, etc. — see any Asian-Americans or Asians in a dance company. Especially male dancers who would have a leading role. There were very few in America. It’s hard for me to even count on one hand who they would have been back then.

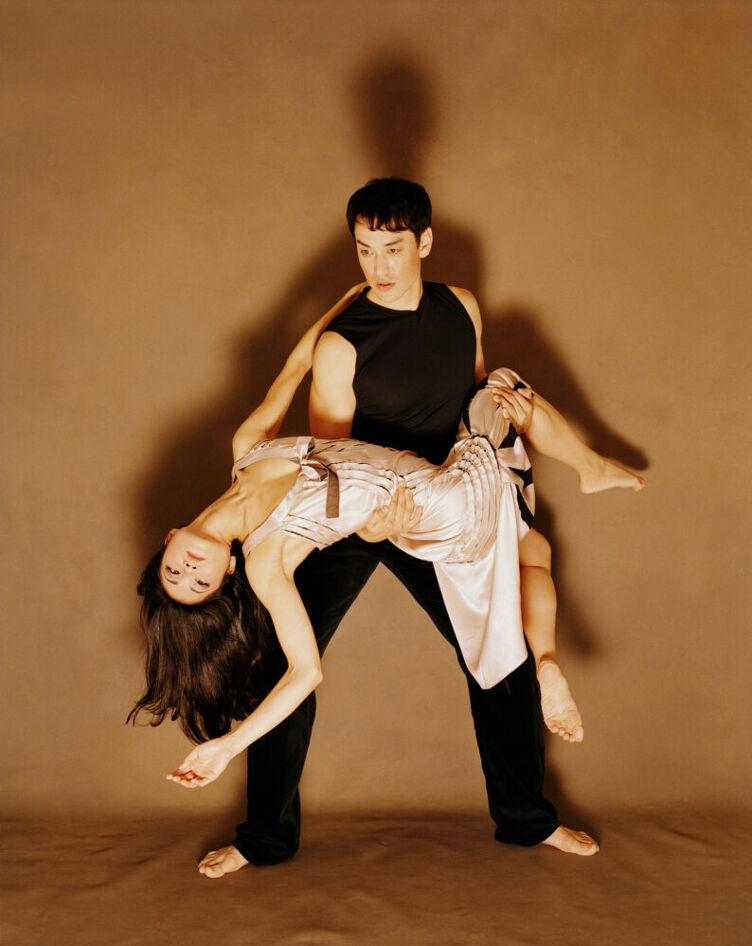

I love this idea that I read on your company’s website of “approaching the stage as a canvas, and the dancers as brush strokes.”

What I would love for the audience to take away when they see my dances is not only to reach this moment of empathy and have a sense that they’ve seen something sublime and beautiful but that if at any moment the stage froze, or they took a photo of the stage, that there would be this perfect tableau. I love the idea of moving tableaus, of thinking of the proscenium as this giant canvas, and as the dancers move, it’s these moving, reconfiguring, reconvening canvases that constantly happen in my work. I think that’s one of the signatures of my aesthetic.

Does that approach come from having grown up with visual artists as parents?

I definitely think so. All of the work I do with museums and with visual artists, art galleries, etc., has to do with my comfort level having grown up in a visual arts community.

What is the process of translating works of visual art into movement?

It’s not that I’m looking to copy into physicality, or in a kinesthetic way, an existing painting or an existing photograph. It’s more about looking at a collection, looking at specific pieces, and reconsidering what, through the history of that piece, is an entry point for creating the story around a new dance that will touch the audience. So, I’m looking at visual arts always as sort of a starting point.

Other commissions I’ve had are more specifically about an individual piece, and I’m happy to explore even closer a story format as well. But my dances range from abstract to narrative in nature. I’m looking for ways to create stories through dance that are inspired by visual arts and visual artists to tell stories that are uniquely about the human condition. And so many of the stories that I end up expressing through my dances are about the fundamental needs that we all have. I believe those needs are that we’re all in search of a place to call home, which is really a place to dream, to feel safe within dreaming, and we’re in search of a community that will embrace us. Those are the messages that I always work into the dances.

I believe that we’re all in search of a place to call home, which is really a place to dream, to feel safe within dreaming, and we’re in search of a community that will embrace us.

Dana Tai Soon Burgess

Do you remember the first time you looked a painting and were inspired to create a dance piece around it?

I do, but it’s so long ago… There’s this big abstract painting that my father did, and it used to hang over my parents’ bed. I remember when I was a child, I would lie underneath it and stare at it. Many times, I would envision little dancers moving around the painting, or I would be inside the painting moving. It’s one of my earliest memories. I think I’ve always been somehow in that place where a painting inspired movement.

You’ve said that your goal in your role at the National Portrait Gallery is to “mine the exhibits and the permanent collection for unique American stories that celebrate diversity” and the stories of marginalized communities. What has delving into the collection shown you about the museum’s and — by extension — the nation’s values?

In working with museum collections, what becomes apparent is how museums were first formed and what their perspectives were. You have to go back to the Edwardian age and the Victorian age, and you start seeing that there are these wealthy aristocratic families that are sort of building their own libraries of the exotic. They’ve got their stuffed birds and their items from Egypt that were sent back from a tour and their Asian antiquities. So, out of that mentality starts to grow these collections. As time transpires, the way that a society looks at the power of a museum and what a museum should reflect in terms of its collections changes.

But that’s to say that the majority of collections in museums are still really trying to catch up with the concepts of diversity — whether that’s LGBTQ+, African-American, Asian-American, Latino, or Native American. Still, the collections are not as representative as they could be. For me, I like to go into the collections, find out what the upcoming exhibits are, and really focus on those areas. I’ve found that that also enlightens me because in my journey to do research, I learn so much.

On your podcast, Slant, you explore questions of race, identity, and being a creative person in America with prominent Asian American writers, artists, and thinkers. What have those conversations taught you?

What I find with each conversation is how diverse the Asian American community is. Because we have the Vietnamese American experience, we have the adoptee experience, we have Korean Americans, Japanese Americans, Thai Americans, Cambodian Americans, etc.

There is just such a range of diversity that is umbrellaed under this huge term of “Asian American.” So, we really get to uncover these personal stories, these individual narratives that have shaped artists and writers and film producers that, without having personal conversations, we’re not going to get to. I also feel that honoring those individuals so we can hear their voice, hear how they describe their life experiences through their recorded voices is really important as well. I’ve been trying to focus on lots of different generations.

There are some individuals like David Henry Hwang [M. Butterfly playwright and three-time Pulitzer Prize finalist] who is older and speaks about his path and his career. But then there are some very young artists who are just starting out in their careers, and to hear their trials and tribulations, and also their different approaches and thoughts about issues like the resurgence of anti-Asian violence is really moving.

Do you have a dream guest that you haven’t spoken to yet?

Well, it’s probably the whole cast of Beef right now. I watched the whole thing twice!

This interview was edited for length and clarity.