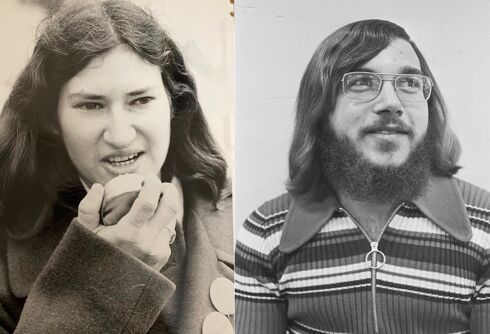

Since the release of the exceptionally successful yet execrable 2014 film The Imitation Game which grossed $234 million on a $14 million budget, this is the image of Alan Turing that most people who saw the film seem to remember.

Once a giant, a scientific genius who helped win WWII, now a pale, frail, flailing 41-year-old man, still shuffling about in his pajamas in the middle of the day and weeping hysterically because he’s been broken physically, emotionally, and psychologically by the drug a judge ordered him to take and by his government who stepped on him like an insect when they learned he was homosexual; begging visiting former colleague and brief fiancee Joan Clarke not to let “them” take the huge computer in his living room, the one he calls “Christopher” after his deceased boyhood love.

Related: Gay mathematician Alan Turing will be honored on the £50 note

“If I don’t continue my treatment they’ll take him away from me.”

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

There are a few problems with this scene: Clarke never visited him at his home; he never called any of the computers he worked with “Christopher”; the University of Manchester for which he was then working had nothing to do with his hormone “treatment”; it’s insane to imagine they would put their big computer in his home.

But the larger problem is that Turing was not broken; not by the police, not by the court, not by the British government. Those who believe he was are expressing subjective opinion not objective fact. And one must ask why some seem to want to believe he was.

Touted as “inspired” by the 1983 768-page biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges, the Oscar-winning screenwriter repeatedly tooted that, “Historical accuracy was tremendously important to us.” But his script grossly ignores much of what Hodges wrote and got so much incomprehensibly wrong, went so inexplicably beyond typical liberties, that a legion of articles appeared cataloging and correcting them; beginning with the fact it got the year wrong that he was arrested.

“The Imitation Game jumps around three time periods – Turing’s schooldays in 1928, his cryptographic work at Bletchley Park from 1939-45, and his arrest for gross indecency in Manchester in 1952. It isn’t accurate about any of them. Historically, The Imitation Game is as much of a garbled mess as a heap of unbroken code.” – The Guardian.

There are two fictions above all that are unforgivable; so much so that they amount to crimes against Turing’s humanity. The first:

The character threatening Turing in this scene, wrapped in the blond visage of one of Downton Abby’s favorite actors, was based on real life Soviet spy John Cairncross. But contrary to the script he and Turing did not work together.

As biographer Hodges “has said it is ‘ludicrous’ to imagine that two people working separately at Bletchley would even have met. Security was far too tight to allow it. Creative license is one thing, but slandering a great man’s reputation – while buying into the nasty 1950s prejudice that gay men automatically constituted a security risk – is quite another. For its appalling suggestion that Alan Turing might have covered up for a Soviet spy, it must be sent straight to the bottom of the class.” – The Guardian.

Just two examples of the kind of rot that permeates countless articles.