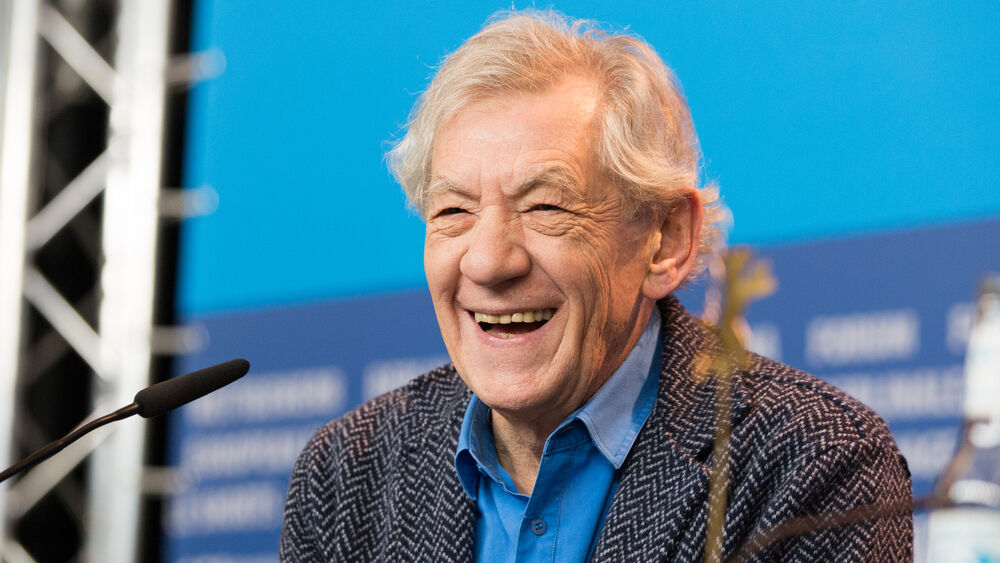

Ian McKellen, the openly gay, 79-year-old British actor best known for playing Gandalf in Lord of the Rings and Magneto in the original X-Men film trilogy, recently sat down for a #QueerAF podcast with BBC journalist Evan Davis in front of the students of Westminster University in Marylebone, England in celebration of National Student Pride 2019.

During their chat, they discussed McKellen’s personal coming out journey, the rumor that he once told two children of an anti-gay politician to ‘F*ck off’ (he didn’t), being an early member of the U.K. gay rights organization Stonewall U.K., chemsex, and other topics.

Here are some highlights from their chat:

On being a gay young person during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s:

Looking back, there was silence. Absolute silence. If you began to think as I did that I was attracted to men and people of my own age, there was no one, absolutely no one to talk to about it. There was nothing that I knew of to read. There were no gay publications. There were not in Bolton, there may not be today. And no gay social places where you could reliably meet people.

The only indication that you got that you were not alone were the rather nasty drawings of genetalia in the public lavatories with telephone numbers or ‘Meet me here at 7:30.’ Ummm… (checking his watch) but you couldn’t be sure what day they were talking about.

There was nothing of course at school, nothing of course in church, nothing of course at my home, though I think I had a gay cousin, but he was married, so that was just a … There was nothing…. And being silent, I didn’t speak. I wasn’t a rebel at all, I just thought, ‘Well, this is the way I am, but I don’t know what to do about it.’ So I didn’t do anything about it.

It took me until my third year at university to have anything I could call proper sex, and even then the world didn’t really change because I didn’t tell anybody about it.

On how the press never used to discuss actors’ homosexuality:

And seriously, one of the reasons I became a professional actor was that I’d heard that you could meet queers in the British theatre. And my dears, it’s quite true that you can. And so, in my first week of being a professional actor, I became far more open and I fell for a much older man in the company of actors in Coventry. I was 22, and he was very nearly 27. But even after that, for another couple of decades, gay liberation passed me by. It wasn’t a proselytizing organization.

And even being in Bent, Martin Sherman’s sensational play which educated the world about the ill treatment of gay people under the Third Reich in the labor camps, I was saying to the press, ‘Oh, this is not a play about gay rights, it’s about human rights.’ Well of course it is, but it also is not.

And I didn’t get any pressure from anybody to say ‘Come out and be yourself,’ because I was being quite happily, living quite openly with a history teacher in our flat. We had gay friends, straight friends, we went out together, always as a couple, Bryan and I. But of course, we never held hands.

“It was kind of don’t ask, don’t tell,” the interviewer interjects. McKellen responds:

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Yeah, but nobody was asking, not even the press interviewing a man in his late 30s who wasn’t married. They didn’t say, ‘Are you looking, are you hoping to get married one day? Have you got a girlfriend?’ Those questions were not asked because it was the worst thing you could possibly say about somebody in print, that they were gay.

