On July 16, 1991, black gay men across the country saw their lives represented on television thanks to the ground-breaking work of filmmaker Marlon Riggs.

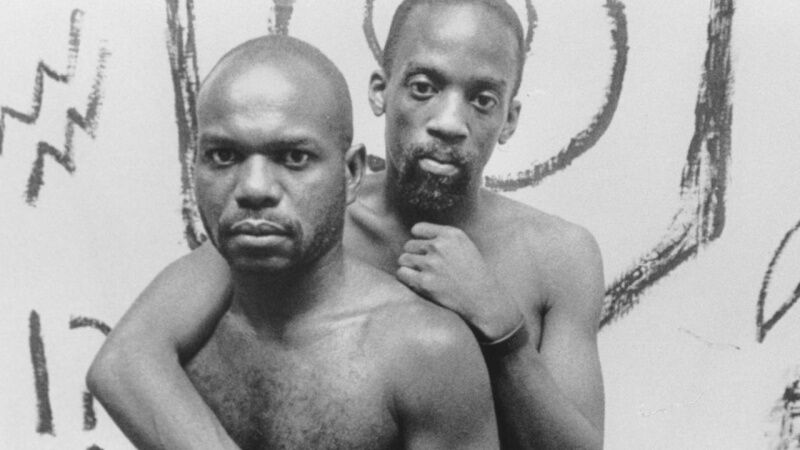

That was the day that the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) aired Riggs’ film Tongues Untied as part of its “P.O.V.” documentary series. Graphic and controversial, Riggs’ free-form film about black men loving black men was unlike anything previously seen on American television.

Born to a military family in Fort Worth, Texas, on February 3, 1957, Riggs spent his childhood at military posts from Georgia to Germany. Later in life, Riggs would recall in his film work the bullying and name calling he experienced at Hephzibah Junior High School in Hephzibah, Georgia, where both black and white students called him a “punk,” a “faggot,” and an “Uncle Tom.”

He would later say, “I was caught between these two worlds where the whites hated me, and the blacks disparaged me.”

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

In 1978, Riggs graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University with an undergraduate degree in history. It was during his time at Harvard that Riggs realized he was gay.

He petitioned the history department and received permission to pursue an independent study of “male homosexuality in American fiction and poetry.” As he studied the history of racism and homophobia in America, Riggs became interested in addressing these subjects in film.

Riggs worked for a Texas television station before moving to Oakland, California, where he lived for 15 years with his life partner Jack Vincent. Riggs attended graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, and earned a masters degree in journalism with a specialization in documentary film. After graduate school, Riggs worked on independent documentary film productions in the Bay Area.

In 1987, Riggs became a part-time faculty member at the Graduate School of Journalism at Berkeley, teaching documentary filmmaking. The same year, he released his first documentary, Ethnic Notions, which explored stereotyped images of black people in American popular culture, and for which Riggs received an Emmy Award.

The film remains relevant in the current political/cultural climate, with its controversies over Virginia’s governor and the implications of white people wearing blackface.

Riggs continued teaching at Berkeley and kept making films. In 1998, while working on his next documentary, Riggs was diagnosed with HIV after receiving treatment for an unrelated kidney problem at a hospital in Germany.

In 1989, Riggs releasedTongues Untied, his poetic and deeply personal documentary exploring the black gay experience through monologues, songs, dramatic performance, and autobiographical footage. Airing as part of PBS’ “P.O.V.” documentary series, it was the first frank representation of the black gay experience on American television.

Acclaimed by critics, the film was awarded Best Documentary at the Berlin and other film festivals. Right-wing organizations like Focus on the Family and the American Family Association attacked the documentary because of its graphic content and because Riggs received a $5,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Conservatives used the film to attack funding for PBS and the NEA, both of which defended the film. Local television stations were not necessarily as bold. Over 100 PBS affiliates declined to show it, while many that chose to air it did so with prominent and frequent disclaimers.

Riggs would go on to produce more documentaries. Color Adjustment, which examined the portrayals of African-Americans in prime time television, received television’s Peabody Award in 1991. The same year Riggs was received the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

In 1994, Riggs began working on Black Is … Black Ain’t, which takes on the subjects of African-American identity, skin color, politics, class, religion, and sexuality. It would be his last film. Several months into the documentary, Riggs became critically ill and was hospitalized.

Riggs would not live to finish his final project.Black Is … Black Ain’t would be completed posthumously by his co-producer. Riggs succumbed to complications from AIDS on April 5, 1994, survived by his partner Jack Vincent, his parents Jean and Alvin Riggs, and his sister, Sascha.