And Simon Callow, there should be a statue to Simon Callow, he was the first, as far as I know, openly gay actor in this country because he had grown up gay, he was gay at university, and when he became an actor, he was gay too.

And he talked about it in the press and the press would not report it. They didn’t mention it because they thought he didn’t know what was good for him. And so he had to write a book to come out. You see? Strange, strange days.

On his political awakening during the 1980s:

Davis says, “So you did come out and it was around the time of Section 28, and it was late ‘80s, the Thatcher government takes this measure—now very very widely seen as a terrible terrible piece of legislation—that effectively banned the promotion of homosexuality, but was singling out a particular group in a piece of legislation, and that was kind of your political awakening.”

McKellen responds:

A lesbian friend of mine gave me some information about Section 28 which I was ignorant of, and I immeidtaley wanted to join in the fight that had started. And I found it very easy to be indignant and to awaken something in myself that should’ve been stirred up years before.

And in the course of a radio interview about Section 28 with one Peregrin Worsthorn… rather right-wing—I think he was the editor of the Daily Telegraph and the time—and he was [pro-]Section 28, though it was on record that he’d had sex with [a boy] at school, so I don’t know what the problem was: he obviously had an easier time of it than I had.

Anyway, we argued on the radio and eventually, I said, ‘Oh, will you stop talking about ‘them’? You’re talking about me.’ And I think I said, ‘I’m homosexual.’ I hadn’t quite come around to using the word ‘gay.’ ‘Queer’ was not a word we liked to use about ourselves because it was a word that was used about us. We hadn’t realized that we could grab that word and keep it for ourselves.

On coming out to his older step-mother:

And the first thing I did before the broadcast went out two days later was to go up to see my 80-year-old stepmother and tell her that I was gay at 48. And I was shaking and shivering and stammering. And when I eventually said, ‘Gladys, I’m trying to tell you that I’m gay,’ she said, ‘Oh darling, I thought you were gonna tell me something really dreadful. I’ve known that for 35 years.’ (laughs)

On the rumor that he once told an antigay politician’s kids to ‘F*ck off’:

I got involved with over 20 openly gay or lesbian people who started a lobbying group which still exists, Stonewall, and on their behalf. And being a bit famous, they were rather flattered with the idea that I might, as I did on a Sunday morning, go to [State Secretary] Michael Howard’s house where I met his charming wife and two daughters, and I tried to persuade him that he was wrong, and I didn’t succeed.

And we had a little moment, a pleasant disagreement. And so feeling a bit disconsolate, I was shown the door, but not before he said, ‘Would you mind signing my children’s autograph albums?’ I said, ‘Are you sure they’ll want a gay man in their—?’ ‘Oh yes, they’re fine.’ And I am supposed to have put in these autograph albums, ‘F*ck off,’ but of course I didn’t.

Y’know, Michael Howard has now apologized. Oh good for him, well done. Now he has said he regrets the stance he took, but he was doing it at the bidding of Margaret Thatcher who, although she worked happily with gay people professionally, she didn’t really understand that there was a need for them to join the human race.

On being one of the gay rights movement’s less confrontational advocates:

The interviewer then asked McKellen about his political activism with Stonewall U.K., stating that McKellen was one of the group’s more peaceful early members, comparing his meeting with politicians to its agitating direct-action activists who’d publicly protest, interrupt religious figures’ sermons and such.

Mc Kellen says:

Peter [Tatchell, current leader of Stonewall] has no bigger fan than me. At the time, he didn’t really approve of what Stonewall was. We weren’t a democratic organization. We didn’t have membership. We were a lobby group, we were self-appointed and we thought the argument was pretty clear that we wanted all the anti-gay laws to be repealed… and yes, I think it’s been achieved in the U.K.

And Peter I think wanted to change the world. He thought that being queer made one different and there was a different view of society to be imagined and that was something to be fought for in any way possible.

We just went in our best suits in the offices and made the case. Actually what happened without us realizing it was that the government, the establishment thought that they were being protected from Peter and the likes who could potentially be violent, I think was their fear, because we were so respectable. It was a very good partnership.

“It was good cop, bad cop game, really,” the interviewer says. McKellen replies:

I think that’s still true today, that you don’t have to be in the big organization to make it happen. There can be lots of organizations.

The idea that there’s such a thing as the ‘gay community,’ I’ve never fallen for at all. We’re not a community. There’s lots of communities… and it’s very difficult to think that we’re all the same in our desires and everything else.

On why LGBTQ rights have moved more quickly in the U.K. than in the U.S.:

The interviewer then says that there’s so much to keep up with in the global struggle for LGBTQ rights, and McKellen admits:

I don’t keep up, I just get on with my life being me. That’s all I’ve ever done. I’ve never been the leader, I’ve carried the flag, but I didn’t design it, you know. So I’m just one of the troops, really.

I saw Peter on the streaming earlier today saying that in the old days, it was not equality that we were after, but that always was Stonewall’s aim. We should be treated equally under the law and that has really been achieved.

It’s been achieved in this country I think because we’re a small country. Y’know, if you want change, it’s all going to happen in this city and you can bump into people. It is possible to meet the person who will make the decision at some gathering or other in a way that’s just absolutely not possible in the United States for example, which is just a continent. We’re a small country and I think that’s been a great benefit to us.

On his advice to younger queer people:

Well my best friend at school, David Hargreaves, we went to the theater together. We did high kicks in the playground, we acted together, we were inseparable and we were both gay, and I didn’t know that about David until 25 years later. You see, this silence?

What I love about schools is that it is possible to think of school as the world. Within those walls you can make a society and it seems to me—whether they’re private schools or public schools, whether they’re academies or grammar schools—that the aim seems to be the same from the teachers to create within that a safe place where whatever’s happening at home, whatever’s happening on the streets, whatever’s happening in the public debate, at school you are safe to be yourself and that goes for transgender kids too.

And so far from giving them advice, I get a bit weepy and think, ‘Oh, it should’ve been like this when I was in school.’ Because of course, if you can be yourself, if you can express yourself, if you can puzzle about yourself, if you can argue and worry and try to understand yourself you’re going to better at your studies aren’t you, you’re gong to be better as a child at home, you’re going to be better as a lover, you’re going to be better in every possible way. (Singing from La Cage Aux Folles) ‘I am what I am!’ And what is am? What are you? I don’t know.

At one school I was at recently, there was a little group that I was allowed to talk to after I had addressed the group, and these were people with particular problems. And opposite me there was a tough little boy named Finn who six months before had been a tough little girl named Finn… Then there was George… he was 15. And he said, ‘What do you do if your daddy is gay and your mummy tells you this morning that she is too.’ I said, ‘It’ll be alright George. It’ll sort itself out.’ But he said that, he’d come out with his problem and the teacher said, ‘Terrific, well done. We’ll talk about that whenever you want.’

And here there were three gals. It wasn’t a school that had uniforms. They looked sensational, these girls. It looked as if they were just going out for the night, but it was mid-morning. And one of them said, ‘Look, I’m talking with these two here, and we’re bi… If we’re having an affair with a boy at the moment, well presumably we’re straight at the moment, and then if we have a girlfriend, then presumably we’re lesbian. We’re fed up with these labels.’

And I saw a light went on. I thought, ‘Well that’s the future: no labels. No flags. I am what I am.’ And if we could just get that into our heads, that we accept someone regardless of what they look like or where they were born or what their accent is or what their sexuality might be or is going to be, then what an interesting world the place will be.

Variety is the spice of life. The idea that we’re all the same is so dull. And of course were not, and if I could see your faces now, we wouldn’t be able to find two people who looked alike, unless they were twins. And no offense to twins.

On modern-day drug use, chemsex and people dying from overdosing:

Well, I had my first joint when I was 30, so I wasn’t part of the ‘60s at all…. Look after your health, number one. I’m surprised anyone of student age would need the extra thrill of drugs to make the sex satisfactory. I’d think that was more for people of my age.

On being one of the few older gay role models who survived the HIV epidemic:

I just get on with my life. I’m single, but actually there are other people living in the house…. But it’s not a gay commune actually. Well, one bisexual, one guy who doesn’t realize he’s gay (laughs), they’re all men at the moment. No, I feel… I just wish when I was younger I could’ve been myself because I’d be different now…

That virus which killed so many friends, without it there would not have been the great surge of success that gay people have had in defending themselves because the Thatcher government that tried to put us down with Section 28 and keep us ignorant… that government sent round a pamphlet to every household in the country warning them about the dangers of unprotected sex. They didn’t approve of unprotected sex, but they had to tell us about it because it was an important national health issue.

And that’s the time the newspapers began to talk about the idea that two men or two women together could be very happy having sex. So out of that dreadful, dreadful virus, came the hope and the change which we have now.

On his thoughts on Bryan Singer, Kevin Spacey and the #MeToo movement:

Well frankly, I’m waiting for someone to accuse me of something, and me wondering whether they’re not telling the truth and me having forgotten (pointing to his head) you know.

But with the couple of names you’ve mention, people I’ve worked with, both of them were in the closet. And hence all their problems as people and their relationships with other people, if they had been able to be open about themselves and their desires, they wouldn’t have started abusing people in the way they’ve been accused.

Whether they should be forced to stop working. That’s debatable. I rather think that’s up to the public. Do you want to see someone who has been accused of something that you don’t approve of again? If the answer’s no, then you won’t buy a ticket, you won’t turn on the television. But there may be others for who that’s not a consideration.

And it’s difficult to be exactly black and white.